Psychomachia

The Psychomachia (Battle of Spirits or Soul War) is a poem by the Late Antique Latin poet Prudentius, from the early fifth century AD.[1] It has been considered to be the first and most influential "pure" medieval allegory, the first in a long tradition of works as diverse as the Romance of the Rose, Everyman and Piers Plowman; however, a manuscript discovered in 1931 of a speech by the second-century academic skeptic philosopher Favorinus employs psychomachia, suggesting that he may have invented the technique.[2]

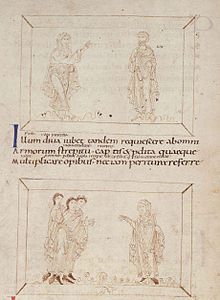

In slightly less than a thousand lines, the poem describes the conflict of vices and virtues as a battle in the style of Virgil's Aeneid. Christian faith is attacked by and defeats pagan idolatry to be cheered by a thousand Christian martyrs. The work was extremely popular, and survives in many medieval manuscripts, 20 of them illustrated.[3] It may be the subject of wall paintings in the churches at Claverley, Shropshire, and at Pyrford, Surrey, both in England. In the early twelfth century it was a common theme for sculptural programmes on façades of churches in western France, such as Aulnay, Charente-Maritime.[4]

The word may be used more generally for the common theme of the "battle between good and evil", for example in sculpture. The duality portrayed in the book was the first of its kind to depict the different moral realms humans are battling within themselves. It was the first time one got to read how all are participating in the war of the soul, because Vice and Virtue both live within them and their decisions and actions determine the outcome of the conflict.

Characters

[edit]The plot consists of the personified virtues of Hope, Sobriety, Chastity, Humility, etc. fighting the personified vices of Pride, Wrath, Paganism, Avarice, etc. The personifications are women because in Latin, words for abstract concepts have feminine grammatical gender; an uninformed reader of the work might take the story literally as a tale of many angry women fighting one another, because Prudentius provides no context or explanation of the allegory.[5]

- Faith (Fides) strikes Worship-of-the-Old-Gods Idolatry (Veterum Cultura Deorum) on the head.

- Chastity (Pudicitia) is assaulted by Lust (Sodomita Libido), but cuts down her enemy with a sword.

- Patience (Patientia) enrages Wrath (Ira), who attacks but cannot defeat or even injure her. Driven mad with frustration, Anger ultimately kills herself instead.

- Humility (Mens Humilis) otherwise known as Lowliness, sees Pride (Superbia) charging her, but her horse stumbles, and Pride is thrown in a pit that Deceit has already dug across the field.

- Sobriety (Sobrietas) plants her flag and restores the courage that was taken from the other virtues by the temptation of Indulgence (Luxuria).

- Good Works (Operatio) strangles Greed (Avaritia) who has seized the entire human race.

- Concordia, having heard such great blasphemy, pins the tongue of Discordia with a spear and stops her breath.

In a similar manner, various vices fight corresponding virtues and are always defeated. Biblical figures that exemplify these virtues also appear (e.g. Job as an example of patience).

Despite the fact that seven virtues defeat seven vices, they are not the canonical seven deadly sins, nor the three theological and four cardinal virtues.

Notable manuscripts

[edit]

- Berne, Burgerbibliothek Cod. 264, region of Lake Constance c. AD 900. Parchment, 145 foll., 27.3/28.3 x 21.5/22 cm. The ms. is counted among the outstanding examples of Carolingian book art. It contains all seven poems by Prudentius plus an added eighth poem; given to the Strasbourg diocese in the 990s and later was acquired by Jacques Bongars.[6]

- Cambridge, Corpus Christi College, MS 23; Prudentius, Psychomachia and other poems, 10th century, English.[7]

- London, British Library, Add MS 24199, part 1; Miscellany (Prudentius, Psychomachia), 10th century.

- MS Cotton Cleopatra C VIII; Prudentius, Psychomachia, 10th century.

- Munich, Staatsbibliothek, CLM. 29031b; Prudentius, Psychomachia, 10th century.

Other uses of 'psychomachia'

[edit]Theatre historian, Jonas Barish uses the term psychomachia to describe anti-theatrical conflict during the nineteenth century.[8]

Kirsty Allison used Psychomachia as the title for her cult novel, set in the 1990s (Wrecking Ball Press, 2020). The first edition also publishes a translation, and a modernised edit was later published in LoveLove magazine.

Notes

[edit]- ^ Holcomb

- ^ Heinz-Günther Nesselrath, "Later Greek Voices on the Predicament of Exile: from Teles to Plutarch and Favorinus", in: J. F. Gaertner (Ed.), Writing Exile: The Discourse of Displacement in Greco-Roman Antiquity and Beyond, Leiden 2007 ISBN 9004155155 p 104

- ^ Holcomb, 69–71

- ^ Anat Tcherikover: High Romanesque Sculpture in the Duchy of Aquitaine c.1090-1140, 148-151. Clarendon Press, Oxford 1997 ISBN 0-19-817410-1.

- ^ William R. Cook and Ronald B. Herzman (2001). Discovering the Middle Ages. The Teaching Company. ISBN 1-56585-701-1

- ^ Burgerbibliothek Cod. 264 (e-codices.unifr.ch)

- ^ Holcomb, 69–71

- ^ See Antitheatricality § 19th and early 20th century (psychomachia).

References

[edit]- Holcomb, M. (2009). Pen and Parchment : Drawing in the Middle Ages. New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art. p. 69. MS 23, Corpus Christi College, Cambridge

- Magnus Frisch: Psychomachia. Einleitung, Text, Übersetzung und Kommentar (= Texte und Kommentare. Bd. 62). De Gruyter, Berlin/Boston 2020, ISBN 3-11-062843-0.

External links

[edit]- The Latin original of the poem

- Several medieval illustrations of the battle scenes described

- Psychomachia (translated to English)

- Psycomachia Vices folio 200v of manuscript Hortus Deliciarum ca. 1170 CE, Strasbourg (online catalog Oberlin College)

- Psycomachia Virtues folio 201r of manuscript Hortus Deliciarum ca. 1170 CE, Strasbourg (online catalog Oberlin College)

- British Library manuscript 24199 record and images