Kohala (mountain)

| Kohala | |

|---|---|

Kohala volcano as seen from Mauna Kea | |

| Highest point | |

| Elevation | 5,480 ft (1,670 m)[1] |

| Prominence | 2,600 ft (790 m)[2] |

| Coordinates | 20°05′10″N 155°43′02″W / 20.08611°N 155.71722°W[1] |

| Naming | |

| Language of name | Hawaiian |

| Pronunciation | Hawaiian pronunciation: [koˈhɐlə] |

| Geography | |

Hawaii, U.S. | |

| Parent range | Hawaiian Islands |

| Topo map | USGS Kamuela |

| Geology | |

| Age of rock | >1,000,000 years |

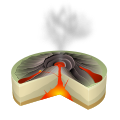

| Mountain type | Shield volcano, Hotspot volcano[1] |

| Volcanic arc/belt | Hawaiian-Emperor seamount chain |

| Last eruption | About 120,000 years ago[1] |

Kohala is the oldest of five volcanoes that make up the island of Hawaii. Kohala is an estimated one million years old—so old that it experienced, and recorded, the reversal of Earth's magnetic field 780,000 years ago. It is believed to have breached sea level more than 500,000 years ago[1] and to have last erupted 120,000 years ago. Kohala is 606 km2 (234 sq mi) in area and 14,000 km3 (3,400 cu mi) in volume, and thus constitutes just under 6% of the island of Hawaii.[1]

Kohala is a shield volcano cut by multiple deep gorges, which are the product of thousands of years of erosion. Unlike the typical symmetry of other Hawaiian volcanoes, Kohala is shaped like a foot. Toward the end of its shield-building stage 250,000 to 300,000 years ago, a landslide destroyed the northeast flank of the volcano, reducing its height by over 1,000 m (3,300 ft) and traveling 130 km (81 mi) across the sea floor. This huge landslide may be partially responsible for the volcano's foot-like shape.[3] Marine fossils have been found on the flank of the volcano, far too high to have been deposited by standard ocean waves. Analysis indicated that the fossils had been deposited by a massive tsunami approximately 120,000 years ago.

Because it is so far from the nearest major landmass, the ecosystem of Kohala has experienced geographic isolation, resulting in a unique ecosystem. There are several initiatives to preserve this ecosystem against invasive species. [citation needed] Crops, especially sweet potato (Ipomoea batatas), have been cultivated on the Leeward side of the volcano for centuries. The northern part of the island is named after the mountain, with two districts named North and South Kohala. King Kamehameha I, the first King of the Kingdom of Hawaii, was born in North Kohala, near Hawi.

Geology

[edit]History

[edit]

Studies of the volcano's lava accumulation rate have put the volcano's age at somewhere near one million years.[3] It is believed to have breached sea level more than 500,000 years ago. Beginning 300,000 years ago, the rate of eruption slowly decreased over a long period of time to a point where erosion wore the volcano down faster than Kohala rebuilt itself through volcanic activity. Decreasing eruptions combined with increasing erosion caused Kohala to slowly weather away and subside into the ocean. The oldest lava flows that are still exposed at the surface are just under 780,000 years old. It is difficult to determine the original size and shape of the volcano, as the southeast flank has been buried by volcanic lava flows from nearby Mauna Kea and Mauna Loa.[1][4] However, based on a sharp increase of incline on the submarine slope of the volcano at a depth of 1,000 m (3,300 ft), scientists estimate that in its prime the portion of Kohala that was above the water was more than 50 km (31 mi) wide.[1] Geologists estimate that the volcano was once about twice its current size.

The volcano is so old that it experienced, and recorded, a reversal of magnetic polarity (a change in the orientation of Earth's magnetic field so that the positions of the North and South poles interchange) that happened 780,000 years ago. Fifty flow units in the top 140 m (460 ft) of exposed strata in the Pololu section are of normal polarity, indicating that they were deposited within the last 780,000 years. Radiometric dating ranged mostly from 450,000 to 320,000 years ago, although several pieces strayed lower; this indicated a period of eruptive history at the time.[3]

Kohala was devastated by a massive landslide between 250,000 and 300,000 years before present. Debris from the slide was found on the ocean floor up to 130 km (81 mi) away from the volcano. Twenty kilometers wide at the shoreline, the landslide cut back to the summit of the volcano, and is partially, if not largely, responsible for the volcano losing 1,000 m (3,300 ft) in height since then. The famous sea cliffs of the windward Kohala shoreline stand as evidence of the massive geologic disaster, and mark the topmost part of the debris from this ancient landslide.[1] There are also several other unique features found on the volcano, all marks made by the decimating collapse.[3]

Kohala is thought to have last erupted 120,000 years ago. However, several samples of a more recent date have been obtained. Two samples collected about 120 m (390 ft) apart, obtained from Waipiʻo Valley on the volcano's east flank in 1977, were dated reliably to 60,000 years. Another double set of samples, collected from the western part in 1996, was measured to be 80,000 years in age. The samples have been treated with skepticism by the scientific community, and their ages have been directly challenged. The rocks collected from the west site have not been tested by subsequent experiments. The lava samples collected from the eastern site were allegedly found under a Mauna Loa lava flow, which had been previously dated to 187,000 years. The Kohala lava flows could be as young as 120,000 years although they may be even younger.[3]

In 2004, unidentified marine fossils were found at the base of the volcano 6 km (3.7 mi) inshore. A research team led by University of Hawaii's Gary McMurtry and Dave Tappin of the British Geological Survey found that the fossils had been deposited by a massive tsunami, 61 m (200 ft) above the current sea level.[5] The team dated the fossils and nearby volcanic rock at about 120,000 years old. Based on the rate of Kohala's subsidence over the past 475,000 years, it was estimated that the fossils were deposited at a height of about 500 m (1,600 ft), well out of reach of storms and far above the normal sea level at the time.[6] The timing corresponds with the last great landslide of nearby Mauna Loa. Researchers hypothesize that the underwater landslide from the nearby volcano triggered a gigantic tsunami, which swept up coral and other small marine organisms, depositing them on the western face of Kohala. Mauna Loa, an active volcano, has since repaired its flank. Marine geologist Tappin believes that a "future collapse on this volcano, with the potential for mega-tsunami generation, is almost certain."[6]

Structure

[edit]Kohala had two active rift zones, a characteristic common to Hawaiian volcanoes.[3][7] The double ridge, shaped axially, was active in both the shield and postshield stages. The southeast rift zone passes under the nearby Mauna Kea and reappears further southeast in the Hilo Ridge, as indicated by the relationship between collected lava samples. In addition, the two features align to one another more closely than does the ridge to Mauna Kea, of which it was once thought to constitute a part. The bulk of the ridge is built of volcanic rock with reverse magnetic polarity, evidence that the volcano is at least 780,000 years old. Older lava dated from the toe of the ridge was estimated to be roughly between 1.1 and 1.2 million years old.[3]

Geologists have classified the volcano's lava flows into two units. The Hawi Volcanic layers were deposited in the postshield stage of the volcano's life, and the younger Pololu Volcanics were deposited in the volcano's shield-building stage. The rock in the younger Hawi section, which overlies the older Pololu flows, is mostly 260,000 to 140,000 years old, and composed mainly of hawaiite and trachyte. The separation between the two layers is not clear; the lowest layers may actually be in the Pololu section, based on their depositional patterns and low phosphorus content. The time intervals separating the two periods of volcanic evolution were extremely brief, something first noted in 1988.[3]

The forest-covered summit of the volcano consists of many cones which generated lava from its two rift zones between 240,000 and 120,000 years ago.[1] Kohala completed its shield-building stage 245,000 years ago and has been in decline ever since.[8] Potassium-argon dating indicates that the volcano last erupted about 120,000 years ago in the late Pleistocene.[1][9] Kohala is currently in transition between the postshield and erosional Hawaiian volcanic stages in the life cycle of Hawaiian volcanoes.[5]

The United States Geological Survey has assessed the extinct Kohala as a low-risk area. The volcano is in zone 9 (bottom risk), while the border of the volcano with Mauna Kea is zone 8 (second lowest), as Mauna Kea has not produced lava flows for 4,500 years.[10]

Kohala, like other shield volcanoes, has a shallow surface slope due to the low viscosity of the lava flows that formed it; however, the northwest shoreline boasts some of the highest seacliffs on Earth. Events during and after its eruptions give the volcano several unique geomorphic features, some possibly resulting from the ancient collapse and landslide. The volcano is shaped like a foot; the northeast coast is prominently indented across 20 km (12 mi) of shoreline.[3]

There is a small string of faults on and near the main summit caldera, arranged parallel to the northern coast. The faults were originally regarded to be a direct result of the collapse; however scientists note the fault lines do not go all the way to the coast but are arranged tightly clustered around the caldera. This indicates that the fault lines may have been caused indirectly, possibly due to the sudden release of stress during the event.[3]

Hydrology

[edit]

Mauna Kea causes the trade winds to divert around it, increasing wind to super-enhanced flow over the Kohala ridge[11] and orographic lift brings most of the rainfall to the northeastern slope of Kohala.[12] The windward side of Kohala mountain is dissected by multiple, deeply eroded stream valleys in a southwest–northeast alignment, cutting into the flanks of the volcano. North of Kohala's summit the volcano's northwest–southeast trending rift zone separates rainfall into two streams, going southeast, into Waipiʻo Valley, or northwest, into Honokane Nui Valley. When the volcano was still active, vertical sheets of magma, arranged in what is known as dikes, forced their way out of the magma reservoir and intruded into the rift zone, which was weakened by the collapse.[3][13] As the dikes forced their way up, they formed fractures and faults parallel to the rift zone. The exertion caused by the dikes produced a series of faults along its length, forming horsts and grabens (fault blocks). Northeast of the Kohala summit, where the most rainfall occurs, the faulted structure prevents summit rainwater from naturally flowing northeast down the mountain slope. Instead, the rainwater flows down laterally and empties into the back of what have thus become the largest valleys (Waipiʻo and Honokane Nui).[13]

The leeward northwestern slope of Kohala has few stream valleys cut into it, the result of the rain shadow effect, as the dominant trade winds bring most of the rainfall to the northeastern slope of the volcano. The seven windward valleys of Kohala are, from southeast to northwest, Waipiʻo, Waimanu, Honopue, Honokea, Honokane Iki, Honokane Nui, and Pololu.[12] The size of the valleys reflects the amount of drainage they have been able to capture; Waipiʻo, the largest, at some point drained Waimanu Valley as well, and the former headwaters of Waimanu are now one of its branches.[14] Waimanu valley, cut off from its headwaters to the summit and left with Wai'ilikahi as its main tributary, still had managed to form a substantial floodplain, although less than half the size of Waipiʻo. Honokane Nui, the third largest valley, has its drainage almost exclusively from the north side of the summit, and as a result is a deep, long, narrow bottomed valley with little habitable floodplain.[15][16]

The remaining valleys derive all their water from the lower northeastern slopes of the volcano, and as a result are smaller. In addition, there are innumerable gulches of various depths which have not yet reached sea level and began to form flood plains, becoming valleys. Still, some of these are more than 300 m (1,000 ft) in depth.[17] The depth of the actual valley walls at the seashore range from 300 m (1,000 ft) at the Waipiʻo Valley Lookout at the southeastern corner of Kohala mountain, to a high of over 500 m (1,600 ft) in Honopue, then diminishing to less than 150 m (490 ft) at Pololu Lookout at the northern end of the valleys. In the back, deeper in the mountain, all of the valleys have sheer walls well in excess of 1,000 m (3,300 ft). Numerous spectacular waterfalls cascade or fall over these cliffs. Some, such as Hi'ilawe Falls in Waipi'o valley, have single drops exceeding 300 m (1,000 ft).

The volcano stayed active well into the formation of these mountainside valleys, as illustrated by later Pololu lava flows, which covered the north and northwestern end of Kohala volcano and often flowed into Pololu Valley. Recent seafloor mapping seems to show that the valley extends a short way beyond the seashore, then terminates at what may be the headwall of the great landslide found off the northeast coast of Kohala.[3]

In addition to being a primary factor in the development of the largest valleys, the dike complex plays another important role —that of creating and maintaining the water table. Hawaiian lava is extremely permeable and porous. Rainwater easily seeps into the lava, creating a large lens of fresh water below the island surface. In most places, the top of the water table is just a few feet from sea level, as the fresh water lens is floating on salt water. Unlike porous lava flows, however, dikes cool underground into dense rock with few cracks and vesicles. The dikes act as impermeable vertical walls through which groundwater cannot flow. Deep layers of ash compact into impermeable layers between lava flows, preventing percolation of the rainwater. Rainwater that would ordinarily seep right through the ground gets trapped in the dike "reservoirs," located well above sea level. The groundwater is confined to a flow along the dike until it finds a means to escape.[13]

In Kohala, the numerous dikes near the summit inhibit groundwater from seeping downslope to the northeast, where it naturally wants to go. Rather, the Kohala dike complex guides it northwest or southeast, down the axis of the rift zones, just like the surface water. On the other hand, the three smaller valleys between the large ones - Honopue, Honokea, and Honokane Iki - as well as the many smaller gulches which are not yet valleys, are deprived of groundwater by the orientation of the rift zone and its dikes. Without the large amount of water that is received by the bigger valleys, these valleys grow far more slowly. Due to its topography as essentially a flat crater floor surrounded by cones and fault scarps, the main caldera is affected relatively little by erosion from water.[13]

Most of Kohala's summit groundwater ends up in either Waipi'o or Honokane Nui; the enormous amount of water routed through these valleys results in a large amount of water erosion, which causes the valley walls to frequently collapse, accelerating valley development.[13] This abundance of surface water inspired the first of Kohala's three massive irrigation diversion "ditches", the Upper Hamakua Ditch, although the water was initially used for transporting ("fluming") sugarcane to the mills rather than irrigation. Surface water supplies, however, were not stable enough for the large scale plantation economy developing in Hamakua and North Kohala, so later ditches tapped the spring fed base flows of the valleys and larger gulches. Only Waimanu Valley escaped with none of its tributaries tapped, along with the 16 smaller streams between Waikoloa Stream and the Wailoa river in Waipi'o Valley.[18]

Ecology

[edit]

The natural habitats in the Kohala district range across a wide rainfall gradient in a very short distance—from less than 5 in (130 mm) a year on the coast near Kawaihae, to more than 150 in (3,800 mm) a year near the summit of Kohala Mountain, a distance of just 11 mi (18 km). At the coast are remnants of dry forests, and near the summit lies a cloud forest, a type of rainforest that obtains much of its moisture from "cloud drip" in addition to precipitation.[19] These large cloud forests dominate its slopes. This biome is rare, and contains a disproportionate percentage of the world's rare and endemic species.[20] The soil at Kohala is nitrogen-rich, facilitating root growth.[21]

The happy combination of small trees, bushes, ferns, vines, and other forms of ground cover keep the soil porous and allow the water to percolate more easily into underground channels. The foliage of the trees breaks the force of rain and prevents the impact of soil by raindrops. A considerable portion of the precipitation is let down to the ground slowly by this three-story cover of trees, bushes, and floor plants and in this manner the rain, falling on a well-forested area, is held back and instead of rushing down to the sea rapidly in the form of destructive floods, is fed gradually to the springs and to the underground artesian basins where it is held for use over a much longer interval...[15]

C S Judd, Superintendent of Forestry in Hawaiʻi, 1924

The forest lies perpendicular to the prevailing trade winds, a characteristic that leads to frequent cloud formation and abundant rainfall. Thus the rain forests carpeting Kohala are vital to the supply of groundwater on the island. The role of Kohala's ecosystem in supporting water flow has long been recognized. As early as 1902, US Forester E. M. Griffith wrote "Forest protection means not only increasing the rainfall, but more important still, conserving the water supply. The future welfare and agricultural prosperity of the Hawaiian Islands depends upon the preservation of the forest."[15]

Before humans arrived, the wildlife population at Kohala and on the rest of the island was isolated from other species, as it was separated from the nearest major landmass by over 2,000 mi (3,200 km) of open water. The early colonizers of Kohala came by wind, storm or floating on the ocean. Successful colonizations occur on the magnitude of once every 35,000 years. The 2,000 successful ancestors that arrived at Kohala evolved into about 8,500 to 12,500 unique species, resulting in a very high ratio of the species present being found nowhere else on Earth. Only about 2.5% of the world's rainforest is cloud rainforest, making it a unique habitat as well.[15]

The mountain supports approximately 155 native species of vertebrates, crustaceans, mollusks, and plants. A diverse complexion of fungi, liverwort, and mosses further add to the variety. In fact, up to a quarter of the plants in the forest are mosses and ferns. These work to capture the water from clouds, in turn providing microhabitats for invertebrates and amphibians, and their predators. Estimates on the water capacity of the forest range from 320 to 1,600 US gal/acre (3,000 to 15,000 L/ha).[15]

The mountain is also home to several bogs, which exist as breaks in the cloud forests. It is believed that bogs form in low-lying areas where clay in the soil prevents proper water drainage, resulting in an accumulation of water that impedes the root systems of woody plants. Kohala's bogs are characterized by sedges, mosses of the genus Sphagnum, and oha wai, native members of the bellflower family. Other habitats include rain forest and mesophytic (wet) forests.[15]

The same isolation that produced Kohala's unique ecosystem also makes it very vulnerable to invasive species. Alien plants and feral animals are among the greatest threats to the local ecology. Plants like the kahili ginger (Hedychium gardnerianum) and the strawberry guava (Psidium cattleinum) displace native species.[20] Prior to human settlement, many major organisms such as conifers and rodents never made it onto the island, so the ecosystem never developed defenses against them, leaving Hawaii vulnerable to damage by hoofed animals, rodents, and predation.[15]

Kohala's native Hawaiian rain forest has a thick layer of ferns and mosses carpeting the floor, which act as sponges, absorbing water from rain and passing much of it through to the groundwater in aquifers below; when feral animals like pigs trample the covering, the forest loses its ability to hold in water effectively, and instead of recharging the aquifer, it results in a severe loss of topsoil, much of which ends up being dumped by streams into the ocean.[20]

Human history

[edit]

There is evidence of pre-modern agriculture on the leeward slopes of Kohala. From 1400 to 1800, the principal crop grown at Kohala was sweet potato (Ipomoea batatas), although there is also evidence of yams (Dioscorea sp.), taro (Colocasia esculenta), bananas (Musa hybrids), sugarcane (Saccharum officinarum), and gourds of the family Cucurbitaceae. The optimal rainfall level for the sweet potato lies between 30 and 50 inches (76–127 cm) per year. A combination of factors makes the rainfall at Kohala variable both from location to location and from year to year. In addition, Kohala is buffeted by strong winds, which are directly correlated to soil erosion; ancient farmers utilized a series of earthen embarkments and stone walls to protect their crops. This technique has been shown to reduce wind by at least 20–30 percent.[22]

In addition to walls, there are a series of stone paths that divided the farmed area into plots of variable size. These structures are unique because although many people used such systems at the time, Kohala has some of the few to survive.[22] The leeward slopes of Kohala were used for sugarcane plantations in the late 19th century. The trip from the fields to the mills and then boats was mechanized by steam locomotive in 1883.[23] Several plantations on the mountain were consolidated into the Kohala Sugar Company by 1937.[23] At the peak of its production, the company had 600 employees, 13,000 acres (20 sq mi) of land, and a capacity of 45,000 t (99,000,000 lb) of raw sugar per year. In 1975 the company finally closed down.[24]

Kohala supports a very complex hydrological cycle. In the early part of the 20th century, this was exploited by building surface irrigational channels designed to capture water at the higher elevations and distribute it to the then-extensive sugarcane industry. In 1905, after 18 months and the loss of 17 lives, the Kohala Ditch, a vast network of flumes and ditches, measuring 22 mi (35 km) in length, was completed.[24] It has since come into use by ranches, farms, and homes.[15] A portion of the ditch became a tourist attraction until it was damaged by the 2006 Kiholo Bay earthquake, centered just southwest of the mountain.[25] The Hawaii County Department of Water Supply relies on streams from Kohala to supply water to the population of the island. With increasing demand, the original surface channels have been supplemented by deep wells designed to channel groundwater for domestic use.[15] In 2003 the Kohala Watershed Partnership was formed, a voluntary group of private land owners and state managers, designed to help manage the Kohala watershed and to protect it from threats, most especially invasive species.[20]

Another project to raise awareness of Kohala's ecosystem is The Kohala Center, an independent, not-for-profit, community-based organization for research and education. It was established as a response to requests by island residents to create an educational and employment opportunity related to Hawaii's natural and cultural significance. The center's mission is "to respectfully engage the Island of Hawaiʻi as an extraordinary and vibrant research and learning laboratory for humanity."[26] The land around Kohala is administered as two districts, North Kohala and South Kohala, of the County of Hawaiʻi. The beaches, parks, golf courses, and resorts in South Kohala are called "the Kohala Coast."[27][28]

King Kamehameha I, the first King of the unified Hawaiian Islands, was born near Upolu Point, the northern tip of Kohala. The site is within Kohala Historical Sites State Monument. The original Kamehameha Statue stands in front of the community center in Kapaʻau, and replicas of the statue are found at Aliʻiōlani Hale in Honolulu, and in Emancipation Hall at the United States Capitol Visitor Center in Washington, D.C.

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k "Kohala - Hawai'i's Oldest Volcano". Hawaiian Volcano Observatory. United States Geological Survey. 1998-03-20. Retrieved 2008-08-22.

- ^ "Kohala, Hawaii". Peakbagger: Kaunu o Kaleioohie. peakbagger.com. Retrieved 17 February 2015.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l David R. Sherrod; John M. Sinton; Sarah E. Watkins; Kelly M. Brunt (2007). "Geological Map of the State of Hawaii" (PDF). USGS Hawaii geology pamphlet. USGS. Retrieved 2009-04-12. pp. 41–43

- ^ "Kohala Volcano, Hawaii-Photo Information". USGS Image. USGS. Retrieved 2009-03-30.

- ^ a b Seach, John. "Kohala Volcano - John Seach". Volcanism reference base. John Seach, volcanologist. Retrieved 2009-03-30.

- ^ a b "Hawaiian tsunami left a gift at foot of volcano". New Scientist (2464): 14. 2004-09-11. Retrieved 2008-12-18.

- ^ Garcia, Michael O.; Caplan-Auerbanch, Jackie; De Carlo, Eric H.; Kurz, M.D.; Becker, N. (2005-09-20), Geology, geochemistry and earthquake history of Lōʻihi Seamount, Hawaiʻi, This is the author's personal version of a paper that was published on 2006-05-16 as "Geochemistry, and Earthquake History of Lōʻihi Seamount, Hawaiʻi's youngest volcano", in - Geochemistry (66) 2:81-108, School of Ocean and Earth Science and Technology, archived from the original (PDF) on 2011-07-18, retrieved 2009-03-20

- ^ Moore, James G.; David A. Clague (November 1992). "Volcano growth and evolution of the island of Hawaii". GSA Bulletin. 104 (11): 1471–1484. Bibcode:1992GSAB..104.1471M. doi:10.1130/0016-7606(1992)104<1471:VGAEOT>2.3.CO;2. Retrieved 2008-12-18.

- ^ McDougall, Ian (December 1969). "Potassium-argon ages on lavas of Kohala volcano, Hawaii". GSA Bulletin. 80 (12): 2597–2600. Bibcode:1969GSAB...80.2597M. doi:10.1130/0016-7606(1969)80[2597:PAOLOK]2.0.CO;2. ISSN 0016-7606.

- ^ "Lava Flow Hazand Zone Maps:Mauna Kea and Kohala". USGS. Archived from the original on 2009-01-29. Retrieved 2009-03-30.

- ^ Elliott, DL; Aspliden, CI; Gower, GL; Holladay, CG; Schwartz, MN (April 1987). "DE-AC06-76RL01830". Pacific Northwest National Laboratory. p. 28.

Areas of super-enhanced flow may exist where there are combined accelerations from large-scale and small-scale terrain influences or between two large-scale features. Such areas of super-enhanced flow, caused by these types of combined accelerations, have been verified in Hawaii. For example, on island of Hawaii , low-level flow that is diverted to the north around Mauna Kea (4200 m) undergoes an additional acceleration as it flows over the Kohala ridge, causing an area of super-enhanced flow along the Kohala ridge.

- ^ a b Thomas W. Giambelluca; Michael A. Nullet; Thomas A. Schroeder (June 1986). "Rainfall Atlas of Hawaiʻi" (PDF). Water Resources Research Center - University of Hawaiʻi at Mānoa. Archived from the original (PDF) on 3 March 2012. Retrieved 27 August 2012.

- ^ a b c d e "Origin of the Big Island's Great Valleys Revealed in Hawaiian chant". USGS weekly feature. USGS. 2006-02-16. Retrieved 2009-04-12.

- ^ Charles Merguerian; Steven Okulewicz (2007). "Hofstra University Geology 280F - Field Trip Guidebook: Geology of Hawaii" (PDF). Hofstra University. Retrieved 27 August 2012.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i "Kohala Mountain Watershed Management Plan DRAFT" (PDF). Kohala Watershed Partnership. December 2007. pp. 9, 18–19, 25–28. Archived from the original (PDF) on 28 September 2010. Retrieved 16 December 2009.

- ^ "Puu O Umi Natural Area Reserve Management Plan" (PDF). Hawai'i Department of Land and Natural Resources. November 1989. Retrieved 27 August 2012.

- ^ Mouginis-Mark, Pete. "Airphotos of Kohala". Photos of Kohala. Virtually Hawaii group, Hawaii Center of Volcanology. Retrieved 2009-03-30.

- ^ Carol Wilcox (January 1998). Sugar water : Hawaii's plantation ditches. Honolulu: University of Hawai'i Press. ISBN 978-0824820442. Retrieved 22 March 2014.

- ^ Gon III, S.M. "Hawaiian High Islands Ecoregion". The Nature Conservancy. Retrieved 2009-05-13.

- ^ a b c d "Working together to protect and sustain the forest, the water, and the people of Kohala Mountain". Hawaii Association of Watershed Partnerships. 2008. Archived from the original on 10 July 2009. Retrieved 15 December 2009.

- ^ Ralph H. Riley; Peter M. Vitousek (1995). "Nutrient Dynamics and Nitrogen Trace Gas Flux During Ecosystem Development in Montane Rain Forest". Ecology. 76 (1): 292–304. doi:10.2307/1940650. ISSN 0012-9658. JSTOR 1940650.

- ^ a b Thegn N. Ladefoged; Michael W. Gravesb; Mark D. McCoy (July 2003). "Archeological Evidence for agricultural development in Kohala, Island of Hawaiʻi" (PDF). Journal of Archaeological Science. 30 (7): 923–940. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.535.2842. doi:10.1016/s0305-4403(02)00271-6. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2011-06-06. Retrieved 2009-12-18.

- ^ a b S. Schweitzer, Veronica (2006). "Sugar and Steam in Kohala". Coffee Times. Archived from the original on 15 December 2010. Retrieved 25 December 2009.

- ^ a b S. Schweitzer, Veronica (2006). "Kohala Ditch". Coffee Times. Archived from the original on 3 January 2010. Retrieved 25 December 2009.

- ^ "Flumin' da Ditch". web site. Retrieved 2009-12-25.

- ^ "The Kohala Center". The Kohala Center. 2008. Retrieved 16 December 2009.

- ^ "Kohala Coast vacation on the Big Island of Hawaii". www.kohalacoastweb.com. 2009. Archived from the original on 2009-10-19. Retrieved 2009-11-07.

- ^ Sperling, Kandra (2009). "Island of Hawaii Golf Courses". MerchantCircle. Retrieved 2009-11-07.

Further reading

[edit]- Macdonald, Gordon A.; Abbott, Agatin Townsend; Peterson, Frank L. (1983). Volcanoes in the Sea: The Geology of Hawaii. University of Hawaii Press. ISBN 978-0-8248-0832-7.

- Wood, Charles A.; Jürgen Kienle (1992). Volcanoes of North America: The United States and Canada. Cambridge University Press. pp. 337–339. ISBN 978-0-521-43811-7.

- "Kohala". Global Volcanism Program. Smithsonian Institution.