Transcendental Meditation movement

The Transcendental Meditation movement (TM) are programs and organizations that promote the Transcendental Meditation technique founded by Maharishi Mahesh Yogi in India in the 1950s. The organization was estimated to have 900,000 participants in 1977,[1] a million by the 1980s,[2][3][4] and 5 million in more recent years.[5][6][7][8][9][10][11]

Programs include the Transcendental Meditation technique, an advanced meditation practice called the TM-Sidhi program ("Yogic Flying"), an alternative health care program called Maharishi Ayurveda,[12] and a system of building and architecture called Maharishi Sthapatya Ved.[13][14] The TM movement's past and present media endeavors include a publishing company (MUM Press), a television station (KSCI), a radio station (KHOE), and a satellite television channel (Maharishi Channel). Its products and services have been offered primarily through nonprofit and educational outlets, such as the Global Country of World Peace, and the David Lynch Foundation.

The TM movement also operates a worldwide network of Transcendental Meditation teaching centers, schools, universities, health centers, and herbal supplement, solar panel, and home financing companies, plus several TM-centered communities. The global organization is reported to have an estimated net worth of USD 3.5 billion.[15][16]

The TM movement has been called a spiritual movement, a new religious movement,[17][18] a millenarian movement, a world affirming movement,[19] a new social movement,[20] a guru-centered movement,[21] a personal growth movement,[22] and a cult.[18][23][24][25] TM is practiced by people from a diverse group of religious affiliations.[26][27][28][29]

History

[edit]Maharishi Mahesh Yogi began teaching Transcendental Meditation in India in the late 1950s.[30] The Maharishi began a series of world tours in 1958 to promote his meditation technique.[31] The resulting publicity generated by the Maharishi, the celebrities who learned the technique and the scientific research into its effect, helped popularize the technique in the 1960s and 1970s. In the 1970s the Maharishi introduced advanced meditative techniques and his movement grew to encompass TM programs for schools, universities and prisons. In the 1980s additional programs aimed at improved health and well-being were developed based on the Maharishi's interpretation of the Vedic traditions. By the late 2000s, TM had been taught to millions of individuals and the Maharishi oversaw a large multinational movement which has continued since his death in 2008. The Maharishi's obituary in the New York Times credited the TM movement as being "a founding influence on what has grown into a multibillion-dollar self-help industry".[32]

Practitioners and participants

[edit]The TM movement has been described as a "global movement" that utilizes its own international policies and transports its "core members" from country to country.[33][page needed] It does not seek to interfere with its member's involvement in their various religions.[33][page needed]

In 2008, The New York Times, reported that TM's "public interest" had continued to grow in the 1970s" however, some practitioners were discouraged "by the organization's promotion of ....Yogic Flying."[32] The organization was estimated to have 900,000 participants worldwide in 1977 according to new religious movement scholars Stark, Bainbridge and Sims.[1] That year the TM movement said there were 394 TM centers in the U.S., that about half of the 8,000 trained TM teachers were still active, and that one million Americans had been taught the technique.[34] The movement was reported to have a million participants by the 1980s,[2][3][4] and modern day estimates range between four and ten million practitioners worldwide.[5][6][9][11][35][36][37][38] As of 1998, the country with the largest percentage of TM practitioners was Israel, where 50,000 people had learned the technique since its introduction in the 1960s, according members of the TM movement.[39] In 2008, the Belfast Telegraph reported that an estimated 200,000 Britons practiced TM.[40]

The TM movement has a flexible structure that allows varying degrees of commitment.[33][page needed] Many are satisfied with their "independent practice of TM" and don't seek any further involvement with the organization.[33][page needed] For many TM practitioners their meditation is "one of many New Age products that they consume." Other practitioners are "dedicated" but are also critical of the organization. Still others, are "highly devoted" and participate in "mass meditations" at Maharishi University of Management, perform administrative activities or engage in a monastic lifestyle. Likewise the organization has a "loose organisational hierarchy".[33][page needed] Transcendental Meditators who participate in group meditations at Maharishi University of Management are referred to as "Citizens of the Age of Enlightenment".[41][42] Regional leaders[43] and "leading Transcendental Meditators" trained as TM teachers and graduates of the TM-Sidhi program[44] are called "Governors of the Age of Enlightenment".[41] There are also "national leaders" and "top officials" of the "World Peace Government" that are called Rajas.[33][page needed]

Notable practitioners

[edit]Notable practitioners include politicians John Hagelin and Joaquim Chissano; musicians Donovan, The Beatles, Sky Ferreira, and Mike Love; celebrities David Lynch, Clint Eastwood, Mia Farrow, Howard Stern, Doug Henning; and artist Ned Bittinger.[45] Practitioners who became spiritual teachers or self-help authors include Sri Sri Ravi Shankar, Deepak Chopra, John Gray and Barbara De Angelis.

TM-initiated celebrities include Gwyneth Paltrow, Ellen DeGeneres, Russell Simmons, Katy Perry, Susan Sarandon, Candy Crowley, Soledad O’Brien, George Stephanopoulos, and Paul McCartney's grandchildren.[46] As of 2013, Jerry Seinfeld had been practicing TM for over 40 years.[47]

Oprah Winfrey and Dr. Oz dedicated an entire show to TM.[46]

Programs

[edit]Transcendental Meditation

[edit]

The Transcendental Meditation technique is a specific form of mantra meditation[48] developed by Maharishi Mahesh Yogi. It is often referred to as Transcendental Meditation or simply, TM. The meditation practice involves the use of a mantra, and is practiced for 15–20 minutes twice per day, while sitting with closed eyes.[49][50] It is reported to be one of the most widely practiced,[51][52] and among the most widely researched, meditation techniques,[53] with hundreds of studies published.[54][55][56] The technique is made available worldwide by certified TM teachers in a seven step course[49][57] and fees vary from country to country.[58][59] Beginning in 1965, the Transcendental Meditation technique has been incorporated into selected schools, universities, corporations and prison programs in the United States, Latin America, Europe, and India. In 1977, the TM technique and the Science of Creative Intelligence were deemed religious activities as taught in two New Jersey public schools. Subsequently the TM technique has received some governmental support.[60]

The Transcendental Meditation technique has been described as both religious and non religious. The technique has been described in various ways including as an aspect of a New Religious Movement, as rooted in Hinduism,[61][62][63] and as a non-religious practice for self development.[64][65][66] The public presentation of the TM technique over its 50-year history has been praised for its high visibility in the mass media and effective global propagation, and criticized for using celebrity and scientific endorsements as a marketing tool. Advanced courses supplement the TM technique and include an advanced meditation called the TM-Sidhi program. In 1970, the Science of Creative Intelligence (SCI) became the theoretical basis for the Transcendental Meditation technique, although skeptics questioned its scientific nature.[67] According to proponents, when 1 percent of a population (such as a city or country) practices the TM technique daily, their practice influences the quality of life for that population. This has been termed the Maharishi Effect.

TM technique in education

[edit]

Transcendental Meditation in education (also known as Consciousness Based Education) is the application of the Transcendental Meditation technique in an educational setting or institution. These educational programs and institutions have been founded in the United States, United Kingdom, Australia, India, Africa and Japan. The Transcendental Meditation technique became popular with students in the 1960s and by the early 1970s centers for the Students International Meditation Society were established at a thousand campuses[68] in the United States, with similar growth occurring in Germany, Canada and Britain.[69] The Maharishi International University was established in 1973 in the United States and began offering accredited, degree programs. In 1977 courses in Transcendental Meditation and the Science of Creative Intelligence (SCI) were legally prohibited from New Jersey (US) public high schools on religious grounds by virtue of the Establishment Clause of the First Amendment.[70][71] This "dismantled" the TM program's use of government funding in U.S. public schools[72] but did not render "a negative evaluation of the program itself".[73] Since 1979, schools that incorporate the Transcendental Meditation technique using private, non-governmental funding have been reported in the United States, South America, Southeast Asia, Northern Ireland, South Africa and Israel.[74][75][76]

A number of educational institutions have been founded by Maharishi Mahesh Yogi, the Transcendental Meditation movement and its supporters. These institutions include several schools offering public and private secondary education in the United States (Maharishi School of the Age of Enlightenment),[77] England (Maharishi School),[78][79] Australia,[80][81][82] South Africa (Maharishi Invincibility School of Management),[83] and India (Maharishi Vidya Mandir Schools). Likewise, Maharishi colleges and universities have been established including Maharishi European Research University (Netherlands), Maharishi Institute of Management (India), Maharishi Institute of Management (India), Maharishi University of Management and Technology (India), Maharishi Institute (South Africa)[84][85] and Maharishi Mahesh Yogi Vedic University (India). In the United States, critics have called Transcendental Meditation a revised form of Eastern, religious philosophy and opposed its use in public schools[86] while a member of the Pacific Justice Institute says practicing Transcendental Meditation in public schools with private funding is constitutional.[87]

TM-Sidhi program

[edit]The TM-Sidhi program is a form of meditation introduced by Maharishi Mahesh Yogi in 1975. It is based on, and described as a natural extension of the Transcendental Meditation technique (TM).[88][89] The goal of the TM-Sidhi program is to enhance mind-body coordination[90] and to support the "holistic development of consciousness"[91] by training the mind to think from what the Maharishi called a fourth state of consciousness.[92] "Yogic Flying", a mental-physical exercise of hopping while cross-legged,[93][94] is a central aspect of the TM-Sidhi program. The TM website says that "research has shown a dramatic and immediate reduction in societal stress, crime, violence, and conflict—and an increase in coherence, positivity, and peace in society as a whole" when the TM-Sidhi program is practiced in groups.[95] This is termed the Maharishi Effect. While empirical studies have been published in peer-reviewed academic journals[96] they have been met with both skepticism and criticism. Skeptics have called TM's associated theories of the Science of Creative Intelligence and the Maharishi Effect, "pseudoscience".[97][98][99] It is difficult to determine definitive effects of meditation practices in healthcare as the quality of research has design limitations and a lack of methodological rigor.[100][101][102]

Maharishi Ayurveda

[edit]Maharishi Ayurveda,[103][104][105] also known as Maharishi Vedic Approach to Health[106][107] and Maharishi Vedic Medicine[108] is considered an alternative medicine designed as a complementary system to modern western medicine.[109] The approach was founded internationally in the mid 1980s by Maharishi Mahesh Yogi. The Maharishi's revised system of Ayurveda was endorsed by the "All India Ayurvedic Congress" in 1997.[citation needed] The Transcendental Meditation technique is part of the Maharishi Vedic Approach to Health (MVAH).[110] According to the movement's Global Good News website, there are 23 Maharishi Vedic Health Centres in 16 countries, including Austria, France, Denmark, Germany, India, Israel, Italy, Japan, the Netherlands, New Zealand, Norway, South Africa, Switzerland, Turkey, United Kingdom, and the United States.[111] The Maharishi Ayurvedic Centre in Skelmersdale, UK also offers panchakarma detoxification.[112]

Maharishi Sthapatya Veda

[edit]Maharishi Sthapatya Veda (MSV) is a set of architectural and planning principles assembled by Maharishi Mahesh Yogi based on "ancient Sanskrit texts"[13][14] as well as Vastu Shastra, the Hindu science of architecture.[113] Maharishi Sthapatya Veda architecture is also called "Maharishi Vastu" architecture, "Fortune-Creating" buildings and homes,[114] and "Maharishi Vedic architecture".[115] According to its self-description, the system consists of "precise mathematical formulas, equations, and proportions" for architectural design and construction. MSV has strict rules governing the orientation and proportions of a building.[116] The most important factor is the entrance, which must be either due east or due north.[116] The MSV architect also considers the slope and shape of the lot, exposure to the rising sun, location of nearby bodies of water and the other buildings or activities in the nearby environment.[117] MSV emphasizes the use of natural or "green" building materials.[9][13] The TM movement's aspiration is to have global reconstruction to create east-facing entrances, at an estimated cost of $300 trillion.[118][119]

Settlements

[edit]

About 3,000 TM practitioners are estimated to live near MUM and the Golden Domes in Fairfield, Iowa, US,[120] an area dubbed "Silicorn Valley" by locals.[121] By 2001, Fairfield's mayor and some city council members were TM practitioners.[120] Just outside the city limits is Maharishi Vedic City. The city's 2010 population of 1,294 includes about 1,000 pandits from India who live on a special campus.[122][123] The city plan and buildings are based on Maharishi Sthapatya Veda, an ancient system of architecture and design revived by the Maharishi.[124][125]

A community called Sidhadorp was established in the Netherlands in 1979 and reached its completion in 1985.[126] Around the same time Sidhaland, in Skelmersdale UK was established with about 400 TM practitioners, a meditation dome, and a TM school.[33][page needed][127] There is also a housing project in Lelystad, the Netherlands.[128] Hararit (Hebrew: הֲרָרִית) is a settlement in Galilee, Israel founded in 1980, as part of a "government-sponsored project" by a group of Jewish practitioners of the Transcendental Meditation program.[33][page needed] It is the home for about 60 families.[129] There are several residential facilities in India, including a 500-acre (2.0 km2) compound in "Maharishi Nagar", near Noida.[130] There is a 70-unit development, Ideal Village Co-Op Inc, in Orleans, Ontario, a suburb of Ottawa, where 75 percent of the residents have been TM meditators.[131]

Monastic communities

[edit]Purusha and Mother Divine are the names of gender specific communities who lead a lifestyle of celibacy and meditation.[132][133] Some residents have been part of the community for 20 years or more.[134][135]

In 1990 the Purusha community consisted of 200 men who conducted "administrative and promotional details" for the Maharishi's worldwide organization.[136] The Purusha group was originally located at the Spiritual Center of America in Boone, North Carolina, US.[137] As of 2002 there were 300 male residents whose daily routine consisted of meditation from 7 am to 11:30 am and another group meditation in the evening. The rest of the day was taken up by lunch, educational presentations, fundraising and work for "non-profit entities associated with the Spiritual Center". The residents also read Vedic literature, studied Sanskrit, received monthly instruction from the Maharishi via teleconference and engaged in discourse with faculty of Maharishi University of Management.[134] As of 2007, there was also a Purusha community of 59 men in Uttarkashi, India.[138] In 2012 the USA Purusha group moved to a newly constructed campus called the West Virginia Retreat Center, located in Three Churches, West Virginia, US. The campus consists of 10 buildings and 90 males residents plus staff.[139]

As of 2002 the 100 resident Mother Divine community for women was also located at the Spiritual Center in Boone, North Carolina[137] as part of an organization called Maharishi Global Administration Through Natural Law. Their daily routine was similar to the Purúsha community and in addition they operated The Heavenly Mountain Ideal Girls' School, a fully accredited North Carolina non-public school for grades 9 through 12.[134]

Publishing, TV and radio

[edit]MIU Press

[edit]Maharishi International University (MIU) Press was founded in the 1970s and operated a full-scale printing operation to publish the organization's brochures and literature for the United States. The Press employed four printing presses and 55 employees [140] and was located at the Academy for the Science of Creative Intelligence in Livingston Manor, New York.[141] MIU Press later became Maharishi University of Management (MUM) Press.[41] MUM Press published books, academic papers, audio and video recordings and other educational materials.[142][143] These materials include the Modern Science and Vedic Science journal and books by Maharishi Mahesh Yogi, John Hagelin, Tony Nader, Robert Roth, Craig Pearson, Robert Oates, Ashley Deans, and Robert Keith Wallace as well as ancient Sanskrit works by Bādarāyaṇa, Kapila, and Jaimini.[144] In addition their World Plan Television Productions contained a film library and audio and TV production studios, with $2 million worth of equipment, which distributed 1,000 videos each month to their TM teaching centers.[140]

KSCI TV station

[edit]In 1975, the television station called channel 18 became KSCI [145] and began production from a studio in West Los Angeles, while still licensed in San Bernardino.[146] The station became a non-profit owned by the Transcendental Meditation movement and the call letters stood for Maharishi Mahesh Yogi's theoretical "Science of Creative Intelligence". The station broadcast began with 56 hours per week of "uplifting" news stories, prerecorded lectures by the Maharishi and variety shows featuring celebrities who practiced the Transcendental Meditation technique.[140][145] KSCI's goal was to report "only good news" and seven sister stations were planned including San Francisco, Washington, D.C. and Buffalo, New York.[140][141][145] The station manager was Mark Fleischer, the son of Richard Fleischer, a Hollywood director.[141] The Los Angeles location leased $95,000 worth of equipment and its highest paid staff member earned $6,000 according to tax documents.[140]

In 1980 the station switched to for-profit status and earned $1 million on revenues of $8 million in 1985.[147] In November, owners of the KSCI TV station loaned $350,000 to Maharishi International University in Iowa.[148][149] [need quotation to verify] As of June 1986 the station's content consisted of "a hodgepodge of programming in 14 languages" that was broadcast on both cable and UHF in Southern California.[146] In October, the station was purchased by its general manager and an investor for $40.5 million.[150]

KHOE radio station

[edit]KHOE, is a low-power, non-profit radio station belonging to Maharishi University of Management (MUM), which began broadcasting in 1994.[151][152] The station features music and educational entertainment from around the globe including American music and cultural and ethnic programming. MUM's international students present music, poetry and literature from their native countries.[152] KHOE also broadcasts classical Indian (Maharishi Ghandarva Veda) music 24 hours per day on a special sideband.[152]

Satellite TV

[edit]Maharishi Veda Vision is a satellite broadcast that began in 1998 with three hours of evening programming.[153] Programing expanded to 24 hours a day by 1999.[154] Maharishi Veda Vision was described as India's first religious television channel.[154] The Maharishi Channel Cable Network, owned by Maharishi Satellite Network, was reported to have moved to Ku band digital satellites in 2001. While providing Vedic wisdom in 19 languages, most of the channel's programming was in Hindi and was intended for the worldwide non-resident Indian population.[155] By 2002 the channel was carried on eight satellites serving 26 countries. The channel had no advertisements, depending on a "huge network of organisations, products and services" for support.[156] In 2005, the channel was among several religious channels vying to get space on DD Direct+.[157] Additional channels are broadcast over satellite as part of the Maharishi Open University's distance learning program, which also has studio facilities at Maharishi Vedic City in Iowa.[158] The Maharishi Channel, which originates in the Netherlands, had a pending request for a downlink to India as of July 2009.[159] According to its website, Ramraj TV is being established in India to introduce Vedic principles and practical programmes to the "World Family". As of August 2010, it is only available on the Internet. On a webpage last updated August 2009, the channel says it is in the process of obtaining a license from the Indian Government for a satellite uplink and downlink.[160]

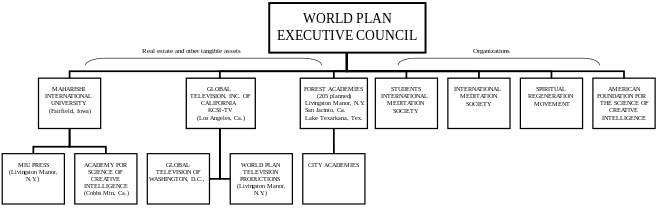

Organizations

[edit]The International Foundation for the Science of Creative Intelligence (IFSCI).[161][162] American versions and additions to these organizations included the Spiritual Regeneration Movement Foundation (SRMF), the World Plan Executive Council which was established to serve as a guide for the movement there [163] and the American Foundation for the Science of Creative Intelligence, for people in business and education.[161] Active international organizations include the International Meditation Society, Maharishi Foundation, Global Country of World Peace and the David Lynch Foundation.

In 2007, the organization's "worldwide network" was reported to be primarily financed through courses in the Transcendental Meditation technique with additional income from donations and real estate assets.[164] Valuations for the organization are US$300 million in the United States[165][166] and $3.5 billion worldwide.[15][167]

Historically listed

[edit]1958: Spiritual Regeneration Movement and Foundation

[edit]The Spiritual Regeneration Movement was established in India in 1958[168][169] and the Spiritual Regeneration Movement Foundation (SRMF) was incorporated in California, US, in July 1959 as a non-profit organization, with its headquarters in Los Angeles.[169][170] SRMF's articles of incorporation describe the corporate purpose as educational and spiritual. Article 11 of the articles of incorporation read: "this corporation is a religious one. The educational purpose shall be to give instruction in a simple system of meditation".[170][171][172] The SRMF corporation was later [when?] dissolved.[170] SRM offered TM courses to individuals "specifically interested in personal development in the context of a spiritual, holistic approach to knowledge".[173] SRM addressed a smaller and older segment of the population as compared with subsequent organizations such as the International Meditation Society and the Students International Meditation Society.[174] According to British author Una Kroll, SRM was not a community and in the early 1970s the organization "cast off its semi-religious clothing and pursued science in a big way".[175]

In January 2012 the Pioneer News Service, New Delhi, reported that several trusts, including the SRM Foundation of India, had become "non-functional" after the death of the Maharishi in 2008 and were immersed in controversy after trust members alleged that parcels of land had been "illegally sold off" by other trust members without proper authorization.[176] In June the dispute was reported to be specifically between members of the SRM Foundation India, board of directors, over control of the foundation's assets, including 12,000 acres of land spread around India. The two factions had accused each other of forging documents and selling land for "personal gains" without the sanction of the entire 12-member board. The two parties petitioned the Indian courts for a stay of all land sales until the Department and the Ministry of Home Affairs could conduct an investigation of the alleged improprieties. The newspaper went on to report that only four years after the Maharishi's death, his Indian legacy was "in tatters". [177]

1959: International Meditation Society

[edit]In 1959 the Maharishi went to England and established the British arm of the International Meditation Society with an additional office in San Francisco California, US.[178][179] The International Meditation Society was founded in the U.S. in 1961 to offer both beginning and advanced courses in Transcendental Meditation to the general public.[145][168][173] As of 2007 it was still an active organization in Israel.[180][181]

1965: Students International Meditation Society

[edit]The Students International Meditation Society (SIMS) was first established in Germany in 1964.[68] A United States chapter was created in 1965 and offered courses to students and the youth of society.[173][182] The UCLA (University of California, Los Angeles) chapter of SIMS, which had 1,000 members, was founded by Peter Wallace and his brother Robert Keith Wallace, the first president of Maharishi International University.[168][183] In the 1970s, SIMS centers were established at "over one thousand campuses"[68] in the United States, and similar growth occurred in Germany, Canada and Britain.[69]

1970: International Foundation for the Science of Creative Intelligence

[edit]Transcendental Meditation has been utilized in corporations, both in the United States and in India, under the auspices of the International Foundation for the Science of Creative Intelligence and the Maharishi Development Corporation. In India a number of companies provide the TM technique to their managers. These companies include AirTel, Siemens, American Express, SRF Limited, Wipro, Hero Honda, Ranbaxy, Hewlett-Packard, BHEL, BPL Group, ESPN Star Sports, Tisco, Eveready, Maruti, Godrej Group and Marico.[184] The employees at Marico practice Transcendental Meditation in groups as part of their standard workday.[184] The US branch of the organization is called the American Foundation for the Science of Creative Intelligence (AFSCI)[145][173] and as of 1975 it had conducted TM courses at General Foods, AT&T Corporation Connecticut General Life Insurance Company and Blue Cross/Blue Shield.[145] As of 2001, US companies such as General Motors and IBM were subsidizing the TM course fee for their employees.[185] The organization has been described as one of several "holistic health groups" that attempted to incorporate elements of psychology and spirituality into healthcare.[186]

The Maharishi Corporate Development Program is another international non-profit organization that offers the TM program to people in industry and business.[187][188] According to religious scholar Christopher Partridge, "hundreds" of Japanese business' have incorporated the meditation programs offered by Maharishi Corporate Development International[189] including Sumitomo Heavy Industries Ltd.[190] In 1995 the Fortune Motor Co. of Taiwan reportedly had a 100% increase in sales after participating in the program.[190] The Washington Post reported in 2005, that US real estate developer, The Tower Companies, had added classes in Transcendental Meditation to their employee benefit program with 70% participation.[191][192][193]

1972: World Plan Executive Council

[edit]

The World Plan Executive Council's (WPEC) international headquarters were located in Seelisberg, Switzerland and its American headquarters in Washington, D.C.[194] The organization name was taken from the Maharishi's "world plan",[195] which aimed to develop the full potential of the individual; improve governmental achievements; realize the highest ideal of education; eliminate the problems of crime and all behavior that brings unhappiness to the family of man; maximize the intelligent use of the environment; bring fulfillment to the economic aspirations of individuals and society; and achieve the spiritual goals of mankind in this generation.[31] It provided courses in the Transcendental Meditation technique and other related programs.[196][197][failed verification]

It was founded in Italy in 1972 and by 1992 had organized twenty-five TM centers with thirty-five thousand participants in that country.[198] In 1998 the World Plan Executive Council Australia (WPECA) sought the approval of the New South Wales Labor Council (NSWLC) to allow a resort on property owned by NSWLC.[199]

The World Plan Executive Council (WPEC) was established in the U.S. as a non-profit educational corporation to guide its Transcendental Meditation movement.[163] Its president was an American and former news reporter named Jerry Jarvis and the Maharishi is reported to have had "no legal, official or paid relationship with WPEC".[140][200] WPEC was an umbrella organization and operated almost exclusively on revenues generated from TM course fees.[140] It featured corporate trappings such as "computerized mailings, high-speed communications, links, even a well-turned medical and life insurance plan for its employees".[140] WPEC supervised the 375 urban TM centers as well as several failed resorts that were purchased or leased as "forest academies" for in-residence meditation classes and courses.[140] It had $40 million in tax exempt revenues from 1970 to 1974[140] and in 1975 it had $12 million in annual revenues but [145] did not employ any outside public relations firm.[140]

In 1985, a civil suit were filed against the World Plan Executive Council, in the United States by Robert Kropinski, Jane Greene, Patrick Ryan and Diane Hendel[201] claiming fraud and psychological, physical, and emotional harm as a result of the Transcendental Meditation and TM-Sidhi programs. The district court dismissed Kropinski's claims concerning intentional tort and negligent infliction of emotional distress, and referred the claims of fraud and negligent infliction of physical and psychological injuries to a jury trial. The jury awarded Kropinski $137,890 in the fraud and negligence claims. The appellate court overturned the award and dismissed Kropinski's claim alleging psychological damage. The claim of fraud and the claim of a physical injury related to his practice of the TM-Sidhi program were remanded to the lower court for retrial.[202] Kropinski, Green, Ryan and the defendants settled the remaining claims out of court on undisclosed terms.[203] The remaining suit by Hendel, not included in the settlement, was later dismissed because the claims were barred by the statute of limitations. In affirming the dismissal, the Court of Appeals for the DC Circuit held that Hendel's claims were time-barred under the discovery rule because "...the defendants made representations which any reasonable person would recognize as being contrary to common human experience and, indeed, to the laws of physics. If, as Ms. Hendel alleges, she was told that meditators would slowly rise in the air, and that some of them were 'flying over Lake Lucern' or 'walking through walls, hovering, and becoming invisible,' and that her failure to go to bed on time could bring about World War III, then a reasonable person would surely have noticed, at some time prior to September 1, 1986, that some of these representations might not be true."[204]

In the 1990s WPEC in the United States became the parent company to an American, for-profit, hotel subsidiary called Heaven on Earth Inns Corp. with Thomas M. Headley as its president. The Heaven on Earth Inns Corp. was reported to have purchased nine US hotels at cut-rate prices that year, including two in Ohio, one in Oklahoma[205] and one in Omaha, Nebraska.[206][207] The hotels were bought as facilities for TM classes and as income-producing operations for health-conscious travelers who preferred vegetarian meals, alcohol free environments and non-smoking accommodations.[208] The following year WPEC purchased a hotel in Asbury Park, New Jersey[209] and a "shuttered" hotel in St. Louis, Missouri.[210] WPEC also "took over" Chicago's Blackstone Hotel via foreclosure in 1995.[211]

The Maharishi Global Development Fund (MGDF) purchased the Clarion Hotel in Hartford, Connecticut, US, in 1995 for $1.5 million and sold it to Wonder Works Construction in 2011.[212] In 2006 MGDF's assets were listed as $192.3 million with $51.4 million in income.[213]

1975: Maharishi Foundation

[edit]Maharishi Foundation is an educational and charitable organization[214] active in at least four countries. The Maharishi Foundation's headquarters resided at Mentmore Towers in Buckinghamshire beginning in 1978[214] and later moved to Skelmersdale, West Lancashire, England.[215] According to its website, Maharishi Foundation is a "registered, educational charity" that was established in Northern Ireland and the United Kingdom in 1975.[216] Its purpose is to advance public education by offering courses and services for human development including Transcendental Meditation.[216][217] The foundation is said to promote Consciousness-Based Education and research on Transcendental Meditation by "independent academic institutions"[216] and reported $7 million in revenues in 2010.[218] Similar corporations include the Maharishi Foundation Incorporated in New Zealand[219] and Maharishi Foundation U.S.A.[220] Maharishi Foundation purchased the Kolleg St. Ludwig campus in 1984 for USD 900,000[221] and it became the Maharishi European Research University (MERU) campus as well as the Maharishi's movement headquarters and residence.[32] The buildings were old, inefficient, in disrepair and did not meet the Maharishi Sthapatya Veda requirements of an east facing entrance.[221] A 2006 report in the LA Times said the Maharishi's organization has been involved in a two year "courtroom battle" with preservationist who wanted to block the demolition of the Kollege St. Ludwig building which "was abandoned in 1978" by its previous owners.[222] A three-story, canvas illustration of the intended replacement building was put up on the front side of the building but local government ordered its removal.[223] According to a 2008 report, the MERU Foundation indicated it would consider leaving the site if permission to demolish the old building was not granted.[223] In 2015, the old buildings were removed completely.[224]

By 1996, it was referred to as the "Maharishi Continental Capital of the Age of Enlightenment for Europe".[225] In 1998, the overall redevelopment plan for the location was budgeted at USD 50 million.[221] Aerial photographs show the development of the site.[226][227] Floodlights illuminated the new building constructed in 1997 and 164 flagpoles carried the flags of the world nations "like a meditation-based United Nations."[228] Local authorities later limited the use of floodlights and required removal of the flagpoles.[223] Tony Nader was crowned Maharaja Raja Raam there in 2001,[229] and it became a "capital" of the Global Country of World Peace.[230] By 2006, the campus had 50 residents and had been visited by John Hagelin[32] and Doug Henning in prior years.[230][231][232]

In November 2011 Maharishi Foundation USA filed a lawsuit in Federal court against The Meditation House LLC for infringement of the foundation's Transcendental Meditation trademark which are licensed to select organizations.[233][234] The foundation alleges that its "credibility and positive image" are being used to "mislead customers" while the defendant asserts the foundation has an unfair monopoly on an ancient technique.[218]

1976: World Government of the Age of Enlightenment

[edit]This self described non-political, non-religious, global organization was formed in 1976 by the Maharishi[235] As of 1985 the World Government of the Age of Enlightenment was administrated by its president, Thomas A. Headly. Its purpose was to teach the Science of Creative Intelligence and the Transcendental Meditation and TM-Sidhi programs and to accomplish the seven goals of the World Plan. In addition, the organization gave Maharishi Awards to several outstanding members of the community each year.[173]

1988: Maharishi Heaven on Earth Development Corp.

[edit]Maharishi Heaven on Earth Development Corp. (MHOED) is a for-profit real estate developer associated with Maharishi Mahesh Yogi and his Transcendental Meditation movement. First founded in Malibu California in 1988, it has sought to build utopian projects in the U.S., Canada, and Africa with a long-term goal to "reconstruct the entire world", at an estimated cost of $100 trillion.[236][237] The US arm planned to work with developers to build 50 "Maharishi Cities of Immortals" in the US and Canada.[238] The Canadian arm bought and renovated the Fleck/Paterson House in Ottawa in 2002, earning the "adaptive use award of excellence" from the City.[239] A subsidiary purchased land to build Maharishi Veda Land theme parks in Orlando, Florida and Niagara Falls, New York. The Dutch arm negotiated with the presidents of Zambia and Mozambique to acquire a quarter of the land in those countries in exchange for solving their problems.

1992: Natural Law Party

[edit]Founded in 1992, the Natural Law Party (NLP) was a transnational party based on the teachings of Maharishi Mahesh Yogi.[240] The party was founded on the concept that Natural Law is the organizing principle that governs the universe and that the problems of humanity are caused by people violating Natural Law. The NLP supported using scientifically verifiable procedures such as the Transcendental Meditation technique and TM-Sidhi program to reduce or eliminate the problems in society. The party was active in up to 74 countries and ran candidates in many countries including the United States, Canada, United Kingdom, Ireland, Australia, New Zealand, Germany, Israel, and Taiwan.[241]

Two of the most prominent candidates were John Hagelin, who campaigned for U.S. president in 1992, 1996 and 2004, and magician Doug Henning who ran for office in England. Electoral successes were achieved by the Ajeya Bharat Party in India, which elected a legislator to a state assembly, and by the Croatian NLP, which elected a member of a regional assembly in 1993.[242] The party was disbanded in some countries beginning in 2004 but continues in India and in a few U.S. states.[243]

1993: Maharishi Vedic Education Development Corporation

[edit]Maharishi Vedic Education Development Corporation (MVEDC) is a non-profit, American organization, incorporated in 1993 and headquartered in Fairfield, Iowa.[244] Bevan G. Morris is the acting and founding president of the corporation and Richard Quinn is the director of project finance.[245][246][247] MVED's primary purpose is the administration of Transcendental Meditation courses and training TM instructors in the United States.[248][249][250] Courses in Transcendental Meditation are led by TM teachers trained by MVED.[251][252] MVED also provides promotional literature to its teachers and TM centers.[253][254]

In 1975 the US non-profit oversaw five owned properties and hundreds of rented facilities that offered meditation lectures and seminars. One facility located in Livingston Manor, New York housed a 350-room hotel, a printing press and a professional quality video and sound-recording studio.[145] MVED is the sublicensee for many trademarks owned by the U.K. non-profit Maharishi Foundation Ltd. These trademarks include: Transcendental Meditation, TM-Sidhi, Yogic Flying and Maharishi Vedic Approach to Health.[255][233][256]

In 2004, the lawsuit Butler vs. MUM alleged that MVED was guilty of negligent representation and had direct liability for the death of a Maharishi University of Management student. In 2008, all charges against MVED were dismissed and the law suit was dropped.[257][258][259][260][261][262] According to journalist Antony Barnett, the attacks led critics to question the movement's claims that group practice of advanced meditation techniques could end violence.[263] Maharishi said of the incident that "this is an aspect of the violence we see throughout society", including the violence that the U.S. perpetrates in other countries.[263]

MVED has created educational enterprises, such as Maharishi Vedic University and Maharishi Medical Center, and has overseen the construction and development of Maharishi Peace Palaces owned by the Global Country of World Peace (GCWP) in 30 locations in the United States.[264][265][266] Maharishi Peace Palaces, Transcendental Meditation Centers, Maharishi Enlightenment Centers, and Maharishi Invincibility Centers provide training and Maharishi Ayurveda treatments as well as serving as local centers for TM and TM-Sidhi practitioners.[253][267]

1997: Maharishi Housing Development Finance Corporation

[edit]The Maharishi Housing Development Finance Corporation (MHDFC) was established in India in 1997 and as of 2003 had 15 branch offices.[268] In 2000 MHDFC began offering seven and 15-year loans and proposed a plan to offer 40-year mortgages.[269] By 2003 the finance company had 15 branches across India, a loan portfolio of Rs104 crore, and the Maharishi University of Management of UK was listed as its majority owner.[268][270][271][272] In 2009 Religare Enterprises Limited acquired an 87.5 percent stake in MHDFC and on that basis MHDFC received the highest quality credit rating from the ICRA in 2010.[273][274]

1999: Maharishi Solar Technology

[edit]Maharishi Solar Technology (MST) is an Indian solar producer that makes modules, solar lanterns and pumps founded in 1999.[275][276] MST has a vertically integrated facility for producing photovoltaic panels at Kalahasti in Andhra Pradesh,[277] and is a core producer of the multicrystalline silicon wafers used to make them.[278] MST is reported to be a "venture of Maharishi group" and has contracted with the US-based Abengoa Solar Inc to produce solar thermal collectors.[279][280] MST's president, Prakash Shrivastava [281] is a member of the Solar Energy Society of India's Governing Council.[282] According to a press release published in Reuters, MST was included in the "2011–2015 Deep Research Report on Chinese Solar Grade Polysilicon Industry".[283]

2001: Global Country of World Peace

[edit]

The Global Country of World Peace (GCWP) was declared by Maharishi Mahesh Yogi, the founder of Transcendental Meditation, on Vijayadashami (Victory Day), 7 October 2000.[284] He described it as "a country without borders for peace loving people everywhere".[285][286] GCWP is structured as a kingdom, with Tony Nader as its current Maharaja or Sovereign Ruler.[287] It became incorporated in the state of Iowa, US, on 15 October 2002 as a non-profit organization with Bevan Morris as its president.[288] The corporation has its headquarters in Maharishi Vedic City, Iowa.[288][289] It has, or is building, capitals in the Netherlands, Iowa, Kansas, West Virginia, Manhattan, and India. The GCWP has made various unsuccessful attempts at attaining sovereignty as a micronation during the years 2000 to 2002, offering sums in excess of $1 billion to small and impoverished countries in exchange for the sovereignty over part of their territory. It has a global reconstruction program which seeks to rebuild all of the cities and buildings in the world following Maharishi Sthapatya Veda principles.

2005: David Lynch Foundation

[edit]The David Lynch Foundation For Consciousness-Based Education and World Peace is a charitable foundation based in Fairfield, Iowa,[290] founded in 2005 and operating worldwide. The Foundation primarily funds at-risk students learning to meditate using the Transcendental Meditation program. Its other activities include funding research on Transcendental Meditation and fundraising with the long-term goal of raising $7 billion to establish seven affiliated "Universities of World Peace", to train students in seven different countries to become "professional peacemakers".[291][292]

Other

[edit]The Academic Meditation Society was launched in Germany in 1965 after 18 teaching centers had been established. In 1966–1967 the number of teaching centers increased to 35 and the society opened an "academy" in Bremen-Blumenthal.[33][page needed]

In 2000, the Maharishi group launched the IT company Cosmic InfoTech solutions.[sic][293] The Maharishi Group Venture was reported in 2006 to be "a non-profit, benevolent society based in India that aids students".[294] According to his bio at the Human Dimensions web site, Anand Shrivastava is the "chairmen and managing director of the Maharishi Group of Companies".[295] According to the web sites of Picasso Animation College and Maharishi Ayurveda Products Ltd. the "Maharishi Group is a multinational and multidimensional conglomerate with presence in over 120 countries".[sic][296][297] "In India, Maharishi organization is engaged in multifarious activities including education, health, technology development and social welfare. Maharishi Group is a multinational and multidimensional conglomerate with presence in over 120 countries." According to a report in Global Solar Technology, the Maharishi Group is "India's leading International group with diversified interests".[277] A company called Maharishi Renewable Energy Ltd (MREL) was reported in 2009 to be "part of $700 million Maharishi group".[298][299]

In 2008, a resident of Maharishi Vedic City, Iowa filed a lawsuit against the India based company, Maharishi Ayurveda Products Pvt Ltd. (MAPPL), alleging that she had received lead poisoning from one of their products which she had purchased on a trip to India.[300][301][302]

The Institute for Fitness and Athletic Excellence is the American organization that offers the TM program to amateur and professional athletes.[187] The Global Mother Divine Organization describes itself as "an international non-profit organization that offers women" the "Transcendental Meditation technique and its advanced programs."[303]

The World Center for Ayurveda was founded in India in 1985. Other active organizations include the Institute For Social Rehabilitation and the International Center for Scientific Research.[173]

Maharishi Information Technology Pvt. Ltd. (MITPL) was founded in 1999.[304]

Marketing

[edit]The public presentation of the TM technique has varied over its 50 year history. Some authors have praised its methods and success while others have criticized its marketing techniques. For example author G. Francis Xavier writes, the Maharishi is "one of the best salesman" and has made full use of the mass media to propagate TM around the world[305] while authors Bainbridge and Stark criticize the TM movement for using endorsements from the scientific establishment as "propaganda", reprinting favorable articles and using positive statements by government officials in conjunction with their publicity efforts.[306] On the other hand, cardiologist Stephen Sinatra and professor of medicine Marc Houston have said of the Maharishi: "His emphasis on scientific research proved that the timeless practice of meditation was not just an arcane mystical activity for Himalayan recluses, but rather a mind-body method hugely relevant to and beneficial for modern society".[307]

History

[edit]According to one account, the Maharishi in 1959 began "building an infrastructure" using a "mass marketing model" for teaching the TM technique to Westerners.[308] First, the Maharishi visited the U.S. because he felt that its people were ready to try something new, and the rest of the world would then "take notice".[309] By the same token, author Philip Goldberg says the Maharishi's insistence that TM was easy to do was not a "marketing ploy", but rather "a statement about the nature of the mind."[309] In 1963 the Maharishi published his first book on Transcendental Meditation called The Science of Being and Art of Living. In the mid-1960s, the TM organization began presenting its meditation to students via a campaign led by a man named Jerry Jarvis who had taken the TM course in 1961.[309] By 1966, the Students Meditation Society (SIMS) had begun programs in U.S. colleges such as University of California, Berkeley, Harvard, Yale and others, and was a "phenomenal success".[309][310]

In the late 1960s, the TM technique received "major publicity" through its associations with The Beatles, and by identifying itself with various aspects of modern day counterculture.[311][312] However, Goldberg and others say that during the first decade of the TM organization, the Maharishi's main students in the West were not rock stars and their fans, but ordinary, middle-aged citizens. In the late 60's, young people coming to learn TM at the center in London, England, were surprised "to be greeted not by fellow hippies but by the proper, middle-aged men and women who were Maharishi's earliest followers."[313][314] Another author notes that, "By the time the Beatles first met the Maharishi Mahesh Yogi in London in 1966, Mahesh had already made seven trips around the globe, established 38 centres, and amassed more than 100,000 followers."[315]

While Lennon and Harrison were in India in 1968 there were tensions with the Maharishi over business negotiations for a proposed documentary film and television show. The Beatles were surprised to find the Maharishi was a sophisticated negotiator[316] with an interest in publicity, business and finances.[317]

TM is said to have taken full advantage of all available publicity, and began to market to specific populations, such as spiritual people, political people and "pragmatic" self-help people. The latter approach is said to have been "given impetus" by the scientific research on the technique.[20] In The Future of Religion, sociologists Bainbridge and Stark write that, while the movement attracted many people through endorsements from celebrities such as The Beatles, another marketing approach was "getting articles published in scientific journals, apparently proving TM's claims or at least giving them scientific status".[306] In the 1970s, according to Philip Goldberg, the Maharishi began encouraging research on the TM technique because he felt that hard scientific data would be a useful marketing tool and a way to re-brand meditation as a scientific form of deep rest, rather than a mystical "samadhi"; one of his first steps in secularizing the technique.[309] The Maharishi's "appropriation of science was clearly part of his agenda from the beginning" says Goldberg, and so his "organization was incorporated as an educational non-profit, not a religious one".[309] The Maharishi asked people with marketing expertise, like SIMS president, Jarvis, to present TM as a method for inner peace and relaxation based on scientific proof [318] and, because the TM technique was the first type of meditation to undergo scientific testing, it "has always received the most publicity".[308]

The first peer-reviewed research on TM, conducted by physiologist Robert K. Wallace at UCLA, appeared in the journal Science in 1970. It attracted significant public and scientific attention. The study's findings were also published in the American Journal of Physiology in 1971, in Scientific American in 1972,[319] and reported in Time magazine in 1971.[320] Between mid-1970 and 1974, the number of research institutions conducting research on TM grew from four to over 100.[321]

Several researchers have said that Maharishi's encouragement of research on TM resulted in a beneficial increase in the scientific understanding of not only TM but of meditation in general, resulting in the increased use of meditation to alleviate health problems and to improve mind and body.[307] Neuroscientists Ronald Jevning and James O’Halloran wrote in 1984 that "The proposal of the existence of a unique or fourth state of consciousness with a basis in physiology" by the Maharishi in 1968 was "a major contribution to the study of human behavior" resulting in "a myriad of scientific studies both basic and applied in an area heretofore reserved for ‘mysticism'."[322] Research reviews of the effects of the Transcendental Meditation technique have yielded results ranging from inconclusive[100][323][324][325] to clinically significant.[326][327][328][329][330] Newsweek science writer Sharon Begley said that "the Maharishi deserves credit for introducing the study of meditation to biology. Hospitals from Stanford to Duke have instituted meditation programs to help patients cope with chronic pain and other ailments."[331]

According to Bainbridge and Stark, TM had engaged in several mass media campaigns prior to 1973, and had received a great amount of publicity, but the main source of new TM students was word of mouth, or the "advice of friends", because "TM was a relatively cheap, short-term service, requiring no deep commitment".[332] Author Jack Forem agrees, and writes: "the main source of publicity for the movement has been satisfied practitioners spreading the news by word of mouth".[333]

In 1973, Maharishi International University (MIU) faculty member, Michael Peter Cain co-wrote a book with Harold Bloomfield and Dennis T. Jaffe called TM: Discovering Inner Energy and Overcoming Stress. The TM movement's area coordinator, Jack Forem, published his book Transcendental Meditation, Maharishi Mahesh Yogi and the Science of Creative Intelligence in 1976.[333] That year, TM teacher, Peter Russell, released his book An Introduction to Transcendental Meditation and the Teachings of Maharishi Mahesh Yogi as did MIU board of trustees member, Nat Goldhaber who wrote TM: An alphabetical guide to the transcendental meditation program. The Maharishi made appearances on the Merv Griffin Show in 1975 and again in 1977.[334][335][336] TM teacher, George Ellis published a book called Inside Folsom Prison: Transcendental Meditation and TM-Sidhi Program in 1983. Movement spokesman, Robert Roth, published his book, TM: Transcendental Meditation: A New Introduction to Maharishi's Easy, Effective and Scientifically Proven Technique in 1988. As of 1993 the organization was utilizing its own public relations office called the Age of Enlightenment News Service.[337] In a scene in the 1999 film, Man on the Moon, TM meditator Andy Kaufman was asked to leave a TM teacher training course because his performances were incompatible with the behavior expected of a TM teacher.[338] The Maharishi gave his first interview in 25 years on the Larry King Show in May 2002. Additional books were published by Maharishi University of Management (MUM) faculty and researchers such as David Orme-Johnson's Transcendental Meditation in Criminal Rehabilitation and Crime Prevention in 2003 and Robert Scheider's Total Heart Health: How to Prevent and Reverse Heart Disease with the Maharishi Vedic Approach to Health in 2006.

According to the New York Times, since 2008 there has been an increased number of celebrity endorsements for Transcendental Meditation. Those who have appeared at promotional events to raise funds to teach TM to students, veterans, prisoners and others include comedian/actor Russell Brand, TV host/physician Mehmet Oz, and singer Moby.[339] A benefit performance in New York City in 2009 included a reunion performance by musicians Paul McCartney and Ringo Starr, Donovan, Sheryl Crow, Eddie Vedder, Bettye LaVette, Ben Harper, Paul Horn, and Mike Love. Others appearances included comedian Jerry Seinfeld, actress Laura Dern, and radio talk show host Howard Stern.[340] The book Transcendence: Healing and Transformation Through Transcendental Meditation was published by psychiatrist Norman Rosenthal in 2011[341] and MUM faculty member Fred Travis published Your Brain is a River, Not a Rock in 2012. A jazz concert to benefit the David Lynch Foundation was held in New York City in 2013. The events included remarks by TV hosts Mehmet Oz, George Stephanopoulos and actress Liv Tyler with musical performances by Herbie Hancock, Corrine Bailey Rae and Wynton Marsalis.[342]

Reception to Marketing

[edit]In 1988, author J. Isamu Yamamoto wrote that "TM was called the McDonald's of meditation because of its extravagantly successful packaging of Eastern Meditation for the American mass market".[318] According to the 1980 book, TM and Cult Mania, scientists associated with TM have attempted to prove the Maharishi's concepts by uniting scientific data and mystical philosophy.[18] The 2010 book, Teaching Mindfulness, says that TM's eventual success as a new social movement was based on the "translation in Western language and settings, popular recognition, adoption within scientific research in powerful institutions." The book goes on to say that TM's "use of sophisticated marketing and public relations techniques, represents a model for success in the building of new social movements".[20][308] Sociologist Hank Johnston, who analyzed TM as a "marketed social movement" in a 1980 paper, says that TM has used sophisticated techniques, such as tailored promotional messages for different audiences, and pragmatically adapted them to different cultures and changing times. Johnston says that TM's "calculated strategies" have led to its "rapid growth". In particular, it has objectified the rank-and-file membership, marketed the movement as a product, and created a perception of grievances for which it offers a panacea.[343] In her book, The Field, author Lynne McTaggart notes that the "organization has been ridiculed, largely because of the promotion of the Maharishi's own personal interests", but suggests that "the sheer weight of data...[on the Maharishi Effect]...is compelling".[344] According to an article in The Independent, despite early criticism, the TM technique has moved from margin to mainstream, due mostly to its "burgeoning body of scientific research". Its recent appeal seems due to the possibility of relaxation with no chemical assistance.[345] Jerrold Greenberg in his book Comprehensive Stress Management writes that the Maharishi was a "major exporter of meditation to the Western world" who "developed a large, worldwide, and highly effective organization to teach Transcendental Meditation". Greenberg goes on to say that "the simplicity of this technique, coupled with the effectiveness of its marketing by TM organizations quickly led to its popularity."[346] According to Goldberg, research and meditation in general are likely to be the Maharishi's "lasting legacy".[309]

Criticism and evaluation

[edit]Purity of the Maharishi's teaching

[edit]The Maharishi believed that in order to maintain the continuity of Transcendental Meditation it had to be taught by trained teachers in dedicated centers.[347] Maharishi recorded his lectures; systematized the teaching of the technique, insisted the technique not be mixed with other techniques and separated the technique from other points of view and practices that might confuse its understanding.[348] He said that the "purity of the system of meditation" must be maintained "at any cost because the effect lies in the purity of the teaching".[347] TM practitioners that are suspected of interacting with other gurus can be banned from meditations and lose other privileges.[349] In the 1990s, Maharishi prohibited his students from interacting with Deepak Chopra.[350] As a result, Lowe writes, the number of sufficiently orthodox practitioners was significantly reduced by 2007.[349] In 1983, Robin Wadsworth Carlson began teaching his meditation program via a "World Teacher Seminar." Many students at Maharishi International University (MIU) were suspended after describing the literature promoting the seminar. In response Carlson filed a lawsuit against MIU alleging interference in conducting his seminars.[351]

New religious movement

[edit]George Chryssides identifies the TM movement as one of the new religious movements "which lacks overtly religious features as traditionally understood" and whose focus is on human potential. He also describes the TM movement in terms of Roy Wallis's typological terms as a world affirming rather than world renouncing or world accommodating new religious movement.[352] According to religious studies scholar, Tamar Gablinger, the "complex structure" of the TM organization falls somewhere between being a commercial entity and a religious and social movement. Gablinger says this allows sociologists to categorize it in a variety of ways.[33][page needed] Both Gablinger and sociologist Hank Johnston describe the TM organization as a "marketed social movement."[33][page needed][343]

Connections to Hinduism

[edit]| Part of a series on |

| Hinduism |

|---|

|

Author Noretta Koertge asserts that the TM movement introduced to the West the "scientistic version of Hinduism"; the idea that "the Vedas are simply another name for science".[353] The TM movement has been described by Neusner as being a neo-Hindu adaptation of classical Vedantic Hinduism,[354][355] while author Gerald James Larson says it retains "only shallow connections" to Hinduism.[356]

Critics charge that the TM movement is a bastardized form of Hinduism which denies its religious roots and claims a scientific basis for the purpose of securing government funding for its programs.[357] In their book, Millennium, Messiahs and Mayhem: Contemporary Apocalyptic Movements, Robbins and Palmer refer to the Maharishi's teaching that the practice of Transcendental Meditation will bring Ram Rajya (the rule of God) on earth as a form of progressive millennialism from the Hindu tradition.[358]

Cult, sect, religion

[edit]Along with other movements that developed as part of the hippie subculture in the 1960s, there has been debate on "cult"-like aspects of the Transcendental Meditation movement.[18] Camille Paglia wrote that TM was the "major Asian cult" of the 1960s.[23] The Israeli Center for Cult Victims also considers the movement to be a cult.[24] Maharishi University says that it is not a religious institution but people who have left the movement refer to it as a cult which requires "deprogramming" for former members.[25]

In 1987, the Cult Awareness Network (CAN) held a press conference and demonstration in Washington, D.C., saying that the organization that teaches the Transcendental Meditation technique "seeks to strip individuals of their ability to think and choose freely." Steven Hassan, an author on the topic of cults, and at one time a CAN deprogrammer, said at the press conference that members display cult-like behaviors, such as the use of certain language and particular ways of dressing. TM teacher and spokesperson, Dean Draznin, "discounted CAN's claims" saying that Transcendental Meditation "doesn't involve beliefs or lifestyle" or "mind control" and "We don't force people to take courses". Another spokesperson, Mark Haviland of the related College of Natural Law said that TM is "not a philosophy, a life style or a religion."[359]

Author Shirley Harrison says that the method of recruitment is one sign that helps to identify cult, and that TM's only method is advertising. She also says that "none of the other 'cultic qualities' defined by cultwatchers can be fairly attributed to TM."[360] Harrison writes that the Maharishi's teaching does not require conversion and that Transcendental Meditation does not have a religious creed.[361][page needed]

In the book Cults and New Religions, Cowan and Bromley write that TM is presented to the public as a meditation practice that has been validated by science but is not a religious practice nor is it affiliated with any religious tradition. They say that "although there are some dedicated followers of TM who devote most or all of their time to furthering the practice of Transcendental Meditation in late modern society, the vast majority of those who practice do so on their own, often as part of what has been loosely described as the New Age Movement. "[362] They say that most scholars view Transcendental Meditation as having elements of both therapy and religion, but that on the other hand, "Transcendental Meditation has no designated scripture, no set of doctrinal requirements, no ongoing worship activity, and no discernible community of believers." They also say that Maharishi didn't claim to have special divine revelation or supernatural personal qualities.[363][page needed]

Marc Galanter, writes in his book Cults: Faith, Healing and Coercion that TM "evolved into something of a charismatic movement, with a belief system that transcended the domain of its practice". He notes how a variety of unreasonable beliefs came to be seen as literally true by its "more committed members". He cites an "unlikely set of beliefs" that includes the ability to levitate and reduce traffic accidents and conflicts in the Middle East through the practice of meditation.[364]

In his book Soul snatchers: the mechanics of cults, Jean-Marie Abgrall describes how Altered States Of Consciousness (ASCs) are used in many cults to make the initiate more susceptible to the group will and world view. He cites research by Barmark and Gautnitz which showed the similarities between the states obtained by Transcendental Meditation and ASCs.[365] In this way, not only does the subject become more reliant on the ASC, but it allows for a weakening of criticism of the cult and increase in faith therein. Abgrall goes on to note that the use of mantras is one of the most widespread techniques in cults, noting in TM this mantra is produced mentally.[366] He says that a guru is usually central to a cult and that its success will rely on how effective that guru is. Among the common characteristics of a guru he notes paraphrenia, a mental illness that completely cuts the individual from reality. In regard to this he notes for example, that the Maharishi recommended the TM-Sidhi program including 'yogic flying' as a way to reduce crime.[367]

In his book The Elementary Forms of The New Religious Life, Roy Wallis writes in the chapter called "Three Types of New Religious Movements" that TM is a "world affirming new religion which does not reject the world and its organisation" [sic]. Wallis goes on to say that "no rigorous discipline is normally involved" and "no extensive doctrinal commitment is entailed, at least not at the outset". Likewise, he writes, "No one is required to declare a belief in TM, in the Maharishi or even in the possible effects of the technique".[368] In a later chapter called "The Precariousness of the Market", he writes that TM meditators are "expected to employ the movement's rhetoric and conceptual vocabulary" and shift from an empirical product [the Transcendental Meditation technique] to a "system of belief and practice" [such as the TM Sidhi program] and in this way "the movement shifts from cult towards sect".[369] Sociologist Alan E. Aldridge writes that Transcendental Meditation fits Roy Wallis' definition of a "world-affirming religion". According to Aldridge, TM has an ethos of "individual self-realization" and "an inner core of committed members" who practice more advanced techniques (the TM-Sidhi program) that may not even be known to the "ordinary consumer of TM".[370]

Reporter Michael D'Antonio wrote in his book, Heaven on Earth – Dispatches from America's Spiritual Frontier that, as practiced at Maharishi International University, Transcendental Meditation is "a cult rather than a culture".[371] D'Antonio wrote that Transcendental Meditation was like the worst of religion: rigid, unreasonable, repressive, and authoritarian, characterized by overt manipulation, a disregard for serious scholarship, and an unwillingness to question authority. For the first time in his travels he found people he believed to be truly deluded, and a physics department teaching theories that were dead wrong.[372] D'Antonio charges that they have taken Transcendental Meditiation and transformed it "into a grandiose narcissistic dream, a form of intellectual bondage, that they call enlightenment".[373]

Clarke and Linzey argue that for the ordinary membership of TM their lives and daily concerns are little — if at all — affected by its cult nature. Instead, it is only the core membership who must give total dedication to the movement.[374] A former TM teacher, who operates an online site critical of TM, says that 90 percent of participants take an introductory course and "leave with only a nice memory of incense, flowers, and smiling gurus" while "the 10 percent who become more involved". He says those participants encounter "environments where adherents often weren't allowed to read the news or talk to family members".[357] Another former TM Movement member, says there were "times when devotees had their mail screened and were monitored by a Vigilance Committee".[citation needed]

Religious scholar Tamar Gablinger notes that some of the reports from "apostates and adversaries" who have written about their involvement with the TM movement are "rather biased."[33][page needed]

Bibliography

[edit]- Cowan, Douglas E.; Bromley, David G. (2007). Cults and New Religions: A Brief History (Blackwell Brief Histories of Religion). Wiley-Blackwell. ISBN 978-1-4051-6128-2.

- Forsthoefel, Thomas A.; Humes, Cynthia Ann (2005). Gurus in Americ. Albany, New York: State University of New York Press. ISBN 978-0-7914-6573-8.

- Freeman, Lyn (2009). Mosby's Complementary & Alternative Medicine: A Research-Based Approach. Mosby Elsevier. ISBN 9780323053464.

- Gablinger, Tamar (2010). The Religious Melting Point: On Tolerance, Controversial Religions and the State : The Example of Transcendental Meditation in Germany, Israel and the United States. Language: English. Tectum. ISBN 978-3-8288-2506-2.

- Harrison, Shirley (1990). Cults: The Battle for God. Kent: Christopher Helm.

- Wallis, Roy (1984). The elementary forms of the new religious life. London: Routledge; Boston: Kegan Paul. ISBN 978-0-7100-9890-0.

References

[edit]- ^ a b Stark, Rodney and Bainbridge, William Sims (1985) University of California Press, The Future Of Religion, page 287 "Time magazine in 1975 estimated that the U.S. total had risen to 600,000 augmented by half that number elsewhere" =[900,000 world wide] "Annual Growth in TM Initiations in the U.S. [chart] Cumulative total at the End of Each Year: 1977, 919,300"

- ^ a b Petersen, William (1982). Those Curious New Cults in the 80s. New Canaan, Connecticut: Keats Publishing. p. 123. ISBN 9780879833176. claims "more than a million" in the United States and Europe.

- ^ a b Occhiogrosso, Peter. The Joy of Sects: A Spirited Guide to the World's Religious Traditions. New York: Doubleday (1996); p 66, citing "close to a million" in the United States.

- ^ a b Bainbridge, William Sims (1997) Routledge, The Sociology of Religious Movements, page 189 "the million people [Americans] who had been initiated"

- ^ a b Analysis: Practice of requiring probationers to take lessons in transcendental meditation sparks religious controversy, NPR All Things Considered, 1 February 2002 | ROBERT SIEGEL "TM's five million adherents claim that it eliminates chronic health problems and reduces stress."

- ^ a b Martin Hodgson, The Guardian (5 February 2008) "He [Maharishi] transformed his interpretations of ancient scripture into a multimillion-dollar global empire with more than 5m followers worldwide"

- ^ Stephanie van den Berg, Sydney Morning Herald, Beatles guru Maharishi Mahesh Yogi dies, (7 February 2008) "the TM movement, which has some five million followers worldwide"

- ^ Meditation a magic bullet for high blood pressure – study, Sunday Tribune (South Africa), (27 January 2008) "More than five million people have learned the technique worldwide, including 60,000 in South Africa."

- ^ a b c Maharishi Mahesh Yogi – Transcendental Meditation founder's grand plan for peace, The Columbian (Vancouver, WA), 19 February 2006 | ARTHUR MAX Associated Press writer "transcendental meditation, a movement that claims 6 million practitioners since it was introduced."

- ^ Bickerton, Ian (8 February 2003). "Bank makes an issue of mystic's mint". Financial Times. London (UK). p. 9. the movement claims to have five million followers,

- ^ a b Maharishi Mahesh Yogi, Spiritual Leader Dies, New York Times, By LILY KOPPEL, Published: 6 February 2008 "Since the technique's inception in 1955, the organization says, it has been used to train more than 40,000 teachers, taught more than five million people."

- ^ Sharma & Clark 1998, Preface

- ^ a b c Welvaert, Brandy (5 August 2005). "Vedic homes seek better living through architecture" (PDF). Rock Island Argus. Retrieved 24 January 2013.

- ^ a b Spivack, Miranda (12 September 2008). "Bricks Mortar and Serenity". Washington Post. Retrieved 13 February 2013.

- ^ a b "Maharishi Mahesh Yogi". The Times. London (UK). 7 February 2008. Archived from the original on 24 May 2010. Retrieved 13 February 2013.

- ^ "Maharishi Mahesh Yogi". Britannica Concise Encyclopedia. Retrieved 13 February 2013.

- ^ For new religious movement see:

Beckford, James A. (1985). Cult Controversies: The Societal Response to New Religious Movements. Tavistock Publications. p. 23. ISBN 978-0-422-79630-9. Retrieved 12 February 2013.

Parsons, Gerald (1994). The Growth of Religious Diversity: Traditions. The Open University/Methuen. p. 288. ISBN 978-0-415-08326-3. Retrieved 12 February 2013.

For neo-Hindu, see:

Alper, Harvey P. (December 1991). Understanding Mantras. Motilal Banarsidass Publ. p. 442. ISBN 978-81-208-0746-4. Retrieved 12 February 2013.

Raj, Selva, J.; Harman, William, P. (2007). Dealing With Deities: The Ritual Vow in South Asia. SUNY Press. p. 129. ISBN 978-0-7914-6708-4. Retrieved 12 February 2013.{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b c d Persinger, Michael A.; Carrey, Normand J.; Suess, Lynn A. (1980). TM and Cult Mania. North Quincy, Massachusetts: Christopher Pub. House. ISBN 978-0-8158-0392-8.

- ^ Dawson, Lorne L. (2003) Blackwell Publishing, Cults and New Religious Movements, Chapter 3: Three Types of New Religious Movement by Roy Wallis (1984), page 44-48

- ^ a b c Christian Blatter, Donald McCown, Diane Reibel, Marc S. Micozzi, (2010) Springer Science+Business Media, Teaching Mindfulness, Page 47

- ^ Olson, Carl (2007) Rutgers University Press, The Many Colors of Hinduism, page 345

- ^ Shakespeare, Tom (24 May 2014). "A Point of View". BBC News. BBC. Retrieved 31 May 2014.

- ^ a b Paglia, Camille (Winter 2003). "Cults and Cosmic Consciousness: Religious Visions in the American 1960s". Arion. Third. 10 (3). Boston University: 57–111 [76]. JSTOR 20163901.

- ^ a b "Women's tragedy – Haaretz – Israel News". Haaretz.

- ^ a b Depalma, Anthony (29 April 1992). "University's Degree Comes With a Heavy Dose of Meditation (and Skepticism)". The New York Times. Retrieved 28 March 2010.

- ^ "the TM technique does not require adherence to any belief system—there is no dogma or philosophy attached to it, and it does not demand any lifestyle changes other than the practice of it."

- ^ "Its proponents say it is not a religion or a philosophy."The Guardian 28 March 2009

- ^ "It's used in prisons, large corporations and schools, and it is not considered a religion." Archived 3 March 2016 at the Wayback Machine Concord Monitor

- ^ Chryssides, George. "Defining the New Spirituality". Cesnur. Retrieved 12 February 2013.

One possible suggestion is that religion demands exclusive allegiance: this would ipso facto exclude Scientology, TM and the Soka Gakkai simply on the grounds that they claim compatibility with whatever other religion the practitioner has been following. For example, TM is simply – as they state – a technique. Although it enables one to cope with life, it offers no goal beyond human existence (such as moksha), nor does it offer rites or passage or an ethic. Unlike certain other Hindu-derived movements, TM does not prescribe a dharma to its followers – that is to say a set of spiritual obligations deriving from one's essential nature.

- ^ Olson, Helena, Roland (March 2007). His Holiness Maharishi Mahesh Yogi: A Living Saint for the New Millennium: Stories of His First Visit to the USA. Samhita Productions. p. 297. ISBN 978-1-929297-21-4.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b Oates, Robert (2006). Celebrating the Dawn: Maharishi Mahesh Yogi and the TM technique. Putnam. p. 40. ISBN 978-0-399-11815-9.

- ^ a b c d Koppel, Lily (6 February 2008). "Maharishi Mahesh Yogi, Spiritual Leader, Dies – New York Times". The New York Times. Retrieved 26 May 2010.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l Gablinger 2010.

- ^ DART, JOHN (29 October 1977). "TM Ruled Religious, Banned in Schools". Los Angeles Times. p. 29.

- ^ Stephanie van den Berg, Sydney Morning Herald, Beatles guru Maharishi Mahesh Yogi dies, (7 February 2008) "the TM movement, which has some five million followers worldwide"

- ^ Meditation a magic bullet for high blood pressure – study, Sunday Tribune (South Africa), (27 January 2008) "More than five million people have learned the technique worldwide, including 60,000 in South Africa."

- ^ Bickerton, Ian (8 February 2003). "Bank makes an issue of mystic's mint". Financial Times. London (UK). p. 9.

- ^ Financial Times (2003), 5 million, Bickerton, Ian (8 February 2003). "Bank makes an issue of mystic's mint". Financial Times. London (UK). p. 9.; Asian News International (2009), 4 million "David Lynch to shoot film about TM guru Maharishi Mahesh Yogi in India". The Hindustan Times. New Delhi. Asian News International. 18 November 2009.

- ^ Hecht, Esther (23 January 1998). "Peace of Mind". Jerusalem Post. p. 12.