Little Saint Hugh of Lincoln

Hugh of Lincoln | |

|---|---|

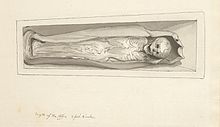

The body of Hugh in its coffin, drawn by Samuel Hieronymus Grimm (1791) | |

| Born | 1246 |

| Died | Before 27 August 1255 (aged 8–9) |

| This is a part of the series on |

| History of the Jews in England |

|---|

| Medieval |

| Blood libel in England |

| Medieval Jewish buildings |

| Modern |

| Related |

Hugh of Lincoln (1246 – 27 August 1255) was an English boy whose death in Lincoln was falsely attributed to Jews. He is sometimes known as Little Saint Hugh or Little Sir Hugh to distinguish him from the adult saint, Hugh of Lincoln (died 1200). The boy Hugh was not formally canonised, so "Little Saint Hugh" is a misnomer.[a]

Hugh became one of the best known of the blood libel "saints": generally Christian children whose deaths were interpreted as Jewish human sacrifices. It is believed by some historians that the church authorities of Lincoln steered events in order to establish a profitable flow of pilgrims to the shrine of a martyr and saint.[3]

Hugh's death is significant because it was the first time that the Crown gave credence to ritual child murder allegations, through the direct intervention of King Henry III.[4] It was further bolstered by Matthew Paris' account of the events, and by Edward I's support for the cult after his ordering of the expulsion of Jews from England, particularly his projection of power through the renovation of the tomb in the style of the Eleanor crosses.[5]

As a result, in contrast to other English blood libels, the story entered the historical record, medieval literature and in ballads that circulated until the twentieth century.[5]

Background

Allegations of ritual child murder had become increasingly common following the circulation of The Life and Miracles of St William of Norwich by Thomas of Monmouth, the hagiography of William of Norwich, a child-saint said to have been crucified by Jews in 1144. Other accusations followed, such as that of Harold of Gloucester (1168) and Robert of Bury (1181). The story of William and similar rumours influenced the myth that developed around Hugh. The accusations may have been promoted by church officials hoping to establish local cults to attract pilgrims and donations.

During the years running up to the accusation, King Henry III taxed English Jews heavily. This in turn forced Jewish moneylenders to ensure their debts were paid, with no flexibility, or to sell their debt bonds to Christians. The King's relatives and courtiers in particular would buy debt bonds, with the intention to seize the debtors' property as collateral. These policies of King Henry would later provoke the Second Barons' War.

Church restrictions against Jews also built up in the period. Pronouncements were made by the Vatican ordering that Jews live separate from Christians, that Christians were not to work for Jews, especially in their homes, and that Jews were to wear yellow badges to identify themselves. Church pronouncements in particular led to a number of English towns expelling their Jewish communities. Henry III codified most of the Church's demands and put them into enforceable law in his 1253 Statute of Jewry.[b]

At the time of the Hugh of Lincoln murder accusations, Henry III had sold his rights to tax English Jews to his brother, Richard, Earl of Cornwall. The King decreed that if any Jew were convicted of a crime, his money and property would then be forfeit to the Crown.

A number of Jews from across England had gathered in Lincoln to attend a wedding at the time of the child's death.[4]

The accusation and myth

The nine-year-old Hugh disappeared on 31 July, and his body was discovered in a well on 29 August. It was claimed that Jews had imprisoned Hugh, during which time they tortured and eventually crucified him. It was said that the body had been thrown into the well after attempts to bury it failed, when the earth had expelled it.[7]

The chronicler Matthew Paris described the supposed murder, implicating all the Jews in England:

This year [1255] about the feast of the apostles Peter and Paul [27 July], the Jews of Lincoln stole a boy called Hugh, who was about eight years old. After shutting him up in a secret chamber, where they fed him on milk and other childish food, they sent to almost all the cities of England in which there were Jews, and summoned some of their sect from each city to be present at a sacrifice to take place at Lincoln, in contumely and insult of Jesus Christ. For, as they said, they had a boy concealed for the purpose of being crucified; so a great number of them assembled at Lincoln, and then they appointed a Jew of Lincoln judge, to take the place of Pilate, by whose sentence, and with the concurrence of all, the boy was subjected to various tortures. They scourged him till the blood flowed, they crowned him with thorns, mocked him, and spat upon him; each of them also pierced him with a knife, and they made him drink gall, and scoffed at him with blasphemous insults, and kept gnashing their teeth and calling him Jesus, the false prophet. And after tormenting him in diverse ways they crucified him, and pierced him to the heart with a spear. When the boy was dead, they took the body down from the cross, and for some reason disembowelled it; it is said for the purpose of their magic arts.[8][c]

While the Paris account is significant as the most famous and influential version of the myth, due to his own popularity as a chronicler and talent as storyteller, it is also thought to be the least reliable, and most fabricated, of the contemporary accounts of what had supposedly taken place.[9] Other contemporary accounts include the Annals of Waverley and of Burton Abbey.[10]

Role of the Bishop

A Jew, Copin, reportedly confessed to the murder. He was also offered immunity from sentencing in return for his confession according to contemporary accounts.[11] Copin appears to have been interrogated under torture by John of Lexington, brother of Henry, the new Bishop of Lincoln, and servant of the King.[12] This leads to the conclusion by modern historians that there was likely clerical collusion to give credence to the accusation, with the aim of profiting from a new cult with pilgrims and their gifts.[13]

Royal intervention

A number of circumstances exacerbated the impact of this event.[8] Henry III arrived in Lincoln around a month after the initial arrest and confession. He ordered Copin to be executed, and for ninety Jews to be arrested at random in connection with Hugh's disappearance and death and held in the Tower of London. They were charged with ritual murder. Eighteen of the Jews were hanged for refusing to participate in the proceedings, claiming this was a show trial and refusing to throw themselves on the mercy of a Christian jury.[9] Gavin I. Langmuir says:

What distinguished the Lincoln affair from other accusations of ritual murder was that the king took personal cognizance and had one Jew executed immediately and eighteen others spectacularly executed later. That royal substantiation of the truth of the charge was probably decisive for Hugh's fame, which far outshadowed that of William of Norwich, Harold of Gloucester, Robert of Bury St. Edmunds, and the poor anonymous infant of St. Paul's.[14]

Garcias Martini, knight of Toledo, interceded for the release of Benedict son of Moses of London, probably the father of Belaset, whose wedding had been taking place. In January a further pardon was extended to a Christian Jew, John, after the intervention of a Dominican friar.[15] A trial took place on 3 February at Westminster for the remaining 71 prisoners. They were condemned to death by a jury of 48. After this point either the Dominicans or Franciscans interceded, together with Richard of Cornwall. By May, the prisoners were released. It may be that doubt as to their guilt had set in, as it is unlikely that the monks or Richard would have interceded without thinking the charge was false, given the severity of the charge.[16]

The difficulty remains as to why King Henry and his servant John of Lexington would have believed the accusations in the first place. For Lexington, his motivations may be his personal connections to the clerics of Lincoln, including his brother the Bishop, who stood to benefit from the veneration of the 'martyr' Hugh. He may have believed, or wished to believe, what he heard. While the decision to act belonged to the King, Langmuir believes that he was weak and easily manipulated by Lexington. Langmuir says Henry III has been described as; "a suspicious person who flung charges of treason recklessly, [who] was credulous and poor in judgment, and often appeared like a petulant child. When to these qualities we add his addiction to touring the shrines of England, it becomes easier to understand why he acted as he did, both when he heard Copin's confession and when the friars and cooler heads intervened later."[17] Langmuir therefore concludes that Lexington "incited the weakly credulous Henry III to give the ritual murder fantasy the blessing of royal authority".[18] Jacobs on the other hand sees the financial benefits that Henry received as a major factor, conscious or unconscious, in his decision to arrest en masse and execute Jews. As noted above, he had mortgaged his income from the Jews to Richard of Cornwall, but was still entitled to the property of any Jew executed, adding that Henry, "like most weak princes, was cruel to the Jews".[19]

Veneration

After news spread of his death, miracles were attributed to Hugh; and he became one of the youngest individual candidates for sainthood, with 27 July unofficially made his feast day. Many local 'saints' of the medieval period were not canonised but were locally dubbed saints and venerated. 'Little Saint Hugh' was for a while acclaimed as a saint by local people but never officially recognised as one.[20] Over time, the issue of the rush to sainthood was raised, and Hugh was never canonised[21] and was never a part of the official Catholic calendar of saints. The Vatican never included the child Hugh in Catholic martyrology and his traditional English feast day is not celebrated.[22]

Lincoln Cathedral benefited from the episode; Hugh was regarded as a Christian martyr, and sites associated with his life became objects of pilgrimage.[7]

The shrine dated to the period immediately after the expulsion of the Jews from England in 1290, partly funded by Edward I, as a propaganda tool helping to justify his actions by emphasising the danger that Jews supposedly posed to Christians. The royal coat of arms was prominently displayed.[23] As Stacey notes: "A more explicit identification of the crown with the ritual crucifixion charge can hardly be imagined."[24] The design included decoration commemorating Edward I's wife Eleanor of Castile, who had been widely disliked for large-scale buying and selling of Jewish bonds, with the aim of requisitioning the lands and properties of those indebted;[25] it may have deliberately echoed that of the Eleanor crosses, also commemorating her.[26] This intervention was a major "propaganda coup" rehabilitating Edward and Eleanor's image and claiming credit for the Expulsion.[27]

While popular into the 1360s, the cult seems to have declined in the next half century, as it was raising just 10½d. in 1420–21.[28] The shrine was largely destroyed after the English Reformation. During the Cathedral restoration of 1790 a stone coffin, 3 feet 3 inches (1 metre) long, was found containing the skeleton of a boy; this was drawn by Samuel Hieronymus Grimm.

Legacy and significance

The myth of ritual child murder was a continuing theme in anti-semitism and long-standing in English culture.[29] The Hugh story is referenced by Geoffrey Chaucer's Canterbury Tales in The Prioress's Tale. Christopher Marlowe also apparently refers to the story in The Jew of Malta, where Friar Jacomo at the end of Act Three asks of a Jew, "What, has he crucified a child?"[30] Again, Marlowe may have known the story through Paris's account. The story is retold as fact in Thomas Fuller's 1662 Worthies of England.[31][d]

Ballads referring to the incident circulated in England, Scotland and France.[32] The earliest English and French versions appear to have been composed near the time.[33] The "Sir Hugh" ballad went through many variations, and was still well known into the nineteenth and twentieth century, when versions could be found in the United States.

Langmuir describes the fantasy concocted by Lexington as contributing to some of the darkest strands of anti-Jewish prejudice. Lexington:

inspired Matthew Paris to write a vivid garbled yarn that would ring in men's minds for centuries and blind modern historians. A century and a half later, Geoffrey Chaucer, after letting the legend of the singing boy slip from the prioress's lips, would inevitably be reminded of England's most famous proof of Jewish evil and conclude with an invocation to young Hugh – whose alleged fate neither he nor his audience were likely to question. John de Lexinton died in January, 1257, and his elegant learning will not be described in any history of mediaeval thought, yet his tale of young Hugh of Lincoln became a strand in English literature and a support for irrational beliefs about Jews from 1255 to Auschwitz. It is time he received his due 'credit' for such wickedness.[34]

The Hugh myth continued to resonate into the nineteenth century, when European antisemitic polemicists attempted to 'prove' the veracity of the story.[35] In the twentieth century, a well in the former Jewish neighbourhood of Jews' Court, Lincoln was advertised as 'the well in which Hugh's body was found', however this was found to have been constructed some time prior to 1928 to increase the tourist attraction of the property.[36] A Lincolnshire preparatory school, St Hugh's School, Woodhall Spa, was named after Little St Hugh in 1925; its school badge featured a ball travelling over a wall.[37]

In 1955, the Church of England placed a plaque at the site of Little Hugh's former shrine in Lincoln Cathedral, bearing these words:

By the remains of the shrine of "Little St Hugh".

Trumped up stories of "ritual murders" of Christian boys by Jewish communities were common throughout Europe during the Middle Ages and even much later. These fictions cost many innocent Jews their lives. Lincoln had its own legend and the alleged victim was buried in the Cathedral in the year 1255.

Such stories do not redound to the credit of Christendom, and so we pray:

Lord, forgive what we have been,

amend what we are,

and direct what we shall be.[38]

See also

Notes

- ^ An 1173 decretal by Pope Alexander III and a 1200 bull by Pope Innocent III confirmed that no new saints could be created except by the Pope.[1][2]

- ^ Wearing of a badge had been law for some time, but had been used as a means to gain revenue in 'fines' for non-compliance

- ^ See Paris 1852, p. 138 (links to online version)

- ^ Fuller says of Hugh: [he was] "a child, born and living in Lincoln, who by the impious Jews was stolen from his parents, and in derision of Christ and Christianity, to keep their cruel hands in use, by them crucified, being about nine years old. Thus he lost his life, but got a saintship thereby; and some afterwards persuaded themselves that they got their cures at his shrine in Lincoln.

"However, this made up the measure of the sins of the Jews in England, for which not long after they were ejected the land, or, which is the truer, unwillingly they departed themselves. And whilst they retain their old manners, may they never return, especially in this giddy and unsettled age, for fear more Christians fall sick of Judaism, than Jews recover in Christianity."[31]

References

- ^ "William Smith and Samuel Cheetham, A Dictionary of Christian Antiquities (Murray, 1875), p. 283". Boston, Little. Retrieved 4 October 2014.

- ^ "Pope Alexander III". Archived from the original on 15 October 2013. Retrieved 4 October 2014.

- ^ Hillaby & Hillaby 2013, pp. 657–58

- ^ a b Huscroft 2006, p. 102

- ^ a b c Hillaby 1994, p. 96.

- ^ Hillaby 1994, p. 96–98.

- ^ a b Editors of Encyclopaedia Britannica 2006

- ^ a b Bennett 2005

- ^ a b Langmuir 1972, pp. 459–482

- ^ Jacobs 1893, p. 96

- ^ Langmuir 1972, p. 478

- ^ Huscroft 2006, p. 102, Hillaby & Hillaby 2013, p. 658 and Langmuir 1972, pp. 477–478

- ^ Huscroft 2006, p. 102; Hillaby & Hillaby 2013, p. 658; Langmuir 1972, p. 478

- ^ Langmuir 1972, pp. 477–478

- ^ Langmuir 1972, p. 479

- ^ Langmuir 1972, p. 479; see also Hillaby & Hillaby 2013, p. 658

- ^ Langmuir 1972, pp. 480–81

- ^ Langmuir 1972, p. 481

- ^ Jacobs 1893, p. 100

- ^ Sagovsky, Nicholas. "What makes a saint? A Lincoln case study in the communion of the local and the universal Church", International Journal for the Study of the Christian Church, Volume 17, 2017 - Issue 3

- ^ "Hugh of Lincoln", The British Museum

- ^ Editors, Catholic Saints 2013, Butler 1910

- ^ David Stocker 1986

- ^ Stacey 2001

- ^ Hillaby & Hillaby 2013, p. 658.

- ^ David Stocker 1986

- ^ Hillaby 1994, p. 94-98.

- ^ Hill 1948, pp. 228–29

- ^ Simon Sharma 'The Story of the Jews Finding the Words (London: Random House 2013) p. 307-310

- ^ The Jew of Malta, Act Three, Scene Six, Line 49.

- ^ a b Fuller 1662; Lincolnshire, HUGH [SAINT HUGH OF LINCOLN, b. 1246?]

- ^ Jacobs 1904, pp. 487–488

- ^ McCabe 1980, p. 282

- ^ Langmuir 1972, pp. 481–482

- ^ Langmuir 1972, pp. 459–60

- ^ Langmuir 1972, p. 461

- ^ Martineau, Hugh (1975). Half a Century of St Hugh's School, Woodhall Spa. Horncastle: Cupit and Hindley. p. 2.

- ^ Coakley & Pailin 1993

Sources

Primary sources

- Chaucer, Geoffrey (2007). Skeat, Walter William (ed.). Chaucer's Works, Volume 4: The Canterbury Tales (ebook) (in Middle English). Project Gutenberg.

- Chaucer, Geoffrey (2000). Purves, David Laing (ed.). The Canterbury Tales, and Other Poems (ebook). Project Gutenberg.

- Fuller, Thomas (1662), The Worthies of England Vol III, London

- Paris, Matthew (1852). Giles, John Allen (ed.). Matthew Paris's English history : from the year 1235 to 1273 Vol III. London: HG Bohn.; especially Of the cruel treatment of the Jews for having crucified a boy, (page 138); How eighteen Jews were dragged to the gallows and hung, page 141; and Of the scandal originated by the Minors, page 162

- Dugdale, William (1846). Monasticon Anglicanum Volume III.; includes Annals of Burton in Latin

Secondary sources

- Hill, Francis (1948), Medieval Lincoln., Cambridge [Eng.]: University Press, LCCN 49001943, OCLC 1563484, OL 6044601M

- Hillaby, Joe (1994). "The ritual-child-murder accusation: its dissemination and Harold of Gloucester". Jewish Historical Studies. 34: 69–109. JSTOR 29779954.

- Hillaby, Joe; Hillaby, Caroline (2013). The Palgrave Dictionary of Medieval Anglo-Jewish History. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan. p. 468. ISBN 978-0230278165.

- Huscroft, Richard (2006). Expulsion: England's Jewish solution. Stroud, UK: Tempus. ISBN 978-0-752-43729-3.

- Editors of Encyclopaedia Britannica (2006). "Little Saint Hugh of Lincoln – English martyr". Encyclopædia Britannica, inc. Retrieved 4 November 2016.

Jacobs, Joseph (1904). "Hugh of Lincoln". In Singer, Isidore; et al. (eds.). The Jewish Encyclopedia. Vol. 6. New York: Funk & Wagnalls. p. 487.

Jacobs, Joseph (1904). "Hugh of Lincoln". In Singer, Isidore; et al. (eds.). The Jewish Encyclopedia. Vol. 6. New York: Funk & Wagnalls. p. 487.- Jacobs, Joseph (1893). "Little St. Hugh of Lincoln. Researches in history, archæology, and legend". Transactions (Jewish Historical Society of England). 1: 89–135. JSTOR 29777550.

- Langmuir, Gavin I (July 1972). "The Knight's Tale of Young Hugh of Lincoln". Speculum. 47 (3): 459–482. doi:10.2307/2856155. JSTOR 2856155. S2CID 162262613.

- Utz, Richard (2005). "Remembering Ritual Murder: The Anti-Semitic Blood Accusation Narrative in Medieval and Contemporary Cultural Memory". In Østrem, Eyolf (ed.). Genre and Ritual: The Cultural Heritage of Medieval Rituals. Copenhagen: Copenhagen: Museum Tusculanum Press/University of Copenhagen. pp. 145–162. ISBN 9788763502412.

- Utz, Richard (1999). "The Medieval Myth of Jewish Ritual Murder. Toward a History of Literary Reception" (PDF). The Year's Work in Medievalism. 14: 22–42.

- Bennett, Gillian (2005). Bodies: Sex, Violence, Disease, and Death in Contemporary Legend. Jackson: University of Mississippi Press. pp. 263–264. ISBN 9781578067893.

- Editors, Catholic Saints (31 July 2013). "Hugh the Little". CatholicSaints.Info.

{{cite web}}:|last1=has generic name (help) - Butler, Richard Urban (1910). "St. Hugh". Catholic Encyclopedia.

- Coakley, Sarah; Pailin, David Arthur (1993). The Making and Remaking of Christian Doctrine: Essays in Honour of Maurice Wiles. Clarendon Press. ISBN 9780198267393.

- Stacey, Robert (2001). "Anti-Semitism and the Medieval English State". In Maddicott, J. R.; Pallister, D. M. (eds.). The Medieval State: Essays Presented to James Campbell. London: The Hambledon Press. pp. 163–77.

- David Stocker (1986). "The Shrine of Little St Hugh". Medieval Art and Architecture at Lincoln Cathedral. British Archaeological Association. pp. 109–117. ISBN 978-0-907307-14-3.

History of the ballad

- Göller, Karl Heinz (1987). "Sir Hugh of Lincoln. From History to Nursery Rhyme". In Engler, Bernd; Müller, Kurt (eds.). Jewish Life and Jewish Suffering as Mirrored in English and American Literature (PDF). Schöningh: Paderborn. pp. 17–31.

- James Woodall, "'Sir Hugh': A Study in Balladry", Southern Folklore Quarterly, 19 (1955), 77— 84. https://hdl.handle.net/2027/mdp.39015038728997

- Stamper, Frances C., and Wm. Hugh Jansen. ""Water Birch": An American Variant of "Hugh of Lincoln"." The Journal of American Folklore 71, no. 279 (1958): 16–22. doi:10.2307/537953.

- McCabe, Mary Diane (1980). A critical study of some traditional religious ballads (Masters). Durham University: Durham theses. pp. 277–292. See Chapter 11, The Survival of a Saint's Legend: Sir Hugh, or The Jew's Daughter (Child 155)