Jaan Kross

This article includes a list of general references, but it lacks sufficient corresponding inline citations. (April 2022) |

Jaan Kross | |

|---|---|

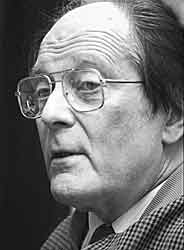

Jaan Kross in 1987, by Guenter Prust | |

| Born | 19 February 1920 Tallinn, Estonia |

| Died | 27 December 2007 (aged 87) |

| Nationality | Estonian |

| Alma mater | University of Tartu |

| Genre | novels |

| Spouse | Helga Pedusaar Helga Roos Ellen Niit |

| Children | 4, including Kristiina Ross and Eerik-Niiles Kross |

Jaan Kross (19 February 1920 – 27 December 2007)[1] was an Estonian writer. He won the 1995 International Nonino Prize in Italy.

Early life

[edit]Born in Tallinn, Estonia, son of a skilled metal worker, Jaan Kross studied at Jakob Westholm Gymnasium,[2] and attended the University of Tartu (1938–1945) and graduated from its School of Law. He taught there as a lecturer until 1946, and again as Professor of Artes Liberales in 1998.

In 1940, when Kross was 20, the Soviet Union invaded and occupied the three Baltic countries: Estonia, Latvia and Lithuania; imprisoned and executed most of their governments.[3] In 1941, Nazi Germany invaded and took over the country.

Kross was first arrested by the Germans for six months in 1944 during the German occupation of Estonia (1941–1944), suspected of what was termed "nationalism", i.e., promoting Estonian independence. Then, on 5 January 1946, when Estonia had been reconquered by the Soviet Union, he was arrested by the Soviet occupation authorities who kept him a short while in the cellar of the local NKVD headquarters, then kept him in prison in Tallinn, finally in October 1947, deporting him to a Gulag camp in Vorkuta, Russia. He spent a total of eight years in this part of North Russia, six working in the mines at the Minlag labour camp in Inta, then doing easier jobs, plus two years still living as a deportee, but not in a labour camp.[4] Upon his return to Estonia in 1954 he became a professional writer, not least because his law studies during Estonian independence were now of no value whatsoever, as Soviet law held sway.

At first, Kross wrote poetry, alluding to a number of contemporary phenomena under the guise of writing about historical figures. But he soon moved to writing prose, a genre that was to become his principal one.

Career as a writer

[edit]Recognition and translation

[edit]Kross was by far the most translated and nationally and internationally best-known Estonian writer. He received the honorary title of People's Writer of the Estonian SSR (1985) and the State Prize of the Estonian SSR (1977). He also held several honorary doctorates and international decorations, including the highest Estonian order and one of the highest German orders. In 1999 he was awarded the Baltic Assembly Prize for Literature.

In 1990 Kross won the Amnesty International Golden Flame Prize.[5] He won the 1995 International Nonino Prize in Italy. He was reportedly nominated several times for the Nobel Prize in Literature during the early 1990s.[citation needed]

Because of Kross' status and visibility as a leading Estonian author, his works have been translated into many languages, but mostly into Finnish, Swedish, Russian, German, and Latvian.[6] This is on account of geographical proximity but also a common history (for example, Estonia was a Swedish colony in the 17th century and German was the language of the upper échelons of Estonian society for hundreds of years). As can be seen from the list below by the year 2015 five books of Kross' works have been published in English translation with publishing houses in the United States and UK.[7] But a number of shorter novels, novellas, and short stories were published during Soviet rule (i.e. 1944–1991) in English translation and published in the Soviet Union.

Translations have mostly been from the Estonian original. Sometimes translations were however done, during Soviet times by first being translated into Russian and then from Russian into English, not infrequently by native speakers of Russian or Estonian. Nowadays, Kross' works are translated into English either directly from the Estonian, or via the Finnish version. A reasonably complete list of translations of works by Jaan Kross into languages other than English can be found on the ELIC website.[8]

Kross knew the German language from quite an early age as friends of the family spoke it as their mother tongue, and Kross' mother had a good command of it. His Russian, however, was mainly learnt while working as a slave labourer in the Gulag. But he also had some knowledge of Swedish and translated one crime novel by Christian Steen (pseudonym of the exile Estonian novelist Karl Ristikivi) from that Swedish. He also translated works by Pierre-Jean de Béranger, Honoré de Balzac, and Paul Éluard from French, Bertolt Brecht and Rolf Hochhuth from German, Ivan Goncharov and David Samoilov from Russian, and Alice in Wonderland, Macbeth and Othello from English.

Content and style

[edit]Kross' novels and short stories are almost universally historical; indeed, he is often credited with a significant rejuvenation of the genre of the historical novel. Most of his works take place in Estonia and deal, usually, with the relationship of Estonians and Baltic Germans and Russians. Very often, Kross' description of the historical struggle of the Estonians against the Baltic Germans is a metaphor for the contemporary struggle against the Soviet occupation. However, Kross' acclaim internationally (and nationally even after the regaining of Estonian independence) shows that his novels also deal with topics beyond such concerns; rather, they deal with questions of mixed identities, loyalty, and belonging.

Generally, The Czar's Madman has been considered Kross' best novel; it is also the most translated one. Also well-translated is Professor Martens' Departure, which because of its subject matter (academics, expertise, and national loyalty) is very popular in academia and an important "professorial novel". The later novel Excavations, set in the mid-1950s, deals with the thaw period after Stalin's death as well as with the Danish conquest of Estonia in the Middle Ages, and today considered by several critics as his finest, has not been translated into English yet; it is however available in German.[9]

Within the framework of the historical novel, Kross' novels can be divided up into two types: truly historical ones, and more contemporary narratives with an element of autobiography. In the list below, the historical ones, often set in previous centuries, include the Between Three Plagues tetralogy, set in the 16th century, A Rakvere Novel / Romance set in the 18th (the title is ambiguous), The Czar's Madman set in the 19th century, Professor Martens' Departure set at the turn of the 19th and 20th centuries, and Elusiveness / Evasion set around 1918. The semi-autobiographical novels include Kross' novel about the ultimate fates of his schoolmates, i.e. The Wikman Boys (Wikman being based on his alma mater the Westholm Grammar School – both names are of Swedish origin) a similar sort of novel about his university chums, Mesmer's Circle / Ring; the novel Excavations which describes Kross' alter ego Peeter Mirk and his adventures with archaeology, conformism, revolt, compromise and skulduggery after he has returned from the Siberian labour camps and internal exile out there. And also the novel that has appeared in English translation is titled Treading Air, and most of his short stories belong to this subgenre.

A stylistic leitmotif in Kross' novels is the use of the internal (or inner) monologue, usually when the protagonist is trying to think his way out of a thorny problem. The reader will note that every protagonist or narrator, from Timotheus von Bock in The Czar's Madman to Kross' two alter egos, Jaak Sirkel and Peeter Mirk in the semi-autobiographical novels, indulges in this. And especially Bernhard Schmidt, the luckless telescope inventor, in the novel that appeared in English as Sailing Against the Wind (2012).

Another common feature of Kross's novels is a comparison, sometimes overt but usually covert, between various historical epochs and the present day, which for much of Kross' writing life consisted of Soviet reality, including censorship, an inability to travel freely abroad, a dearth of consumer goods, the ever-watchful eye of the KGB and informers, etc. Kross was always very skilful at always remaining just within the bounds of what the Soviet authorities could accept. Kross also enjoyed playing with the identities of people who have the same, or nearly the same, name. This occurs in Professor Martens' Departure where two different Martens figures are discussed, legal experts who lived several decades apart, and in Sailing Against the Wind where in one dream sequence the protagonist Bernhard Schmidt meets a number of others named Schmidt.

When Kross was already in his late 70s he gave a series of lectures at Tartu University explaining certain aspects of his novels, not least the roman à clef dimension, given the fact that quite a few of his characters are based on real-life people, both in the truly historical novels and the semi-autobiographical ones. These lectures are collected in a book entitled Omaeluloolisus ja alltekst (Autobiographism and Subtext) which appeared in 2003.

During the last twenty years of his life, Jaan Kross occupied some of his time with writing his memoirs (entitled Kallid kaasteelised, i.e. Dear Co-Travellers – this translation of the title avoids the unfortunate connotation of the expression fellow-travellers). These two volumes ended up with a total of 1,200 pages, including quite a few photographs from his life. His life started quietly enough, but after describing quite innocuous things such as the summer house during his childhood and his schooldays, Kross moves on to the first Soviet occupation of Estonia, his successful attempt to avoid being drafted for the Waffen-SS during the Nazi German occupation, and a long section covering his experiences of prison and the labour camps. The last part describes his return from the camps and his attempts at authorship. The second volume continues from when he moved into the flat in central Tallinn where he lived for the rest of his life, plus his growing success as a writer. There is also a section covering his one-year term as a Member of Parliament after renewed independence, and his trips abroad with his wife.

Synopses

[edit]Short synopses of works available in English translation

[edit]Six books by Jaan Kross have been published in English translation, five novels and one collection of stories: The English translations appeared in the following order: The Czar's Madman 1992; Professor Martens' Departure 1994; The Conspiracy and Other Stories 1995; Treading Air 2003; Sailing Against the Wind 2012, Between Three Plagues, 2016-2018. Descriptions of the above books can also be found on various websites and online bookshops. The protagonists of several of the books listed here are based on real-life figures.

The Czar's Madman (Estonian: Keisri hull, 1978; English: 1994; translator: Anselm Hollo). This tragic novel is based on the life of a Baltic-German nobleman, Timotheus von Bock (1787–1836), who was an adjutant to the relatively liberal Czar of Russia, Alexander I. Von Bock wishes to interest the Czar in the idea of liberating the serfs, i.e. the peasant classes, people who were bought and sold almost like slaves by rich landowners. But this is too much for the Czar and in 1818 von Bock is arrested and kept, at the Czar's pleasure, in a prison in Schlüsselburg. Von Bock is released when the next Czar ascends the throne, but by that time he is having mental problems during his last years under house arrest. This is regarded as Kross's most accomplished novel, along with the Between Three Plagues tetralogy (see below).[10]

Professor Martens' Departure (Estonian: Professor Martensi ärasõit, 1984; English: 1994; translator: Anselm Hollo). In early June 1909, the ethnic Estonian professor, Friedrich Fromhold Martens (1845–1909) gets on the train in Pärnu heading for the Foreign Ministry of the Russian Empire in the capital, Saint Petersburg. During the journey, he thinks back over the events and episodes of his life. Should he have made a career working for the Russian administration as a compiler of treaties at the expense of his Estonian identity? He also muses on his namesake, a man who worked on a similar project in earlier decades. A novel that examines the compromises involved when making a career in an empire when coming from a humble background.[11]

Sailing Against the Wind (Estonian: Vastutuulelaev, 1987; English: 2012; translator: Eric Dickens). This novel is about the ethnic Estonian Bernhard Schmidt (1879–1935) from the island of Naissaar who loses his right hand in a firework accident during his teenage years. He nevertheless uses his remaining hand to work wonders when polishing high-quality lenses and mirrors for astronomical telescopes. Later on, when living in what had become Nazi Germany, he himself invents large stellar telescopes that are still to be found at, for instance, the Mount Palomar Observatory in California and on the island of Mallorca. Schmidt has to wrestle with his conscience when living in Germany as the country is re-arming and telescopes could be put to military use. But because Germany was the leading technical nation at the time, he feels reasonably comfortable there, first in the run-down small town of Mittweida, then at the main Bergedorf Observatory just outside Hamburg. But the rise of the Nazis is literally driving him mad.[12]

The Conspiracy and Other Stories (Estonian: Silmade avamise päev, 1988 – most of the stories there; English: 1995; translator: Eric Dickens). This collection contains six semi-autobiographical stories mostly dealing with Jaan Kross' life during the Nazi-German and Soviet-Russian occupations of Estonia, and his own imprisonment during those two epochs. The stories, some of which have appeared elsewhere in this translation, are. The Wound, Lead Piping, The Stahl Grammar, The Conspiracy, The Ashtray, and The Day Eyes Were Opened. In all of them, there is a tragi-comic aspect.[13]

Treading Air (Estonian: Paigallend, 1998; English: 2003; translator: Eric Dickens). The protagonist of this novel is Ullo Paerand, a restless young man of many talents. He attends a prestigious private school, but when his speculator father abandons him and his mother the money runs out. He then helps his mother run a laundry to make ends meet. He works his way up, ultimately becoming a messenger boy for the Estonian Prime Minister's office. He is even offered a chance to escape abroad by going to study at the Vatican, but stays in Estonia. This semi-autobiographical novel is set against the background of a very stormy epoch in the history of Estonia, from when the Soviets occupy the country in 1940, the German occupation the next year, the notorious bombing of central Tallinn by the Soviet airforce on 9 March 1944, and a further thirty years of life in the Estonian Soviet Socialist Republic.[14]

Between Three Plagues (Kolme katku vahel, four volumes 1970–1980; English: three volumes 2016–2018; translator: Merike Lepasaar Beecher) This is Kross' first major work and his largest in volume. The idea started out as a film script, which was shelved, then became a TV serial, and finally the four-volume suite of novels which is one of Kross' most famous works.[15] It is set in the 16th century, especially the middle, before and during the Livonian War which lasted, on and off, from the 1550s to the early 1580s. Livonia included parts of what are now Estonia and Latvia, and was by the 1550s split up into several parts ruled by Denmark, Sweden, Russia and Poland-Lithuania. The protagonist is, as is often the case with Kross, a real-life figure called Balthasar Russow (c 1536–1600), who wrote the Livonian Chronicle. The chronicle describes the political horse-trading between the various countries and churches of the day. The Estonians, mostly of peasant stock in those days, always ended up as piggies in the middle. There were also three outbreaks of the bubonic plague to contend with. Russow was the humble son of a peasant, but became a German-speaking clergyman, which was a big step up in society. The fact that he could read, let alone write a chronicle, was unusual. The tetralogy starts with a famous scene where the then-ten-year-old Balthasar watches some tightrope walkers in Tallinn, a metaphor for his own diplomatic tightrope walking later in life. He appears as something of a rough diamond throughout the books. The entire tetralogy has been translated into Dutch, Finnish, German, Latvian, Russian, and English.[16]

Short synopses of works not yet available in English

[edit]The majority of Kross's novels remain untranslated into English. These are as follows:

Under Clio's Gaze (Klio silma all; 1972) This slim volume contains four novellas. The first deals with Michael Sittow, a painter who has been working at the court of Spain but now wants to join the painters' guild in Tallinn which is as good as a closed shop (Four Monologues on the Subject of Saint George). The second story tells of an ethnic Estonian Michelson who will now be knighted by the Czar as he has been instrumental in putting down a rebellion in Russia; this is the story of his pangs of conscience, but also how he brings his peasant parents to the ceremony to show his origins (Michelson's Matriculation) The third story is set in around 1824, and about the collator of Estonian folk literature Friedrich Reinhold Kreutzwald who, after passing his exams, does not want to become a theologian but wants to study military medicine in Saint Petersburg, then the capital of the Russian Empire; meanwhile, he meets a peasant who can tell him about the Estonian epic hero Kalev, here of the epic Kalevipoeg (Two Lost Sheets of Paper). The final story is set in the 1860s, when a national consciousness was awakening in Estonia and the newspaper editor Johann Voldemar Jannsen starts an Estonian-language newspaper with his daughter Lydia Koidula and founds the Estonian Song Festival (A While in a Swivel Chair).[17]

The Third Range of Hills (Kolmandad mäed; 1974) This short novel tells the story of the ethnic Estonian painter Johann Köler (1826–1899) who had become a famous portrait painter at the Russian court in Saint Petersburg. He is now, in 1879, painting a fresco for a church in Tallinn, the capital of Estonia. As a model for his Christ, he picks out an Estonian peasant from the island of Hiiumaa. Later it transpires that the man he used as a model was a sadistic criminal, and this is held against Köler by his Baltic-German overlords.[18]

A Rakvere Novel (Rakvere romaan; 1982) The novel is set in the year 1764. The young Berend Falck is taken on by the Baroness Gertrude von Tisenhausen. Falck is an ethnic Estonian, von Tisenhausen a Baltic-German. Rakvere (Wesenberg, in German) is an Estonian provincial town and in those days the baroness dominated. Falck soon gets involved in the struggle between the townspeople and the baroness. And as he has been employed by her, he is initially obliged to take her side. But as she begins to confiscate land, he grows disillusioned with her. The townspeople, for their part, attempt to reclaim the rights that they had had earlier under Swedish colonial rule, decades before. Sweden lost Estonia to Russia around 1710, so in the epoch in which this novel is set, Rakvere and indeed Estonia are part of the Russian Empire, despite the fact that this local dispute is between the German-speaking baronial classes and Estonian-speaking peasants. A panoramic novel of divided loyalties and corruption.[19]

The Wikman Boys (Wikmani poisid; 1988) Jaan Kross' alter ego Jaak Sirkel will soon matriculate from school in the mid-1930s. Young people eagerly go to the cinema in their free time; at school, they have the usual sprinkling of eccentric teachers. Europe is gradually moving towards war, and this overshadows the lives of the young people. After the war has reached Estonia, some of Sirkel's schoolmates end up in the Soviet Army, and others fighting in the Nazi German military – the tragedy of a small country fought over by two superpowers. In the devastating Battle of Velikiye Luki, not far from the Russian-Estonian border, Estonians fight on both sides.

Excavations (Väljakaevamised; 1990) This novel first appeared in Finnish as the political situation in Estonia was very unclear owing to the imminent collapse of the Soviet Union. It tells the story of Peeter Mirk (another of Kross' alter egos) who has just returned from eight years of labour camp and internal exile in Siberia and is looking for work, in order to avoid being sent back, labelled as a "parasite to Soviet society". And he needs the money to live on. It is now 1954, Stalin is dead, and there is a slight political thaw. He finds a job on an archaeological dig near the main bastion in central Tallinn. There he finds a manuscript written in the 13th century by a leprous clergyman, a document which could overturn some of the assumptions about the history of Estonia that the Soviet occupier has. The novel also gives portraits of several luckless individuals who have been caught up in the paradoxes of German and Russian occupations.[20]

Elusiveness (Tabamatus; 1993) In 1941, a young Estonian law student is a fugitive from the occupying German Nazis, as he is suspected of being a resistance fighter. He is accused of writing certain things during the one-year Soviet occupation the previous year. But what the German occupiers dislike especially is that this young law student is writing a work about the Estonian politician and freedom fighter Jüri Vilms (1889–1918) who was obliged to flee from the Germans back in 1918 (during another period of Estonia's tangled history) and was shot by firing squad when he had just reached Helsinki, around the time that Estonia became independent of Russia.[21]

Mesmer's Circle (Mesmeri ring; 1995) Another novel involving Kross' alter ego, Jaak Sirkel, who is by now a first-year student at Tartu University. One of his fellow students Indrek Tarna has been sent to Siberia by the Reds, when the Soviets occupied Estonia in 1940. Indrek's father performs a strange ritual with several people standing around the dining table and holding hands – as Franz Mesmer did with his patients. This ritual is meant to give his boy strength by way of prayer. Others react in a more conventional way to the tensions of 1939. This is also where the reader first meets the fellow student who will become the protagonist in Kross' novel Treading Air. The novel is partly a love story, where Sirkel, a friend of Tarna's is in love with his girlfriend Riina. And Tarna is in Siberia... Conflicting loyalties. When the Germans invade Estonia Tarna can return to Estonia. The Riina problem gets more tangled.[22]

Tahtamaa (idem; 2001) Tahtamaa is a plot of land by the sea. This novel is described by Rutt Hinrikus of the Estonian Literary Museum in a short review article on the internet.[23] It is a novel about the differences in mentality between the Estonians who lived in the Soviet Union, and those that escaped abroad, and their descendants. It is also a novel about greed and covetousness, ownership, and is even a love story between older people. This is Kross' last novel and is set in the 1990s, after Estonia regained its independence.

Death

[edit]Jaan Kross died in Tallinn, at the age of 87, on 27 December 2007. He is survived by his wife, children's author and poet Ellen Niit, and four children. The President of Estonia (at the time), Toomas Hendrik Ilves, praised Kross "as a preserver of the Estonian language and culture."[5]

Kross is buried at the Rahumäe cemetery in Tallinn.[24]

Quotes

[edit]- "He was one of those who kept fresh the spirits of the people and made us ready to take the opportunity of restoring Estonia's independence." — Toomas Hendrik Ilves[5]

Tribute

[edit]On 19 February 2020, Google celebrated his 100th birthday with a Google Doodle.[25]

Bibliography

[edit]Selected Estonian titles in chronological order

- Kolme katku vahel (Between Three Plagues), 1970–1976. A tetralogy of novels.

- Klio silma all (Under Clio's Gaze), 1972. Four novellas.

- Kolmandad mäed (The Third Range of Hills), 1974. Novel.

- Keisri hull 1978 (English: The Czar's Madman, Harvill, 1992, in Anselm Hollo's translation). Novel.

- Rakvere romaan (A Rakvere Novel), 1982. Novel.

- Professor Martensi ärasõit 1984, (English: Professor Martens' Departure, Harvill, 1994, in Anselm Hollo's translation). Novel.

- Vastutuulelaev 1987 (English: Sailing Against the Wind, Northwestern University Press, 2012, in Eric Dickens' translation). Novel.

- Wikmani poisid (The Wikman Boys), 1988. Novel.

- Silmade avamise päev 1988, (English: The Conspiracy and Other Stories, Harvill, 1995, in Eric Dickens' translation). Short-stories.

- Väljakaevamised (Excavations), 1990. Novel.

- Tabamatus (Elusiveness), 1993. Novel.

- Mesmeri ring (Mesmer's Circle), 1995. Novel.

- Paigallend 1998 (English: Treading Air, Harvill, 2003, in Eric Dickens' translation). Novel.

- Tahtamaa, (Tahtamaa) 2001. Novel.

- Kallid kaasteelised (Dear Co-Travellers) 2003. First volume of autobiography.

- Omaeluloolisus ja alltekst (Autobiographism and Subtext) 2003. Lectures on his own novels.

- Kallid kaasteelised (Dear Co-Travellers) 2008. Second (posthumous) volume of autobiography.

Stories in English-language anthologies:

- Four Monologues on the Subject of Saint George in the anthology of Estonian literature The Love That Was Progress Publishers, Moscow, 1982, translator Robert Dalglish.

- Kajar Pruul, Darlene Reddaway: Estonian Short Stories, Northwestern University Press, Evanston, Illinois, 1996 (The stories: Hallelujah and The Day His Eyes Are Opened. Translator: Ritva Poom.)

- Jan Kaus (editor): The Dedalus Book of Estonian Literature, Dedalus Books, Sawtry, England, 2011 (The story: Uncle. Translator: Eric Dickens.)[26]

Kross the essayist

Between 1968 and 1995, Kross published six small volumes of essays and speeches, a total of about 1,200 small-format pages.[27]

Biography

The only biography of any length of Jaan Kross to date was first published in Finnish by WSOY, Helsinki, in 2008 and was written by the Finnish literary scholar Juhani Salokannel, the then director of the Finnish Institute in Tallinn. Salokannel is also the Finnish translator of several of Kross's key works[28] His Kross biography is entitled simply Jaan Kross and has not yet appeared in any other language except Finnish and Estonian. It covers both the biographical and textual aspects of Kross' work, also dealing with matters such as Kross the poet and Kross the playwright.[29]

References

[edit]- ^ International Herald Tribune: Jaan Kross, Estonia's best known writer, dies at 87

- ^ Estonian Literature Information Centre article on Jaan Kross

- ^ Tannberg and others, pages 238–267

- ^ ELIC article on Jaan Kross and The Conspiracy and Other Stories, pages vii and viii, and pages 118–453 of the first volume of his memoirs (op. cit.)

- ^ a b c "Breaking News, World News & Multimedia". Retrieved 23 March 2018.

- ^ See Bibliografia op.cit.pages 100–139

- ^ See list of publications. The publishing houses are, Harvill (now Harvill Secker), London, and Northwestern University Press, Illinois

- ^ "ELIC website". Archived from the original on 3 March 2016. Retrieved 23 March 2018.

- ^ Ausgrabungen, Dipa Verlag, 2002, translator: Cornelius Hasselblatt

- ^ This novel has also been translated into Bulgarian, Czech, Danish, Dutch, Finnish, French, German, Hungarian, Italian, Japanese, Latvian, Lithuanian, Norwegian, Polish, Portuguese, Russian, Slovak, Spanish, Swedish, and Ukrainian

- ^ This novel has also been translated into Dutch, Finnish, French, German, Hungarian, Latvian, Norwegian, Russian, Spanish, and Swedish

- ^ This novel is also available in French, in Jean-Luc Moreau's translation, 1994

- ^ The story The Days Eyes Were Opened is also available in the anthology Estonian Short Stories, edited by Kajar Pruul and Darlene Reddaway (op.cit.), there entitled The Day His Eyes Are Opened

- ^ This novel has also been translated into Dutch, Finnish. Latvian, Russian, and Swedish

- ^ Salokannel, op. cit. pages 175–228

- ^ Some of the above information is from the Finnish translation by Kaisu Lahikainen and Jouko Vanhanen, WSOY, Helsinki, 2003, 1240 pages, where the four volumes were published together.

- ^ These four novellas have been translated into Finnish and Russian as one book.

- ^ Available in Finnish translation

- ^ Book description based on the blurb of the Swedish translation by Ivo Iliste, Romanen om Rakvere, Natur & Kultur. Stockholm, 1992. It has also been translated into Finnish and German

- ^ Book description based on the blurb of the Swedish translation by Ivo Iliste, Fripress / Legenda, Stockholm, 1991

- ^ Book description based on the blurb of the Swedish translation by Ivo Iliste, Natur & Kultur, Stockholm, 1993. This novel is also available in Finnish and French.

- ^ Book description based on the blurb of the Dutch translation by Frans van Nes, De ring van Mesmer, Prometheus, Amsterdam, 2000

- ^ "Jaan Kross. Tahtamaa. – Free Online Library". www.thefreelibrary.com. Retrieved 23 March 2018.

- ^ "Cemetery Portal".

- ^ "Jaan Kross' 100th Birthday". Google. 19 February 2020.

- ^ "Estonian Literature". www.estlit.ee. Retrieved 23 March 2018.

- ^ These volumes are entitled Vahelugemised I-VI i.e. Intertexts I-VI

- ^ Keisri hull (Finnish: Keisarin hullu; 1982), Rakvere romaan (Finnish: Pietarin tiellä; 1984) and Professor Martensi ärasõit (Finnish, 1986)

- ^ Estonian version: Juhani Salokannel: Jaan Kross, Eesti Keele Sihtasutus, 2009, 542 pages, ISBN 978-9985-79-266-7, translated into Estonian by Piret Saluri

Sources

[edit]- Juhani Salokannel: Jaan Kross, Eesti Keele Sihtasutus, Tallinn, 2009, 530 pages. (Estonian translation of a Finnish work; the largest biography of Kross available in any language.)

- Loccumer Protokolle '89 – Der Verrückte des Zaren 1989, 222 pages. (Festschrift in German.)

- All works of Kross in their original Estonian versions. (Also some in Finnish and Swedish translation.)

- Jaan Kross: De ring van Mesmer, Prometheus, Amsterdam, 2000 (Dutch translation by Frans van Nes of Mesmeri ring / Mesmer's Circle).

- Cornelius Hasselblatt: Geschichte der estnischen Literatur, Walter de Gruyter (publishers), 2006, pages 681–696 (in German).

- Both volumes of Jaan Kross' autobiography entitled Kallid kaasteelised I-II, Eesti Keele Sihtasutus, Tallinn, 2003 and 2008. A total of some 1,200 pages.

- Eesti kirjanike leksikon (Estonian bio-bibliographical writers' reference work), 2000. The article on Jaan Kross there.

- Various reviews and obituary notices in The Guardian, TLS, etc., by Doris Lessing, Tibor Fischer, Paul Binding, Ian Thomson, and others.

- Translator Eric Dickens' introductions to The Conspiracy and Other Stories, Treading Air. and Sailing Against the Wind.

- Material on the Estonian Literature Information Centre website pertaining to Jaan Kross.

- Petri Liukkonen. "Jaan Kross". Books and Writers.

- A couple of articles on Kross in the Estonian Literary Magazine (ELM), published in Tallinn, especially during Kross' 80th birthday year of 2000.

- Tannberg / Mäesalu / Lukas / Laur / Pajur: History of Estonia, Avita, Tallinn, 2000, 332 pages.

- Andres Adamson, Sulev Valdmaa: Eesti ajalugu (Estonian History), Koolibri, Tallinn, 1999, 230 pages.

- Arvo Mägi: Eesti rahva ajaraamat (The Estonian People's History Book), Koolibri, Tallinn, 1993, 176 pages.

- Silvia Õispuu (editor): Eesti ajalugu ärkimisajast tänapäevani (Estonian History From National Awakening to the Present Day), Koolibri, 1992, 376 pages.

- Mart Laar: 14. juuni 1941 (14 June 1941; about the deportations to Siberia), Valgus, Tallinn, 1990, 210 pages.

- Mart Laar and Jaan Tross: Punane Terror (Red Terror), Välis-Eesti & EMP, Stockholm, Sweden, 1996, 250 pages.

- Andres Tarand: Cassiopeia (the author's father's letter from the labour camps), Tallinn, 1992, 260 pages.

- Imbi Paju: Förträngda minnen (Suppressed Memories), Atlantis, Stockholm, 2007, 344 pages (Swedish translation of the Estonian original: Tõrjutud mälestused.)

- Venestamine Eestis 1880–1917 (Russification in Estonia 1880–1917; documents), Tallinn, 1997, 234 pages.

- Molotovi-Ribbentropi paktist baaside lepinguni (From the Molotov–Ribbentrop Pact to the Bases Agreement; documents), Perioodika, Tallinn, 1989, 190 pages.

- Vaime Kabur and Gerli Palk: Jaan Kross – Bibliograafia (Jaan Kross- Bibliography), Bibilotheca Baltica, Tallinn, 1997, 368 pages.

External links

[edit]- Guardian biography 2003: https://www.theguardian.com/books/2003/jul/05/featuresreviews.guardianreview4

- Estonian Literature Information Centre profile: https://web.archive.org/web/20140222095137/http://www.estlit.ee/?id=10878&author=10878&c_tpl=1066&tpl=1063

- 1920 births

- 2007 deaths

- Writers from Tallinn

- Members of the Riigikogu, 1992–1995

- Estonian male novelists

- Estonian male short story writers

- 20th-century Estonian novelists

- 21st-century Estonian novelists

- 20th-century Estonian poets

- Estonian male poets

- 20th-century short story writers

- 21st-century short story writers

- 20th-century male writers

- 21st-century male writers

- Gulag detainees

- People's Writers of the Estonian SSR

- Honoured Writers of the Estonian SSR

- Herder Prize recipients

- Recipients of the Order of the Badge of Honour

- Recipients of the Order of the National Coat of Arms, 1st Class

- Burials at Rahumäe Cemetery