Judiciary Square

Judiciary Square | |

|---|---|

Aerial view of Judiciary Square in April 2007 | |

| |

| Coordinates: 38°53′43″N 77°1′6.5″W / 38.89528°N 77.018472°W | |

| Country | United States |

| District | Washington, D.C. |

| Ward | Ward 6 |

| Government | |

| • Councilmember | Charles Allen |

Judiciary Square is a neighborhood in the northwest quadrant of Washington, D.C., the vast majority of which is occupied by various federal and municipal courthouses and office buildings. Judiciary Square is located roughly between Pennsylvania Avenue to the south, H Street to the north, 6th Street to the west, and 3rd Street to the east. The center of the neighborhood is an actual plaza named Judiciary Square. The Square itself is bounded by 4th Street to the east, 5th Street to the west, D Street and Indiana Avenue to the south, and F Street to the north. The neighborhood is served by the Judiciary Square station on the Red Line of the Washington Metro, in addition to Washington Metropolitan Area Transit Authority bus stops.

The Square was included in the 1791 L'Enfant Plan, which planned the layout of the nation's new capital. The plans were slightly altered during the following years. Development in the neighborhood was slow during the first half of the 19th-century. There were only a few shanties and a small hospital utilized by recent immigrants. When construction of the District of Columbia City Hall began in 1820, it led to an increase in development around the Square. Houses and places of worship were built, including the First Unitarian Church (now the All Souls Church, Unitarian). Other denominations soon followed with building impressive structures, such as Trinity Episcopal Church.

The area became a fashionable place to live, despite many lots on the northern side being undeveloped, and Goose Creek passing through the neighborhood. Prominent residents during the 19th-century include Vice President John C. Calhoun, statesman Daniel Webster, Chief Justice of the U.S. Supreme Court Roger B. Taney, and architect Charles Bulfinch. During the Civil War, the buildings and open lots around the Square were commandeered to treat wounded Union soldiers. At the beginning of the war, the Square's hospital was destroyed in a fire, so another hospital opened on the Square. There was also a large brick jail on the Square, that probably hindered development in the vicinity. After President Abraham Lincoln was assassinated, local citizens raised money to install a statue of Lincoln that became the nation's first memorial to the slain president.

Alexander "Boss" Shepherd improved many areas of the neighborhood by having the streets graded and paved, sewer lines installed, and adding landscaping, which created a park-like setting in the Square. A massive new building on the north side of the Square, the Pension Building, was completed in 1887. By that time the residents in the neighborhood were mostly lawyers, doctors, professors, and other white-collar professions, due to the proximity of the city hall, hospital, and Columbian College, now known as George Washington University. The installation of streetcars resulted in further development. It was around this time, several older buildings on 4 1/2 Street were demolished and replaced with John Marshall Park. During the 20th-century, the area became less residential, especially after the construction of multiple judicial buildings. Most prominent citizens had already left the area to live in more fashionable neighborhoods. The area became mostly a neighborhood where office and judicial employees worked. With the construction of the Judiciary Square station, there was a sharp increase in commercial development. The largest project, Capitol Crossing, began in the 21st-century.

There are many public artworks in the neighborhood, in addition to the Lincoln statue. The list includes the Darlington Memorial Fountain, George Gordon Meade Memorial, and Chief Justice John Marshall. Most of the neighborhood is listed as contributing properties to the Pennsylvania Avenue National Historic Site, and the Square itself is included in the historic landmark designation for the L'Enfant Plan. Additional historic buildings besides City Hall and the Pension Building include the Adas Israel Synagogue, the E. Barrett Prettyman United States Courthouse, Germuiller Row, and the Henry Daly Building.

Location

[edit]The Judiciary Square plaza, which encompasses 18 acres (7.3 ha), is on Squares 487E, 488E, and 489E, and is bounded by 4th Street to the east, 5th Street to the west, D Street and Indiana Avenue to the south, and F Street to the north.[1][2] The Judiciary Square neighborhood, which encompasses Squares 486, 488, 489, 490, 518, 529, 531, and 533, is roughly bounded by C Street, Constitution Avenue, and Pennsylvania Avenue to the south, 3rd and 4th Street to the east, G Street to the north, and 6th Street to the west. Along the north side of the Square is the Judiciary Square station of the Washington Metro.[1]

Many of the structures in the Square are judicial buildings, owned by either the federal or local government, as was originally planned in the early history of the neighborhood. The neighborhood includes additional judicial and municipal buildings, commercial buildings, residential properties, and a church. South of the Square is John Marshall Park, which provides nearby workers a place to gather. Two buildings to the west of the park are the Embassy of Canada and the former Newseum, both of which are modern structures.[1]

Additional modern structures in the neighborhood include the Judiciary Square station entrance, the National Law Enforcement Officers Memorial and associated National Law Enforcement Museum, the H. Carl Moultrie Courthouse, Engine Company No. 2, John Marshall Park and its statues, and the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine, although it incorporates the façades of several historic buildings.[1]

History

[edit]18th century

[edit]

When the decision was made to create a new capital city after the Revolutionary War, President George Washington selected engineer and architect Pierre Charles L’Enfant to design it. The L'Enfant Plan was presented in 1791, which included numerous large squares, connected by avenues. In L'Enfant's plan, the area that become Judiciary Square was Reservation 7 on land owned by David Burnes, and one of the largest out of the original 17 parcels included in his plan. It was designed to be three square blocks, in an area that would be home to the United States Supreme Court Building and other judicial buildings. The plan was to create a design that would form a triangle between the United States Capitol, the White House, and the Supreme Court Building.[1][2]

After L'Enfant was fired and replaced with Andrew Ellicott, there were several changes made to the Square's plans, including size of the Square, removing building sites, and adding cross-through streets. The neighborhood around the planned Square was on sloping land that gradually reached street level at Pennsylvania Avenue. Goose Creek ran diagonally through the Square in addition to another tributary of the creek entering from the north.[1]

Another plan for the city was completed in 1797 by James R. Dermott. Washington and President John Adams both selected this plan, which was more cohesive and did not include planned buildings, to be the final draft. The map includes the name, Judiciary Square, which does not appear on the L'Enfant Plan or Ellicott Plan.[1]

19th century

[edit]Development was slow around the Square. By 1802, there were six shanties occupied by Irish immigrants on the southern edge of the Square. There was also a small hospital around the Square to treat immigrants workers. That building was later converted into a poorhouse. The last building around the square at that time was a barn, which housed prisoners waiting to be transferred to other facilities. In 1802, the U.S. Congress ordered local government official Daniel Brent to construct a jail, later nicknamed the McGurck Jail after a murderer was confined there until his execution, in the center of the Square.[1][2][3] George Hadfield designed the $8,000 two-story building.[2]

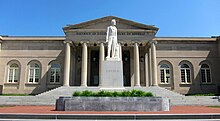

Robert King produced a fourth version of a city map which showed Judiciary Square as rectangular. The first major building erected in the area was the District of Columbia City Hall, designed by Hadfield, which was constructed from 1820 to the 1840s. Despite the building not being completed, the city government and circuit court for Washington County, D.C., moved into it beginning in 1822.[1][2] After city hall came into use, there was development in the neighborhood. Architect James Hoban lived in a house on the corner of 5th and D Streets. The city's registrar, William Hewitt, built a large home near 6th and D Streets, a few doors down from architect Charles Bulfinch.[1]

The First Unitarian Church, designed by Bulfinch and now known as All Souls Church, Unitarian, was built in 1822 at the corner of 6th and D Streets. Other buildings constructed in the 1820s include a Masonic Temple and First Presbyterian Church, located on 4 1/2th Street, the Wesley Methodist Church, Trinity Episcopal Church, designed by James Renwick Jr., the American Theater, and public baths. The area's houses of worship were numerous. In addition to the aforementioned churches, German immigrants built St. Mary Mother of God Church and a synagogue for the Washington Hebrew Congregation. Years later, the Adas Israel Synagogue was built at 6th and G Streets by Eastern European and Russian Jews.[1]

A new jail designed by Robert Mills was built on the northeast corner of the Square in 1839, replacing the one built in 1802. The former jail was renovated into the Washington Infirmary Hospital, operated by Columbian College, now known as George Washington University. A few years later public school Fifth Street Schoolhouse was built near the hospital..[1][2] In 1840, the Rittenhouse Academy opened at 3rd Street and Indiana Avenue, which was a sign that area residents could afford tuition.[1]

In the following decades, Judiciary Square had a heavily residential population. By the 1850s-1860s, its proximity to the courthouses attracted lawyers, judges, and clerks to the neighborhood, while its location between the White House and the Capitol made it ideal for government employees. Among its most prominent residents around this time were Chief Justice Roger B. Taney, Senator Thomas Hart Benton, Vice President John C. Calhoun, statesman Daniel Webster, and Mayor Richard Wallach.[1][2] There were still many empty lots on the north and east sides of the Square during this period, possibly due to the sloping terrain or proximity to the jail.[2]

During the Civil War, the buildings surrounding the Square were commandeered by the federal government and used as medical facilities for wounded Union soldiers. The Washington Infirmary Hospital was also converted into a military hospital. Tragedy struck on November 3, 1861, when a fire broke out inside the hospital, resulting in several deaths. A new hospital, U.S. General Hospital, was constructed in the Square, as was the nearby Providence Hospital, which survived for almost 100 years.[1][2][3] One building constructed during the war and faced the Square contained a small library, founded by Elida B. Rumsey, and her fiancé, John A Fowle. Congress allocated money for them to construct a one-story building on the Square to use as a library, which was completed on their wedding day in 1863.[2]

As the war continued in 1865, President Abraham Lincoln was assassinated, shocking the city's residents. An association was soon formed to raise money for a monument to the slain president. On the three year anniversary of Lincoln's death, the statue of Abraham Lincoln by sculptor Lot Flannery was installed in front of City Hall, becoming the first monument in the nation honoring Lincoln.[1][4]

In the years following the war, there was a large influx of people moving into the city, but many areas had not yet been graded or plotted. Alexander "Boss" Shepherd was responsible for large-scale improvements to the city. This included modernizing the Judiciary Square neighborhood with public work projects, including paved roads, adding sewer lines, and landscaping public land. Additional improvements included building a small public restroom, adding footpaths, narrowing the roads on the southern end of the Square, and adding a fountain in the Square. The school and old jail were demolished by 1878 and replaced with green space and the Goose Creek was drained. The goal was to make the Square a landscaped area similar to ones designed by Andrew Jackson Downing.[1][2]

Expansion of City Hall based on the design of Edward Clark began in 1882, the same year the cornerstone was laid for the massive Pension Building (now known as the National Building Museum), designed by Montgomery C. Meigs and located on the northern end of the Square. The building was inspired by the Palazzo Farnese, Palazzo della Cancelleria, and the Santa Maria degli Angeli e dei Martiri.[1] The building encompassed 112,500 square feet (10,450 m2) of the Square, and with the largest atrium in Washington, D.C., became the place where many United States presidential inauguration balls took place.[2][4]

By the end of the 1880s, most lots around the Square were developed, with houses and offices for lawyers, doctors, and professors. Some of the earlier buildings on 4 1/2 Street were demolished to make way for John Marshall Park, which includes the sculpture Chief Justice John Marshall. The population of the city nearly quadrupled between 1860 and 1900, and many of the new residents lived in older houses and alley dwellings. The neighborhood, which had been a fashionable area for a few decades, saw wealthier residents move to other areas of the city as more working-class people moved into Judiciary Square. A streetcar line on F Street led to rapid commercial development on the neighborhood's west side. The first apartment building constructed in the neighborhood was the Harrison Apartment Building, at the corner of 3rd and G Streets. This led to additional apartment buildings being constructed in the area. By the end of 19th century, many office buildings were constructed in the neighborhood, signaling a transformation of the surrounding area from residential to commercial.[1]

20th century

[edit]The city saw additional growth in the population and more apartment buildings were constructed in the Judiciary Square neighborhood. Most of the remaining houses built in the 19th-century were converted into boarding houses. After the city's John A. Wilson Building was constructed in 1908, the old City Hall housed the United States District Court for the District of Columbia, and the District of Columbia Court of Appeals moved into a new building on the Square.[1][2]

The old City Hall was refurbished in the 1910s and the grounds further landscaped. The statue of Lincoln was removed during renovations, but was returned after complaints from citizens. In 1923, the Washington Bar Association installed the Darlington Memorial Fountain in honor of one its members. The bronze fountain with statues, designed by C. Paul Jennewein, was placed on the southwest corner of the Square. The following year the General Jose de San Martin Memorial, by sculptor Augustin-Alexandre Dumont, was installed in the center of the Square, where it remained for several decades.[1][2] The Albert Pike Memorial, designed by sculptor Gaetano Trentanove, was installed across the street from the Square in 1901.[1]

In the early decades of the 20th-century, the German immigrant population was replaced with Greek, Irish, and Italian immigrants, and the eastern side of Judiciary Square became an enclave of Italians, the equivalent of a Little Italy, though it was never called that. The Italian neighborhood rested on the eastern edge of the square proper, stretching eastward to about 2nd Street. The heart of the community was Holy Rosary Church, a chapel built at 3rd and F Streets.[5]

By the 1920s, buildings along G Street were mostly restaurants and shops that catered to office workers.[1] During the Great Depression, there were often homeless people sleeping in the Square each night. Police officers would wake them up before government and commercial employees arrived for work. The rise of automobile ownership wreaked havoc to the Square. Some of the outer edges were turned into parking spaces, and when those were full, some commuters would park on the Square's sidewalks and green space.[2]

As part of the Public Works Administration during the Great Depression, additional court buildings were constructed on the Square: the District of Columbia Recorder of Deeds Building, the Municipal Court Building, and the D.C. Juvenile Court Building. All four buildings are cohesive in design. Additional local and federal buildings constructed around this time include the Henry Daly Building, the E. Barrett Prettyman United States Courthouse, and the large US General Accounting Office Building.[1][2]

In the 1960s, due to growing traffic issues, there were plans for a Metro transit system to be built in Washington, D.C. Construction of the Washington Metropolitan Area Transit Authority (WMATA) headquarters on the corner of 5th and F Streets was completed in 1974. Groundbreaking for the Judiciary Square station, designed by Harry Weese, took place in 1969. During construction, the General Jose de San Martin Memorial was moved and now stands along Virginia Avenue. The station opened in 1976.[1][2]

There was a boon in development around the neighborhood after the Metro station was announced. The United States Tax Court Building at 3rd and D Streets was completed in 1974, and the following year, the H. Carl Moultrie Courthouse opened across from the Square's southern end. The Judiciary Plaza Office Building, designed by Vlastimil Koubek and across the street from the Square, was completed in 1981. The Canadian embassy, on the southern border of the neighborhood, was built in 1989.[1][2]

There were plans to demolish the Pension Building, but due to historic preservationists, it was converted into the National Building Museum in the 1980s. In 1989, the Square was chosen to be the site where a memorial to police officers who died in the line of duty would be built. The National Law Enforcement Officers Memorial was completed in 1991 and includes four bronze lion sculptures.[1][2][4] During the 1990s, additional office buildings were constructed in the neighborhood, including the FBI District of Columbia Field Office, Koubek's One Judiciary Square, and the Judiciary Center. The building boom extended into the next decade.[1][4]

21st century

[edit]Construction projects in the 2000s included an $85 million renovation of the old City Hall, which included adding a modern atrium to the rear of the building and installing an underground courtroom. Outside this rear entrance is the National Law Enforcement Museum. Another museum that opened nearby was in the Keck Center, home of the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine, until it closed in 2017.[1] The Newseum opened on Pennsylvania Avenue in 2009, but closed ten years later. It now houses the Paul H. Nitze School of Advanced International Studies.[6]

The District government finalized a deal in 2010 with the Louis Dreyfus Group to construct Capitol Crossing, a 2,100,000-square-foot (200,000 m2) mixed-use development in the airspace over the Center Leg Freeway (Interstate 395). The $1.3 billion office, residential, and retail project at the east end of the Judiciary Square neighborhood will also restore the area's original L'Enfant Plan street grid by reconnecting F and G Streets over the freeway. The project awaited final regulatory approval for several years and construction began in 2016.[7] Part of the construction process necessitated moving the Adas Israel Synagogue, which had been moved twice decades earlier for construction projects. The original building and a modern addition are now the Lillian & Albert Small Capital Jewish Museum, which opened in 2023.[8]

Historic properties

[edit]

Judiciary Square itself is listed on the National Register of Historic Places (NRHP) and District of Columbia Inventory of Historic Sites (DCIHS), as a part of the L'Enfant Plan, which was added to the DCIHS on March 7, 1968, and the NRHP on April 24, 1997. A large portion of the neighborhood also contains contributing properties to the Pennsylvania Avenue National Historic Site, listed on the NRHP on October 15, 1966, and the DCIHS on June 19, 1973.[9]

Additional structures listed on both the NRHP and DCIHS include: the Adas Israel Synagogue, the District of Columbia City Hall, which is also a National Historic Landmark (NHL), the E. Barrett Prettyman United States Courthouse, Germuiller Row, the Harrison Apartment Building, the Henry Daly Building, the Moran Building, the National Building Museum (NHL), the US General Accounting Office Building, the United States Court of Military Appeals Building, and the United States Tax Court Building. The Albert Pike Memorial and George Gordon Meade Memorial are collectively listed with 16 other monuments on the NRHP and DCIHS as Civil War Monuments in Washington, D.C.[9]

Public art

[edit]There are many public artwork and monuments in the Judiciary Square neighborhood. The oldest one is Abraham Lincoln (1868), located in front of the old City Hall. The second oldest is Chief Justice John Marshall (1883) by William Wetmore Story, sited in John Marshall Park. The Albert Pike Memorial, which no longer features the statue of Albert Pike, was torn down by protesters after the murder of George Floyd due to Pike being a former general in the Confederate Army. The 1923 Darlington Memorial Fountain, which includes two bronze statutes on top of the fountain, was installed in 1923.[1]

The next oldest public artwork in the neighborhood is the large George Gordon Meade Memorial, designed by Charles Grafly and erected in 1927, which stands in front of the E. Barrett Prettyman United States Courthouse. The statue of William Blackstone, designed by Paul Wayland Bartlett and installed in 1943, is also located in front of the Prettyman Courthouse.[1] Trylon of Freedom by C. Paul Jennewein is the third sculpture in front of the Prettyman Courthouse and was installed in 1954.[10]

The abstract sculpture, She Who Must Be Obeyed, is in between the Henry Daly Building and Frances Perkins Building. It was created by Tony Smith and installed in 1975. The Chess Players is on the east side of John Marshall Park and was installed in 1983.[1] The National Law Enforcement Officers Memorial and its bronze lions were completed in 1991. Ashes to Answers is a 2013 statue in front of the Fire Station 2.[11]

Transportation

[edit]The neighborhood is served by two forms of public transit. Entrances to the Judiciary Square station on the Washington Metro's Red Line are on the northern and eastern ends of the Square.[12] The second form is Metrobus with several bus stops in the neighborhood and nearby vicinity, including ones on 6th Street, E Street, H Street, and Pennsylvania Avenue.[13] Other forms of transportation in the neighborhood include Capital Bikeshare stations at 4th and D Streets, and 5th and F Streets.[14] A few blocks east of Judiciary Square is Washington Union Station, where commuters on the MARC Train and Amtrak arrive.[15]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x y z aa ab ac ad ae af Trieschmann, Laura; Schoenfeld, Andrea; Singh, Paul (October 25, 2018). "Judiciary Square Historic District - Application for Historic Landmark or Historic District Designation" (PDF). District of Columbia Office of Planning - Historic Preservation Office. Archived (PDF) from the original on February 7, 2024. Retrieved February 11, 2024.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s "Historic American Buildings Survey - Judiciary Square" (PDF). National Park Service. Archived (PDF) from the original on February 7, 2021. Retrieved February 11, 2024.

- ^ a b Croggon, James (May 3, 1913). "Old Washington: Judiciary Square – Part 1". The Evening Star. p. 10. Archived from the original on February 12, 2024. Retrieved February 11, 2024.

- ^ a b c d Bednar, Michael (2006). L'enfant's Legacy: Public Open Spaces in Washington, D.C. Johns Hopkins University Press. pp. 121–129. ISBN 9780801883187.

- ^ Kiger, Patrick (February 12, 2015). "The Closest Thing to a 'Little Italy' in Washington". WETA. Archived from the original on March 24, 2023. Retrieved February 11, 2024.

- ^ Clabaugh, Jeff (September 9, 2022). "Former Newseum almost ready for Johns Hopkins graduate students". WTOP. Archived from the original on January 21, 2024. Retrieved February 11, 2024.

- ^ Meyer, Eugene L. (October 25, 2016). "A Project Mends a Gash in the Street Grid of Washington". The New York Times. Archived from the original on April 22, 2023. Retrieved February 11, 2024.

- ^ Cirruzzo, Chelsea (June 9, 2023). "Capital Jewish Museum opens in D.C." Axios. Archived from the original on January 22, 2024. Retrieved February 11, 2024.

- ^ a b "District of Columbia Inventory of Historic Sites" (PDF). District of Columbia Office of Planning - Historic Preservation Office. September 30, 2009. Archived (PDF) from the original on October 1, 2020. Retrieved February 11, 2024.

- ^ "Where's the Art?". U.S. General Services Administration. Archived from the original on December 4, 2023. Retrieved February 11, 2024.

- ^ Kelly, John (October 29, 2013). "Washington's newest memorial honors dogs who sniff out suspicious fires". The Washington Post. Archived from the original on October 4, 2015. Retrieved February 11, 2024.

- ^ "Metro Bus Stops" (PDF). WMATA. 2022. Archived (PDF) from the original on January 21, 2024. Retrieved February 12, 2024.

- ^ "Metro Bus Stops". WMATA. Archived from the original on February 12, 2024. Retrieved February 12, 2024.

- ^ "Capital Bikeshare Locations". Government of the District of Columbia. Archived from the original on February 12, 2024. Retrieved February 12, 2024.

- ^ Abedje, Tadiwos (December 21, 2023). "Metro riders should prepare for repairs to part of Red Line in downtown DC". WTOP. Archived from the original on December 31, 2023. Retrieved February 12, 2024.

External links

[edit] Media related to Judiciary Square at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Judiciary Square at Wikimedia Commons