Mongkut

| |

|---|---|

| King Rama IV | |

Portrait by John Thomson, c. 1865 | |

| King of Siam | |

| Reign | 2 April 1851 – 1 October 1868 |

| Coronation | 15 May 1851 |

| Predecessor | Nangklao (Rama III) |

| Successor | Chulalongkorn (Rama V) |

| Viceroy | Pinklao (1851–1866) |

| Born | 18 October 1804 Bangkok, Siam |

| Died | 1 October 1868 (aged 63) Bangkok, Siam |

| Spouse |

|

| Issue more... |

|

| House | Chakri dynasty |

| Father | Phutthaloetlanaphalai (Rama II) |

| Mother | Sri Suriyendra |

| Religion | Theravada Buddhism |

| Signature | |

Mongkut (Thai: มงกุฏ; 18 October 1804 – 1 October 1868) was the fourth king of Siam from the Chakri dynasty, titled Rama IV.[1] He ruled from 1851 to 1868. His full title in Thai was Phra Poramenthra Ramathibodhi Srisindra Maha Mongkut Phra Chomklao Chao Yu Hua Phra Sayam Thewa Maha Makut Witthaya Maharat (พระบาทสมเด็จพระปรเมนทรรามาธิบดีศรีสินทรมหามงกุฎ พระจอมเกล้าเจ้าอยู่หัว พระสยามเทวมหามกุฏวิทยมหาราช).[2]

The reign of Mongkut was marked by significant modernization initiatives and diplomatic engagements, which played pivotal roles in shaping Thailand's trajectory towards progress and international relations. Siam first felt the pressure of Western expansionism during Mongkut's reign. Mongkut embraced Western innovations and initiated the modernization of his country, both in technology and culture—earning him the nickname "The Father of Science and Technology" in Siam.

Mongkut was also known for appointing his younger brother, Prince Chutamani, as Second King, crowned in 1851 as King Pinklao. Mongkut told the country that Pinklao should be respected with equal honor to himself (as King Naresuan had done with his brother Ekathotsarot in 1583). During Mongkut's reign, the power of the House of Bunnag reached its zenith: It became the most powerful noble family of Siam.

Mongkut is known in the West primarily through the lens of the 1951 musical The King and I and its 1956 film adaptation.

Early life

[edit]

Mongkut (มงกุฎ, literal meaning: crown) was the second son of Prince Itsarasunthon, son of Phutthayotfa Chulalok, the first Chakri king of Siam (King Rama I) and Princess Bunrot.[3] Mongkut was born in the Old (Thonburi) Palace in 1804, where the first son had died shortly after birth in 1801. He was followed by Prince Chutamani (เจ้าฟ้าจุฑามณี) in 1808. In 1809, Prince Itsarasunthon was crowned as Phutthaloetla Naphalai (later styled King Rama II.) The royal family then moved to the Grand Palace. Thenceforth, until their own accessions as kings, the brothers (เจ้าฟ้า chaofa) were called Chao Fa Yai (เจ้าฟ้าใหญ่) and Chao Fa Noi (เจ้าฟ้าน้อย).[4]: 151

Monastic life and Dhammayut sect

[edit]

In 1824, Mongkut became a Buddhist monk (ordination name Vajirayan; Pali Vajirañāṇo), following a Siamese tradition that men aged 20 should become monks for a time. The same year, his father died. By tradition, Mongkut should have been crowned the next king, but the nobility instead chose the older, more influential and experienced Prince Chetsadabodin (Nangklao), son of a royal concubine rather than a queen. Perceiving the throne was irredeemable and to avoid political intrigues, Mongkut retained his monastic status.

Vajirayan became one of the few members of the royal family who devoted his life to religion. He travelled around the country as a monk and saw the relaxation of the rules of the Pali Canon among the Siamese monks he met, which he considered inappropriate. In 1829, at Phetchaburi, he met a monk named Buddhawangso, who strictly followed the monastic rules of discipline, the vinaya. Vajirayan admired Buddhawangso for his obedience to the vinaya, and was inspired to pursue religious reforms.

In 1835, he began a reform movement reinforcing the vinaya law that evolved into the Dhammayuttika Nikaya, or Dhammayut sect. A strong theme in Mongkut's movement was that, "…true Buddhism was supposed to refrain from worldly matters and confine itself to spiritual and moral affairs".[5] Mongkut eventually came to power in 1851, as did his colleagues who had the same progressive mission. From that point on, Siam more quickly embraced modernization.[6] Vajirayan initiated two major revolutionary changes. Firstly, he embraced modern geography, among other sciences considered "Western". Secondly, he sought reform in Buddhism and, as a result, a new sect was created in Siamese Theravada Buddhism. Both revolutions challenged the purity and validity of the Buddhist order as it was practiced in Siam at the time.[5]

In 1836, Vajirayan arrived at Wat Bowonniwet in what is now Bangkok's central district, but was then the city proper, and became the wat's first abbot (เจ้าอาวาส). During this time, he pursued a Western education, studying Latin, English, and astronomy with missionaries and sailors. Vicar Pallegoix of the Roman Catholic Archdiocese of Bangkok lived nearby; the two became close friends, and Vajirayan invited Pallegoix to preach Christian sermons in the wat. Vajirayan admired Christian morals and achievements as presented by the vicar, but could make nothing of Christian doctrine. It was then that he made the comment later attributed to him as king: "What you teach people to do is admirable, but what you teach them to believe is foolish."[7]

King Mongkut would later be noted for his excellent command of English, although it is said that his younger brother, Viceroy Pinklao, could speak it even better. Mongkut's first son and heir, Chulalongkorn, granted the Thammayut sect royal recognition in 1902 through the Ecclesiastical Polity Act; it became one of the two major Buddhist denominations in modern Thailand.

Chulalongkorn also persuaded his father's 47th child, Vajirañana, to enter the order and he rose to become the 10th Supreme Patriarch of Thailand from 1910 to 1921.

Reign as king

[edit]

Accounts vary about Nangklao's intentions regarding the succession. It is recorded that Nangklao verbally dismissed the royal princes from succession for various reasons; Prince Mongkut was dismissed for encouraging monks to dress in the Mon style.

Prince Mongkut was supported by the pro-British Dit Bunnag who was the Samuha Kalahom, or Armed Force Department's president, and the most powerful noble during the reign of Rama III. He also had the support of British merchants who feared the growing anti-Western sentiment of the previous monarch and saw the 'prince monk' Mongkut as the 'champion' of European influence among the royal elite.

Bunnag, with the supporting promise of British agents, sent his men to the leaving-from-monk-status ceremony for Prince Mongkut even before Nangklao's death. With the support of powerful nobility and Britain, Mongkut's ascension to the throne was ensured.

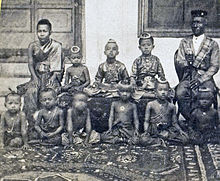

After his twenty-seven years of monastic life, King Mongkut voluntarily defrocked and ascended the throne in 1851, aged 47. He took the name Phra Chom Klao, although foreigners continued to call him King Mongkut. The king was well known among the foreigners, particularly some British officers, as pro-British. Sir James Brooke, a British delegate, even praised him as "our own king", and showed his support of him as a new king of Siam.[8] Having been celibate for 27 years, he now set about building the biggest royal family of the Chakri dynasty. Inside the palace there was a large number of women—reports say three thousand or more. They were mostly servants, guards, officials, maids and so on, but Mongkut acquired 32 wives, and by the time he died, aged 64, he had 82 children.[7]

His awareness of possibility of an outbreak of war with the European powers led him to institute many innovative activities. He ordered the nobility to wear shirts while attending his court; this was to show that Siam was a "modern" nation from the Western point of view.[note 1]

However, Mongkut's own astrological calculations pointed out that his brother, Prince Isaret, was as well-favored as himself to be the monarch. So, Mongkut then crowned his brother as King Pinklao, the second king. As a prince, Pinklao was known for his abilities in foreign languages and relations. Mongkut also raised his supporter Dit Bunnag to Somdet Chao Phraya Borom Maha Prayurawongse (Somdet Chao Phraya was the highest rank of nobility on a par with royalty) and made him his regent kingdom-wide. Mongkut also appointed Dit Bunnag's brother, Tat Bunnag, as Somdet Chao Phraya Borom Maha Pichaiyat, as his regent in Bangkok. As a result, the administrative power of Siam rested largely in the hands of the two Bunnags, Dit and Tat.

Upon his coronation, Mongkut married his first wife, Queen Somanass. However, Queen Somanass died in the same year. He then married his half-grandniece, Mom Chao Rampoei Siriwongse, later Queen Debsirindra.

Shan campaigns

[edit]In 1849, there were upheavals in the Shan State of Kengtung and Chiang Hung kingdom in response to weakened Burmese influence. However, the two states then fought each other and Chiang Hung sought Siamese support. Nangklao saw this as an opportunity to gain control over Shan states but he died in 1851 before this plan was realized. In 1852, Chiang Hung submitted the request again. Mongkut sent Siamese troops northwards but the armies were turned aside by the mountainous highlands. In 1855 the Siamese marched again and reached Kengtung—though with even greater difficulty. They laid siege on Kengtung for 21 days.[9] However, the resources of the Siamese army ran out and the army had to retreat.

Cultural reforms

[edit]

Introduction of Western geography

[edit]| Monarchs of the Chakri dynasty | |

|---|---|

| Phutthayotfa Chulalok (Rama I) | |

| Phutthaloetla Naphalai (Rama II) | |

| Nangklao (Rama III) | |

| Mongkut (Rama IV) | |

| Chulalongkorn (Rama V) | |

| Vajiravudh (Rama VI) | |

| Prajadhipok (Rama VII) | |

| Ananda Mahidol (Rama VIII) | |

| Bhumibol Adulyadej (Rama IX) | |

| Vajiralongkorn (Rama X) | |

Accompanying the influx of Western visitors to Siam was the notion of a round earth. By many Siamese, this was difficult to accept, particularly by religious standards, because Buddhist scripture described the earth as being flat.[10] The Traiphum, which was a geo-astrological map created before the arrival of Westerners, described "…a path between two mountain ranges through which the stars, planets, moon and sun pass."[10] Religious scholars usually concluded that Buddhist scriptures "…were meant to be taken literally only when it came to matters of spiritual truth; details of natural science are revealed figuratively and allegorically."[10] Mongkut claimed to have abandoned the Traiphum cosmology before 1836.[11] He claimed that he already knew of the round state of earth 15 years before the arrival of American missionaries, but the debate about Earth's shape remained an issue for Siamese intellectuals throughout the 1800s.[12]

Education reforms

[edit]During his reign, Mongkut urged his royal relatives to have "a European-style education."[12] The missionaries, as teachers, taught modern geography and astronomy, among other subjects.[12] Six years after Mongkut's death, the first Thai-language geography book was published in 1874, called Phumanithet by J.W. Van Dyke.[13] However, geography was only taught in select schools, mainly those that were run by American missionaries with English programs for upper secondary students.[14] Thongchai Winichakul argues that Mongkut's efforts to popularize Western geography helped bring reform to education in Siam.

Social changes

[edit]

1852 saw an influx of English and American missionaries into Siam as Mongkut hired them to teach the English language to the princes. He also hired Western mercenaries to train Siamese troops in Western style. In Bangkok, American Dan Beach Bradley had already reformed the printing system and then resumed the publishing of Siam's first newspaper, the Bangkok Recorder. However, the missionaries were not as successful when it came to making religious conversions.

In 1852, he ordered the nobles of the court to wear upper garments. Previously, Siamese nobles were forbidden to wear any shirts to prevent them from hiding any weapons in it and met the king bare-chested. The practice was criticized by Westerners and so Mongkut ended it.

However, Mongkut did not abandon the traditional culture of Siam. For Buddhism, Mongkut pioneered the rehabilitation of various temples. He also began the Magha Puja (มาฆบูชา) festival in the full moon of the third lunar month, to celebrate Buddha's announcement of his main principles. He instigated the recompilation of Tripitaka in Siam according to Theravada traditions. He also formally established the Thammayut sect as a rightful branch of Theravada.

Mongkut also improved women's rights in Siam. He released a large number of royal concubines to find their own husbands, in contrast to how his story has been dramatized. He banned forced marriages of all kinds and the selling of one's wife to pay off a debt.

In contrast to the previous king, Nangklao, Mongkut didn't see the importance of sending envoys to the Qing dynasty court, as the mission symbolised Siam's subjection to the Qing emperors and because the Qing dynasty was then not so powerful as it had once been, as it was itself threatened by Western powers.

Bowring Treaty

[edit]

In 1854, John Bowring, the governor of Hong Kong in the name of Queen Victoria, came to Siam to negotiate a treaty. For the first time Siam had to deal seriously with international laws. Prayurawongse negotiated on the behalf of the Siamese. The result was the Bowring Treaty between the two nations.[7] The main principle of the treaty was to abolish the Royal Storage (พระคลังสินค้า), which since Ayutthaya's times held the monopoly on foreign trade. The Royal Storage had been the source of Ayutthaya's prosperity as it collected immense taxation on foreign traders, including the taxation according to the width of the galleon and the tithe. Western products had to go through a series of tax barriers to reach Siamese people.

The Europeans had been attempting to undo this monopoly for a long time but no serious measures had been taken. For Siamese people, trading with foreigners subjected them to severe punishment by the government. The taxation was partially reduced in the Burney Treaty. However, in the world of nineteenth-century liberalism, government control over trade was swiftly disappearing.

The abolition of such trade barriers replaced the previous system of Siamese commerce with free trade. Import taxation was reduced to 3% and could only be collected once. This was a blow to national revenue. However, this led to dramatic growth of commercial sectors as common people gained access to foreign trade. People rushed to acquire vast, previously empty fields to grow rice and the competition eventually resulted in the lands ending up in the hands of nobility.

The Bowring Treaty also had a legal impact. Due to the horror of the Nakorn Bala methods of torture in judicial proceedings, the British requested not to be tried under the Siamese system, securing a grant of extraterritoriality; British subjects in Siam were therefore subject only to British law, while the Siamese in Britain enjoyed no reciprocal privilege.

More treaties were then made with other powers, further undermining national revenue and legal rights. The Bowring treaty proved to be the economic and social revolution of Siam. Mongkut's reign saw immense commercial activities in Siam for the first time, which led to the introduction of coinage in 1860. The first industries in Siam were rice milling and sugar production. Infrastructure was improved; there was a great deal of paving of roads and canal digging—for transport and water reservoirs for plantations.

Anna Leonowens

[edit]

In 1862, following a recommendation by Tan Kim Ching in Singapore, the court hired an English woman named Anna Leonowens, whose influence was later the subject of great Thai controversy. It is still debated how much this affected the worldview of one of his sons, Prince Chulalongkorn, who succeeded to the throne. Around 1870, Leonowens wrote a memoir of her time as teacher, “The English Governess at the Siamese Court.” Author Margaret Langdon took this work, and interviews with Leonowens' descendants, to fill out and create the more fictionalized account, Anna and the King of Siam, in 1944, which was adapted for films and a musical.

Her story would become the inspiration for the Hollywood movies Anna and the King of Siam and Anna and the King as well as the Rodgers and Hammerstein musical The King and I and its subsequent film adaptation, which, because of their fictionalized historical references and perceived disrespectful treatment of King Mongkut, were initially banned in Thailand as the Thai government and people considered them to be lèse majesté. To clarify the historical record, well-known Thai intellectuals Seni and Kukrit Pramoj in 1948 wrote The King of Siam Speaks. The Pramoj brothers sent their manuscript to the American politician and diplomat Abbot Low Moffat[15] (1901–1996), who drew on it for his 1961 biography, Mongkut the King of Siam. Moffat donated the Pramoj manuscript to the United States Library of Congress in 1961.[16]

Anna claimed that her conversations with Prince Chulalongkorn about human freedom, and her relating to him the story of Uncle Tom's Cabin, became the inspiration for his abolition of slavery almost 40 years later. Slavery in Thailand was sometimes a voluntary alternative for individuals to be rid of social and financial obligations.[17] One could be punished for torturing slaves in Siam, and some slaves could buy their freedom. Some western scholars and observers have expressed the opinion that Siamese slaves were treated better than English servants.[18]

Death and legacy

[edit]The solar eclipse at Wakor

[edit]

During his monkhood, Mongkut studied both indigenous astrology and English texts on Western astronomy and mathematics, hence developing his skills in astronomical measurement.[19] One way that he honed his mastery of astronomy, aside from the accurate prediction of the solar eclipse of 18 August 1868 (Wakor solar eclipse), was changing the official Buddhist calendar, "which was seriously miscalculated and the times for auspicious moments were incorrect."[20]

In 1868, he invited high-ranking European and Siamese officials to accompany him to Wakor village in Prachuap Khiri Khan Province, south of Hua Hin,[21] where the solar eclipse that was to occur on 18 August could be best viewed as a total eclipse.[22] Sir Harry Ord, the British governor of the Straits Settlements from Singapore, was among those who were invited.[23] King Mongkut predicted the solar eclipse, at (in his own words) "East Greenwich longitude 99 degrees 42' and latitude North 11 degrees 39'." King Mongkut's calculations proved accurate.[22] When he made calculations on the Wakor solar eclipse that was to occur, he used the Thai system of measuring time ("mong" and "baht"), but he implemented the Western method of longitude and latitude when he determined where on Earth the eclipse would best be viewed.[24] Upon returning from his journey to Wakor, he condemned the court astrologers "for their...stupid statements because of their negligence of his detailed prediction and their inattention to measurement and calculation by modern instruments."[13]

During the expedition, King Mongkut and Prince Chulalongkorn were infected with malaria. The king died six weeks later in the capital, and was succeeded by his son, who survived malaria.[13]

It has been argued that the assimilation of Western geography and astronomy into 19th-century Siam "proved that Siam equalled the West in terms of knowledge, and therefore the imperialists' claim that Siam was uncivilized and had to be colonized was unreasonable."[25] This suggests that the Western form of these sciences may have saved Siam from actually being colonized by Western powers.

Elephant story

[edit]

Contrary to popular belief, King Mongkut did not offer a herd of war elephants to the US president Abraham Lincoln during the American Civil War for use against the Confederacy. He did, however, offer to send some domesticated elephants to US president James Buchanan, to use as beasts of burden and means of transportation. The royal letter of 14 February 1861, which was written before the Civil War had even started, took some time to arrive in Washington DC, and by the time it reached its destination, President Buchanan was no longer in office.[26] Lincoln, who succeeded Buchanan, is said to have been asked what the elephants could be used for, and in reply he said that he did not know, unless "they were used to stamp out the rebellion."[27] However, in his reply dated 3 February 1862,[28] Lincoln did not mention anything about the Civil War. The President merely politely declined to accept King Mongkut's proposal, explaining to the King that the American climate might not be suitable for elephants and that American steam engines could also be used as beasts of burden and means of transportation.[29][30]

A century later, during his state visit to the US, King Bhumibol Adulyadej of Thailand, who was Mongkut's great-grandson, referred to this event in his address before the US Congress on 29 June 1960. He said, "my great-grandfather offered to send the President and Congress elephants to be turned loose in the uncultivated land of America for breeding purposes. That offer was made with no other objective than to provide a friend with what he lacks, in the same spirit in which the American aid program is likewise offered."[31]

151834 Mongkut

[edit]The asteroid 151834 Mongkut is named in honour of the King and his contributions to astronomy and the modernization of Siam.[32]

Tributes and legacy

[edit]

The main hospital of Phetchaburi province, Phrachomklao Hospital, is named after the King.

-

Monument of King Rama IV at Khon Kaen University

-

Monument of King Rama IV at Saranrom Palace

Family

[edit]King Mongkut is one of the people with the most children in Thai history; he had 32 wives and concubines during his lifetime who produced at least 82 children,[33] one of whom was Chulalongkorn, who married four of his half sisters.

Ancestry

[edit]| Ancestors of Mongkut | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

See also

[edit]Notes

[edit]- ^ Accordingly, the Hollywood depiction of the bare-chested Kralahome (prime minister) in Anna and the King of Siam (1946) and Yul Brynner's shirtless King Mongkut in The King and I (1956) are not only historically inaccurate, but considered by Thais to be offensive to the memory of the reformist monarch.

References

[edit]Citations

[edit]- ^ "The real 'King and I' – the story of new Thai king's famous ancestor". Reuters. 3 May 2019. Retrieved 12 November 2023.

- ^ "In Remembrance of His Majesty King Mongkut (King Rama IV), 1 October – Assumption University of Thailand". www.au.edu. Retrieved 12 November 2023.

- ^ https://www.bic.moe.go.th/images/stories/pdf/His_Majesty_King_Mongkut.pdf [bare URL PDF]

- ^ Bradley, William Lee (1969). "The Accession of King Mongkut (Notes)" (PDF). Journal of the Siam Society. JSS Vol. 57.1f. Siam Heritage Trust. Retrieved 11 August 2013.

...alluding ... to the two Chau Fa's.

- ^ a b Winichakul 1997, p. 39

- ^ Winichakul 1997, p. 40

- ^ a b c Bruce, Robert (1969). "King Mongkut of Siam and His Treaty with Britain" (PDF). Journal of the Royal Asiatic Society Hong Kong Branch. The University of Hong Kong Libraries Vol. 9. Retrieved 27 June 2011.

- ^ Tarling, Nicholas. The Cambridge History of Southeast Asia vol. 1 part 1, 1999. p. 44.

- ^ "การสงครามกับพม่าในสมัยรัชกาลที่ ๔,สมัยกรุงรัตนโกสินทร์,ประวัติศาสตร์ไทย, Historical Thailand, Thailand2000-2009, Thailand 2000–2003, sunthai group 2003, thailand2003, lions club thailnd2003, we serve, YE_MD310,โครงการแลกเปลี่ยนเยาวชนสโมสรไลออนส์ภาครวม 310 ประเทศไทย, Chinese Zodiac Prediction Science Thailand". Archived from the original on 28 February 2009. Retrieved 16 May 2009.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: unfit URL (link) - ^ a b c Suárez, Thomas. Early Mapping of Southeast Asia: The Epic Story of Seafarers, Adventurers, and Cartographers Who First Mapped the Regions Between China and India. Singapore: Periplus Editions (HK) Ltd. (1999). Web. p. 25

- ^ Winichakul 1997, p. 37

- ^ a b c Winichakul 1997, p. 38

- ^ a b c Winichakul 1997, p. 47

- ^ Winichakul 1997, p. 48

- ^ Abbot Low Moffat

- ^ "Southeast Asia and the Pacific Islands : Asian Collections: An Illustrated Guide (Library of Congress – Asian Division)". Library of Congress. Archived from the original on 23 October 2012. Retrieved 24 August 2013. (Southeast Asian Collection, Asian Division, Library of Congress)

- ^ Rodriguez, Junius P. (1997). The historical encyclopedia of world slavery (2nd print. ed.). Santa Barbara, Calif.: ABC-CLIO. p. 631. ISBN 9780874368857.

- ^ "Slavery in Nineteenth Century Northern Thailand: Archival Anecdotes and Village Voices". Kyoto Review. 2006. Archived from the original on 26 June 2007.

- ^ Winichakul 1997, p.42

- ^ Winichakul 1997, p. 43

- ^ Orchiston, Wayne (2019). "The Role of Eclipses and European Observers in the Development of 'Modern Astronomy' in Thailand". The Growth and Development of Astronomy and Astrophysics in India and the Asia-Pacific Region. Astrophysics and Space Science Proceedings. Vol. 54. p. 193. Bibcode:2019ASSP...54..173O. doi:10.1007/978-981-13-3645-4_14. ISBN 978-981-13-3644-7. S2CID 198775030.

- ^ a b Winichakul 1997, p. 46

- ^ Espenak, F. "NASA – Solar Eclipses of History". eclipse.gsfc.nasa.gov.

- ^ Winichakul 1997, p. 45

- ^ Winichakul 1997, p. 57

- ^ "Nontraditional Animals For Use by the American Military – Elephants". Newsletter. HistoryBuff.com. June 2011. Archived from the original on 4 May 2012. Retrieved 29 May 2012.

Both original letters still exist today in archives.

- ^ The ivory king : A popular history of the elephant and its allies. 1902. ISBN 9780836991413.

- ^ "The Lincoln Log". www.thelincolnlog.org. Archived from the original on 16 July 2011. Retrieved 15 January 2022.

- ^ "Council of American Ambassadors > Publications > the Ambassadors Review > Setting the Stage for the Next 175 Years: United States and Thai Relations Renewed". Archived from the original on 31 August 2009. Retrieved 6 August 2009.

- ^ "Press Release nr99-122". 15 August 2016.

- ^ "Archived copy". www.ohmpps.go.th. Archived from the original on 3 May 2009. Retrieved 15 January 2022.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) - ^ "IAU Minor Planet Center". NASA. Retrieved 19 February 2015.

- ^ Christopher John Baker; Pasuk Phongpaichit (2009). A History of Thailand. Cambridge University Press. p. 31. ISBN 978-0-521-76768-2. Retrieved 9 August 2016.

Sources

[edit]- Abbot Low Moffat, Mongkhut, the King of Siam, Cornell U.P. 1961

- Constance Marilyn Wilson, State and Society in the Reign of King Mongkut, 1851–1868: Thailand on the Eve of Modernization, Ph.D. thesis, Cornell 1970, University Microfilms.

- B. J. Terwiel, A History of Modern Thailand 1767–1942, University of Queensland Press, Australia 1983. This contains some anecdotes not included in the other references.

- Stephen White, John Thomson: A Window to the Orient, University of New Mexico Press, United States. Thomson was a photographer and this book contains his pictures some of which provided the basis for the engravings (sometimes misidentified) in Anna Leonowens' books. There is reference to Mongkut in the introductory text.

- Suárez, Thomas. Early Mapping of Southeast Asia: The Epic Story of Seafarers, Adventurers, and Cartographers Who First Mapped the Regions Between China and India. Singapore: Periplus Editions (HK) Ltd. (1999). p. 25

- Winichakul, Thongchai. Siam Mapped: A History of the Geo-Body of a Nation. Various pages from Chapter 2. University of Hawaii Press (1997).

External links

[edit]- The King's Thai: Entry to Thai Historical Data – Mongkut's Edicts maintained by Doug Cooper of Center for Research in Computational Linguistics, Bangkok; accessed 2008-07-11.

- Mongkut

- Thai people of Mon descent

- Rattanakosin Kingdom

- 1804 births

- 1868 deaths

- 19th-century Chakri dynasty

- 19th-century Thai monarchs

- 19th-century monarchs in Asia

- Deaths from malaria

- Thai Theravada Buddhists

- 1850s in Siam

- 1860s in Siam

- Grand Cross of the Legion of Honour

- Founders of Buddhist sects

- Thai male Chao Fa