USS Los Angeles (ZR-3)

| USS Los Angeles (ZR-3) | |

|---|---|

Los Angeles at the mooring mast on the tender USS Patoka | |

| General information | |

| Manufacturer | Luftschiffbau Zeppelin, Friedrichshafen |

| Construction number | LZ-126 |

| Serial | ZR-3 |

| History | |

| Manufactured | July 1922 (Commenced) August 1924 (Launched) |

| In service | 25 November 1924 (Commissioned) 30 June 1932 (Decommissioned) 24 October 1939 (Struck from Naval Register) |

| Fate | Broken up for scrap in 1939 |

USS Los Angeles was a rigid airship, designated ZR-3, which was built in 1923–1924 by the Zeppelin company in Friedrichshafen, Germany, as war reparations. She was delivered to the United States Navy in October 1924 and after being used mainly for experimental work, particularly in the development of the American parasite fighter program, was decommissioned in 1932.

Design

[edit]The second of four vessels to carry the name USS Los Angeles, the airship was built for the United States Navy as a replacement for the Zeppelins that had been assigned to the United States as war reparations following World War I, and had been sabotaged by their crews in 1919.[1] Under the terms of the Treaty of Versailles Luftschiffbau Zeppelin were not permitted to build military airships. In consequence Los Angeles, which had the Zeppelin works number LZ 126, was built as a passenger airship, although the treaty limitation on the permissible volume was waived, it being agreed that a craft of a size equal to the largest Zeppelin constructed during World War I was permissible.[2]

The airship's hull had 24-sided transverse ring frames for most of its length, changing to an octagonal section at the tail surfaces, and the hull had an internal keel which provided an internal walkway and also contained the accommodation for the crew when off duty. For most of the ship's length the main frames were 32 feet 10 inches (10.01 m) apart, with two secondary frames in each bay. Following the precedent set by LZ 120 Bodensee, crew and passenger accommodation was in a compartment near the front of the airship that was integrated into the hull structure. Each of the five Maybach VL I V12 engines occupied a separate engine car, arranged as four wing cars with the fifth aft on the centerline of the ship. All drove two-bladed pusher propellers and were capable of running in reverse. Auxiliary power was provided by wind-driven dynamos.[2]

Operational history

[edit]

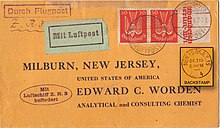

Los Angeles was first flown on 27 August 1924. After completing flight trials, she began the transatlantic delivery flight to the U.S. on 12 October 1924 under the command of Hugo Eckener, arriving at the U.S. Naval Air Station at Lakehurst, New Jersey, after an 81-hour flight of 4,229 nautical miles (7,832 km; 4,867 mi).[1][3] The airship was commissioned into the U.S. Navy on 25 November 1924 at Naval Support Facility Anacostia at Washington, D.C. with Lieutenant Commander Maurice R. Pierce in command. On her arrival in the United States, her lifting gas was changed from hydrogen to helium, which reduced payload but improved safety. At the same time the airship was fitted with equipment to recover water from the exhaust gases for use as ballast to compensate for the loss of weight as fuel was consumed, so avoiding the necessity to vent scarce helium to maintain neutral buoyancy.[1]

The airship went on to log a total of 4,398 hours of flight, covering a distance of 172,400 nautical miles (319,300 km; 198,400 mi). Long-distance flights included return flights to Panama, Costa Rica and Bermuda.[1][4] She served as an observatory and experimental platform, as well as a training ship for other airships.

On 24 January 1925, U.S. Naval Observatory and U.S. Bureau of Standards gathered a group of astronomers to observe a total solar eclipse from the airship over the New York City, with Captain Edwin Taylor Pollock as a head of the group.[5][6] They used "two pairs of telescopic cameras", to capture inner and outer portions of Sun's corona, and a spectrograph. The expedition achieved good publicity, but it was not very successful in its observations - the dirigible was not very stable and the photos were blurred.[7]

On 25 August 1927, while Los Angeles was tethered at the Lakehurst high mast, a gust of wind caught her tail and lifted it into colder, denser air that was just above the airship. This caused the tail to lift higher. The crew on board tried to compensate by climbing up the keel toward the rising tail, but could not stop the ship from reaching an angle of 85 degrees, before it descended. The ship suffered only slight damage and was able to fly the next day.

In 1929, Los Angeles was used to test the trapeze system developed by the U.S. Navy to launch and recover fixed wing aircraft from rigid airships. The tests were a success and the later purpose-built Akron-class airships were fitted with this system.[1] The temporary system was removed from Los Angeles, which never carried any aircraft on operational flights.[8] On 31 January 1930, Los Angeles also tested the launching of a glider over Lakehurst, New Jersey.[9][10]

On 25 May 1932, Los Angeles participated in a demonstration of photophone technology. Floating over the General Electric plant in Schenectady, New York, the crew of the ship engaged in an on-air conversation with a WGY radio announcer using a beam of light.[11]

As the terms under which the Allies permitted the United States to have Los Angeles restricted her use to commercial and experimental purposes only, when the U.S. Navy wanted to use the airship in a fleet problem in 1931 permission had to be obtained from the Allied Control Commission.[12] Los Angeles took part in Fleet Problems XII (1931) and XIII (1932), although as was the case with all U.S. Navy rigid airships, demonstrated no particular benefit to the fleet.[13]

Los Angeles was decommissioned in 1932 as an economy measure, but was recommissioned after the crash of USS Akron in April 1933. She flew for a few more years and then retired to her Lakehurst hangar where she remained until 1939, when the airship was struck off the Navy list and was dismantled in her hangar. Los Angeles was the Navy's longest-serving rigid airship. Unlike Shenandoah, R38, Akron, and Macon, the German-built Los Angeles was the only Navy rigid airship which did not meet a disastrous end.

Gallery

[edit]-

LZ 126 over Berlin, 1924

-

USS Los Angeles in Panama, 1929

-

Passenger cabin of the airship, 1924

-

USS Los Angeles lofted nearly vertical during the weather-related docking-mast mishap in August, 1927.

-

An RRG Prüfling glider attached to USS Los Angeles for carriage and drop tests.

-

USS Los Angeles anchored to USS Saratoga (CV-3).

-

USS Los Angeles over Manhattan, New York, 1930

-

USS Los Angeles in Panama 1929

-

USS Los Angeles in flight

-

USS Los Angeles, USS Patoka and USS Lexington off Panama City, Panama, about 1931

-

USS Los Angeles flies past the U.S. Capitol

-

USS Los Angeles enters storage hangar for the first time at Naval Air Station, Lakehurst, New Jersey, in 1924

-

Z.R. 3 in America - Special sheet of the Dresdner Anzeiger

Notes

[edit]- ^ a b c d e "Kite Balloons to Airships...the Navy's Lighter-than-Air Experience" (PDF). Naval History and Heritage Command. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2014-04-10. Retrieved 2014-02-25.

- ^ a b "America's Second Rigid Airship—"ZR 3"". Flight International: 60. 31 January 1924.

- ^ Althoff 2004, pp. 33–42.

- ^ Moffett, William A. (1 December 1928). "Liners of The Air". Liberty Magazine: 21.

- ^ LaFollette, Marcel Chotkowski (24 January 2017). "Science Service, Up Close: Up in the Air for a Solar Eclipse". Smithsonian Institution Archives. Retrieved 9 January 2024.

- ^ Maloney, Wendi A. (21 August 2017). "Looking to the Sky: Solar Eclipse 2017 | Timeless". The Library of Congress. Retrieved 9 January 2024.

- ^ Aceto, Guy (26 January 2022). "To Catch a Shadow: The Great 1925 Solar Eclipse Aerial Expedition". HistoryNet. Retrieved 9 January 2024.

- ^ "Big Changes Give Giants Of The Air Far Wider Range". Popular Science Monthly. Vol. 117, no. 3. New York: Popular Science Publishing Company. September 1930. p. 51.

- ^ "Glider Lands From Airship". The San Bernardino Daily Sun. Vol. 65. San Bernardino, California. Associated Press. 1 February 1930. p. 1.

- ^ "Dirigible Launches Glider". Popular Mechanics. Vol. 53, no. 4. Chicago, Illinois: Popular Mechanics Company. April 1930. p. 80.

- ^ Hart 1992, pp. 42–43.

- ^ "Allies Permit the Navy to Use The Los Angeles in War Game". The New York Times. 8 January 1931.

- ^ Behrends, Werner The Great Airships of Count Zeppelin (2015) Raleigh, NC: Lulu.com, p. 102

Bibliography

[edit]- Althoff, William F. Sky Ships. New York: Orion Books, 1990. ISBN 0-517-56904-3.

- Althoff, William F. USS Los Angeles: The Navy's Venerable Airship and Aviation Technology. Dulles, Virginia: Brassey's, 2004. ISBN 1-57488-620-7.

- Hart, Larry. Pictures From the Past: A Schenectady Album. Schenectady, New York: Old Dorp Books, 1992. ISBN 978-0-932035-13-4.

- Provan, John. LZ-127 "Graf Zeppelin": The story of an Airship, vol. 1 & vol. 2 (Amazon Kindle ebook). Pueblo, Colorado: Luftschiff Zeppelin Collection, 2011.

- Robinson, Douglas H., and Charles L. Keller. "Up Ship!": U.S. Navy Rigid Airships 1919–1935. Annapolis, Maryland: Naval Institute Press, 1982. ISBN 0-87021-738-0.

External links

[edit]- Photo gallery of USS Los Angeles

- eZEP.de – a dedicated web portal for Zeppelin mail and airship memorabilia

- Zeppelin Study Group – a research group for airship memorabilia and Zeppelin mail

- USS Los Angeles (ZR-3) – page at Navy Lakehurst Historical Society

- Picture of the 25 August 1927 nose stand

- DANFS article on Los Angeles (ZR-3)

- Photo gallery at Naval Historical Center

- 1925 eclipse footage shot from ship

- "Queen of Dirigibles Ready for U.S." May 1924, Popular Science Monthly – excellent drawing showing size comparison between earlier dirigibles and battleships

- "Flying with an Airship Captain" Mar 1930, Popular Science Monthly – Article detailing the operation of Los Angeles