Kindertransport

The Kindertransport (German for "children's transport") was an organised rescue effort of children from Nazi-controlled territory that took place in 1938–1939 during the nine months prior to the outbreak of the Second World War. The United Kingdom took in nearly 10,000 children,[1] most of them Jewish, from Germany, Austria, Czechoslovakia, Poland, and the Free City of Danzig. The children were placed in British foster homes, hostels, schools, and farms. Often they were the only members of their families who survived the Holocaust. The programme was supported, publicised, and encouraged by the British government, which waived the visa immigration requirements that were not within the ability of the British Jewish community to fulfil.[2][3] The British government placed no numerical limit on the programme; it was the start of the Second World War that brought it to an end, by which time about 10,000 kindertransport children had been brought to the country.

Smaller numbers of children were taken in via the programme by the Netherlands, Belgium, France, Sweden, and Switzerland.[4][5][6] The term "kindertransport" may also be applied to the rescue of mainly Jewish children from Nazi German territory to the Netherlands, Belgium, and France. An example is the 1,000 Chateau de La Hille children who went to Belgium.[3][7] However, most often the term is restricted to the organised programme of the United Kingdom.

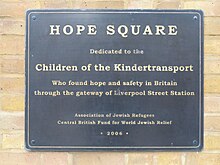

The Central British Fund for German Jewry (now World Jewish Relief) was established in 1933 to support in whatever way possible the needs of Jews in Germany and Austria.

In the United States, the Wagner–Rogers Bill was introduced in Congress, which would have increased the quota of immigrants by bringing to the U.S. a total of 20,000 refugee children, but it did not pass.

Policy

[edit]On 15 November 1938, five days after the devastation of Kristallnacht, the "Night of Broken Glass", in Germany and Austria, a delegation of British, Jewish, and Quaker leaders appealed, in person, to the Prime Minister of the United Kingdom, Neville Chamberlain.[8] Among other measures, they requested that the British government permit the temporary admission of unaccompanied Jewish children, without their parents.

The British Cabinet debated the issue the next day and subsequently prepared a bill to present to Parliament.[9] The bill stated that the government would waive certain immigration requirements so as to allow the entry into Great Britain of unaccompanied children ranging from infants up to the age of 17, under a number of conditions.

No limit upon the permitted number of refugees was ever publicly announced. Initially, the Jewish refugee agencies considered 5,000 as a realistic target goal. However, after the British Colonial Office turned down the Jewish agencies' separate request to allow the admission of 10,000 children to British-controlled Mandatory Palestine, the Jewish agencies then increased their planned target number to 15,000 unaccompanied children to enter Great Britain in this way.[citation needed]

During the morning of 21 November 1938, before a major House of Commons debate on refugees, the Home Secretary, Sir Samuel Hoare met a large delegation representing Jewish and Quaker groups, as well as other groups, working on behalf of refugees. In what was described by Rose Holmes as a "watershed moment" the government accepted "the political recommendation of a coalition of voluntary agencies" but without accepting that the government had any administrative or financial responsibility.[10] The groups, though considering all refugees, were allied under a non-denominational organisation called the "Movement for the Care of Children from Germany".[11] This organisation was considering only the rescue of children, who would need to leave their parents behind in Germany.

In that debate of 21 November 1938, Hoare paid particular attention to the plight of children.[12] He reported that enquiries in Germany had determined that nearly every parent asked had said that they would be willing to send their child off unaccompanied to the United Kingdom, leaving their parents behind.[13][a]

Although Hoare declared that he and the Home Office "shall put no obstacle in the way of children coming here," the agencies involved had to find homes for the children and also fund the operation to ensure that none of the refugees would become a financial burden on the public. Every child had to have a guarantee of £50 sterling to finance his or her eventual re-emigration, as it was expected the children would stay in the country only temporarily.[14] Hoare made it clear that the monetary and housing and other aid required had been promised by the Jewish community and other communities.[12]

Organisation and management

[edit]

Vienna, Westbahnhof Station 2008, a tribute to the British people for saving the lives of thousands of children from Nazi terror through the Kindertransports

Within a short time, the Movement for the Care of Children from Germany, later known as the Refugee Children's Movement (RCM), sent representatives to Germany and Austria to establish the systems for choosing, organising, and transporting the children. The Central British Fund for German Jewry provided funding for the rescue operation.[16]

On 25 November, British citizens heard an appeal for foster homes on the BBC Home Service radio station from former Home Secretary Viscount Samuel. Soon there were 500 offers, and RCM volunteers started visiting possible foster homes and reporting on conditions. They did not insist that the homes for Jewish children should be Jewish homes. Nor did they probe too carefully into the motives and character of the families: it was sufficient for the houses to look clean and the families to seem respectable.[17]

In Germany, a network of organisers was established, and these volunteers worked around the clock to make priority lists of those most in peril: teenagers who were in concentration camps or in danger of arrest, Polish children or teenagers threatened with deportation, children in Jewish orphanages, children whose parents were too impoverished to keep them, or children with a parent in a concentration camp. Once the children were identified or grouped by list, their guardians or parents were issued a travel date and departure details. They could only take a small sealed suitcase with no valuables and only ten marks or less in money. Some children had nothing but a manila tag with a number on the front and their name on the back,[18] others were issued with a numbered identity card with a photo:[19]

The first party of 196 children arrived at Harwich on the TSS Prague on 2 December, three weeks after Kristallnacht, disembarking at Parkeston Quay.[20][21] A plaque unveiled in 2011 at Harwich harbour marks this event.[21]

In the following nine months almost 10,000 unaccompanied children, mainly Jewish, travelled to England.[22]

There were also Kindertransports to other countries, such as France, Belgium, the Netherlands, Sweden and Denmark. Dutch humanitarian Geertruida Wijsmuller-Meijer arranged for 1,500 children to be admitted to the Netherlands; the children were supported by the Dutch Committee for Jewish Refugees, which was paid by the Dutch Jewish Community.[23] In Sweden, the Jewish Community of Stockholm negotiated with the government for an exception to the country's restrictive policy on Jewish refugees for a number of children. Eventually around 500 Jewish children from Germany aged between 1 and 15 were granted temporary residence permits on the condition that their parents would not try to enter the country. The children were selected by Jewish organisations in Germany and placed in foster homes and orphanages in Sweden.[24]

Initially the children came mainly from Germany and Austria (part of the Greater Reich after Anschluss). From 15 March 1939, with the German occupation of Czechoslovakia, transports from Prague were hastily organised. In February and August 1939, trains from Poland were arranged. Transports out of Nazi-occupied Europe continued until the declaration of war on 1 September 1939.

A smaller number of children flew to Croydon Airport, mainly from Prague.[25] Other ports in England receiving the children included Dover.[25][26]

Last transport

[edit]

The last transport from the continent with 74 children left on the passenger-freighter SS Bodegraven on 14 May 1940, from IJmuiden, Netherlands. Their departure was organised by Geertruida Wijsmuller-Meijer, the Dutch organiser of the first transport from Vienna in December 1938. She had collected 66 of the children from the orphanage on the Kalverstraat in Amsterdam, part of which had been serving as a home for refugees.[27] She could have joined the children, but chose to remain behind.[28] This was a rescue action, as occupation of the Netherlands was imminent, with the country capitulating the next day. This ship was the last to leave the country freely.

As the Netherlands was under attack by German forces from 10 May and bombing had been going on, there was no opportunity to confer with the parents of the children. At the time of this evacuation, these parents knew nothing of the evacuation of their children: according to unnamed sources, some of the parents were initially very upset about this action and told Wijsmuller-Meijer that she should not have done this.[citation needed] After 15 May, there was no more opportunity to leave the Netherlands as the country's borders were closed by the Nazis.

Trauma suffered by the children

[edit]This section needs additional citations for verification. (August 2022) |

Many children went through trauma during their extensive Kindertransport experience.[citation needed] Reports of this trauma is often presented in personal terms, with trauma varying based on the child's experiences, including their age at separation from their parents, their experience during the wartime, and their experience after the war.

The primary trauma experienced by children in the Kindertransport was the separation from their parents. Depending on the child's age, the explanation for why they were leaving the country and their parents differed widely: for example, children might be told "you are going on an exciting adventure", or "you are going on a short trip and we will see you soon". Young children, roughly six or younger, would generally not accept such an explanation and would demand to stay with their parents.

Older children, who were "more willing to accept the parents' explanation", would nevertheless realise that they would be separated from their parents for a long or indefinite period of time; younger children, in contrast, who had no developed sense of time, would not be able to comprehend that they may see their parents again, thus making the trauma of separation total from the beginning. The actual leaving, via railway station, was also not a peaceful process, and there are many records[where?] of tears and screaming at the various railway stations where the actual parting took place.

Having to learn a new language, in a country where the child's native German or Czech was not understood, was another cause of stress. To have to learn to live with strangers, who only spoke English, and accept them as "pseudo-parents", was a trauma. At school, the English children would often view the refugee children as "enemy Germans" instead of "Jewish refugees".

Before the war started on 1 September 1939, and even during the first part of the war, some parents were able to escape from Hitler and reach England and then reunite with their children. However, this became the exception, as most of the parents of the refugee children were murdered by the Nazis.[citation needed]

Older refugee children became fully aware of the war in Europe during the period of 1939–1945 and would become concerned for their parents. During the latter years of the war, they may have become aware of the Holocaust and the actual direct threat to their Jewish parents and extended family. After the war ended in 1945, nearly all the children learned, sooner or later, that their parents had been murdered.[29][30]

In November 2018, for the 80th anniversary of the Kindertransport programme, the German government announced that it would make a payment of €2,500 (about US$2,800 at the time) to each of the "Kinder" who was still alive.[31] This payment, although a token amount, represented an explicit recognition and acceptance of the immense damage that had been done to each child, both psychological and material.

Transportation and programme completion

[edit]

The Nazis had decreed that the evacuations must not block ports in Germany, so most transport parties went by train to the Netherlands; then to a British port, generally Harwich, by ferry from the Hook of Holland near Rotterdam.[33] From the port, a train took some of the children to Liverpool Street station in London, where they were met by their volunteer foster parents. Children without prearranged foster families were sheltered at temporary holding centres at summer holiday camps such as Dovercourt and Pakefield, with the Broadreeds holiday camp, at Selsey, West Sussex, being used as a transit camp for girls.[34] While most transports went via train, some also went by boat,[35] and others aeroplane.[15]

The first Kindertransport was organised and masterminded by Florence Nankivell. She spent a week in Berlin, hassled by the Nazi police, organising the children. The train left Berlin on 1 December 1938, and arrived in Harwich on 2 December with 196 children. Most were from a Berlin Jewish orphanage burned by the Nazis during the night of 9 November, and the others were from Hamburg.[28][36]

The first train from Vienna left on 10 December 1938 with 600 children. This was the result of the work of Geertruida Wijsmuller-Meijer, a Dutch organiser of Kindertransports, who had been active in this field since 1933. She went to Vienna with the purpose of negotiating with Adolf Eichmann directly, but was initially turned away. She persevered however, until finally, as she wrote in her biography, Eichmann suddenly "gave" her 600 children with the clear intent of overloading her and making a transport on such short notice impossible. Nevertheless, Wijsmuller-Meijer managed to send 500 of the children to Harwich, where they were accommodated in a nearby holiday camp at Dovercourt, while the remaining 100 found refuge in the Netherlands.[7][37]

Many representatives went with the parties from Germany to the Netherlands, or met the parties at Liverpool Street station in London and ensured that there was someone there to receive and care for each child.[38][39][40][41] Between 1939 and 1941, 160 children without foster families were sent to the Whittingehame Farm School in East Lothian, Scotland. The Whittingehame estate was the family home of Arthur Balfour, former UK prime minister and, in 1917, author of the Balfour Declaration.[42]

The RCM ran out of money at the end of August 1939, and decided it could take no more children. The last group of children left Germany on 1 September 1939, the day Germany invaded Poland, and two days later Britain, France, and other countries declared war on Germany. A party left Prague on 3 September 1939, but was sent back.[43]

Sculpture groups on the Kindertransport route

[edit]Marking the European route of the children's transport and created from personal experience,[44] Frank Meisler's sculpture groups show similarities but with different details.[45] The memorials show two groups of children and young people standing with their backs to each other waiting for a train. Depicted in different colours, the group of the rescued is outnumbered, as the majority of Jewish children (more than one million) perished in the Nazi death camps.

- 2006: Kindertransport – The Arrival at the initiative of Prince Charles there is a monument to the Kindertransporten at London's Liverpool Street Station, where the children from Hook of Holland arrived.

- 2008: Children's Transport Monument. Züge ins Leben – Züge in den Tod: 1938–1939 (Trains to life – trains to death) at Berlin Friedrichstraße station for the rescue of 10,000 Jewish children, who travelled from here to London. The monument was unveiled on 30 November 2008.

- 2009: Kindertransport – Die Abreise (The Departure). At the request of the mayor of Gdańsk, Paweł Adamowicz, Frank Meisler designed another group of children's sculptures in May 2009, in memory of 124 departing children.

- 2011: Crossing Channel to life. Monument to the 10,000 Jewish children who travelled from Hook of Holland to Harwich. The newspaper De Rotterdammer of 11 November 1938 is depicted next to the sitting boy, with the messages The admission of German Jewish children and Thousands of Jews must leave Germany.

- 2015: Kindertransport – Der letzte Abschied (The last farewell), at Hamburg Dammtor station.

In September 2022 a bronze memorial entitled Safe Haven was unveiled on Harwich Quay by Dame Steve Shirley, a former Kindertransport child.[46] The work by artist Ian Wolter is a life-size, bronze sculpture of five Kindertransport refugees descending a ship's gangplank. Each child is portrayed with a different emotion representing the storm of emotions they must have felt at the end of their journey by train and then ship. The figures are also engraved with quotes of four of the refugees describing their first experience of the UK. The memorial is within sight of the landing place at Parkeston Quay of thousands of Kindertransport children.

-

Züge ins Leben – Züge in den Tod: 1938–1939 - Trains to Life – Trains to Death, Friedrichstraße station, Berlin

-

Die Abreise - The departure in front of Gdańsk Główny station

-

Kindertransport – Der letzte Abschied - The final parting, Hamburg Dammtor station

-

Harwich memorial Safe Haven by Ian Wolter

Habonim hostels

[edit]A number of members of Habonim, a Jewish youth movement inclined to socialism and Zionism, were instrumental in running the country hostels of South West England. These members of Habonim were held back from going to live on kibbutz by the war.[47]

Records

[edit]Records for many of the children who arrived in the UK through the Kindertransports are maintained by World Jewish Relief through its Jewish Refugees Committee.[16]

Recovery

[edit]At the end of the war, there were great difficulties in Britain as children from the Kindertransport tried to reunite with their families. Agencies were flooded with requests from children seeking to find their parents, or any surviving member of their family. Some of the children were able to reunite with their families, often travelling to far-off countries in order to do so. Others discovered that their parents had not survived the war. In her novel about the Kindertransport titled The Children of Willesden Lane, Mona Golabek describes how often the children who had no families left were forced to leave the homes that they had gained during the war in boarding houses in order to make room for younger children flooding the country.[48]

Nicholas Winton

[edit]Before Christmas 1938, Nicholas Winton, a 29-year-old British stockbroker of German-Jewish origin, travelled to Prague to help a friend involved in Jewish refugee work.[49] Under the loose direction of the British Committee for Refugees from Czechoslovakia, headed by Doreen Warriner, Winton spent three weeks in Prague compiling a list of children in Czechoslovakia, mostly Jewish, who were refugees from Nazi Germany. He then went back to Britain with the objective of fulfilling the legal requirements to bring the children to Britain and to find homes for them. Trevor Chadwick remained behind to head the children's programme in Czechoslovakia.[50][51] Winton's mother also worked with him to place the children in homes, and later hostels, with a team of sponsors from groups like Maidenhead Rotary Club and Rugby Refugee Committee.[43][52] Throughout the summer, he placed advertisements seeking British families to take them in. A total of 669 children were evacuated from Czechoslovakia to Britain in 1939 through the work of Chadwick, Warriner, Beatrice Wellington, Waitstill and Martha Sharp, Quaker volunteers such as Tessa Rowntree, and others who worked in Czechoslovakia while Winton was in Britain. The last group of children, which left Prague on 3 September 1939, was turned back because the Nazis had invaded Poland – the beginning of the Second World War.[43][53] The children travelled to Britain while their parents remained in Czechoslovakia. The settlement of the children in Britain without their parents was perceived at the time as a temporary measure but the war began.

The work of the BCRC in Czechoslovakia was little noted until 1988 when the refugee children held a reunion. By that time most of the people who had worked in the kindertransport in Czechoslovakia had died and Winton became the living symbol of British help to refugees fleeing the Nazis, especially Jewish refugees, before the Second World War.[54] Winton has been lionised by both the British and Czech governments "in part to reframe their national Holocaust histories more positively."[55] Latter-day historians have acknowledged the contribution of Winton, but characterised the kindertransport from Czechoslovakia as "a grassroots transnational network of escape...This network connected Boston-based Unitarians, London-based socialists, and Prague-based Jewish social workers in a complex web of interfaith refugee assistance."[56]

Wilfrid Israel

[edit]Wilfrid Israel (1899–1943) was a key figure in the rescue of Jews from Germany and occupied Europe. He warned the British government, through Lord Samuel, of the impending Kristallnacht in November 1938. Through a British agent, Frank Foley, passport officer at the Berlin consulate, he kept British intelligence informed of Nazi activities. Speaking on behalf of the Reichsvertretung (the German Jewish communal organisation) and the Hilfsverein (the self-help body), he urged a plan of rescue on the Foreign Office and helped British Quakers to visit Jewish communities across Germany to prove to the British government that Jewish parents were indeed prepared to part with their children.[57]

Rabbi Solomon Schonfeld

[edit]Rabbi Solomon Schonfeld brought in 300 children who practised Orthodox Judaism, under auspices of the Chief Rabbi's Religious Emergency Council. He housed many of them in his London home for a while. During the Blitz he found for them in the countryside often non-Jewish foster homes. In order to ensure that the children followed Jewish dietary laws (Kashrut), he instructed them to say to the foster parents that they were fish-eating vegetarians. He also saved large numbers of Jews with South American protection papers. He brought over to England several thousand young people, rabbis, teachers, ritual slaughterers, and other religious functionaries.[58]

Internment and war service

[edit]

In June 1940, Winston Churchill, the British Prime Minister, ordered the internment of all male 16-to 70-year-old refugees from enemy countries – so-called 'friendly enemy aliens'. A complete history of this internment episode is given in the book Collar the Lot!.[59]

Many of the children who had arrived in earlier years were now young men, and so they were also interned. Approximately 1,000 of these prior-kinder were interned in these internment camps, many on the Isle of Man. Around 400 were transported overseas to Canada and Australia (see HMT Dunera).

The fast, unescorted liner, SS Arandora Star was sunk by German submarine U-47 on 2 July 1940. Many of her 1213 German, Italian, and Austrian refugees, and internees (she was also carrying 86 German POWs) were ex-Kindertransport children. There was difficulty launching the lifeboats, and as a result, 805 people died out of the original complement of 1673. This led to evacuations of British children on passenger liners under the Children's Overseas Reception Board and the United States Committee for the Care of European Children to be protected by convoys.[citation needed]

As the camp internees reached the age of 18, they were offered the chance to do war work or to enter the Army Auxiliary Pioneer Corps. About 1,000 German and Austrian prior-kinder who reached adulthood went on to serve in the British armed forces, including in combat units. Several dozen joined elite formations such as the Special Forces, where their language skills were put to good use during the Normandy landings, and afterwards as the Allies progressed into Germany. One of these was Peter Masters, who wrote a book which he titled Striking Back.[60]

Most of the interned 'friendly enemy aliens' were refugees who had fled Hitler and Nazism, and nearly all were Jewish.[citation needed] When Churchill's internment policy became known, there was a debate in Parliament. Many speeches expressed horror at the idea of interning refugees, and a vote overwhelmingly instructed the Government to "undo" the internment.[59]

United Kingdom and the United States

[edit]In contrast to the Kindertransport, where the British Government waived immigration visa requirements, these OTC children received no United States government visa immigration assistance. The U.S. government made it difficult for refugees to get entrance visas.[61] However, from 1933 to 1945, the United States accepted about 200,000 refugees fleeing Nazism, more than any other country. Most of the refugees were Jewish.[62]

In 1939 Senator Robert F. Wagner and Rep. Edith Rogers proposed the Wagner-Rogers Bill in the United States Congress. This bill was to admit 20,000 unaccompanied refugees under the age of 14 into the United States from Germany and areas under German control. Most of the child refugees would have been Jewish. However, due to opposition from Senator Robert Rice Reynolds, it never left the committee stage and failed to get Congressional approval.[63]

Notable people saved

[edit]

A number of children saved by the Kindertransports went on to become prominent figures in public life, with two (Walter Kohn, Arno Penzias) becoming Nobel Prize winners. These include:

- Benjamin Abeles (from Czechoslovakia), physicist

- Yosef Alon (from Czechoslovakia), Israeli military officer and fighter pilot who served as air and naval attaché to the United States, assassinated under suspicious circumstances in Maryland in 1973.

- Alfred Bader (from Austria), Canadian chemist, businessman, and philanthropist

- Ruth Barnett MBE (from Germany), British writer

- Leslie Brent MBE (from Germany), British immunologist

- Julius Carlebach (from Germany), British sociologist, historian and rabbi

- Paul Moritz Cohn (from Germany), British mathematician, Fellow of the Royal Society

- Rolf Decker (from Germany), American professional, Olympic, and international footballer

- Alfred Dubs, Baron Dubs (from Czechoslovakia), British politician

- Susan Einzig (from Germany), British book illustrator and art teacher

- Hedy Epstein (from Germany), American political activist

- Rose Evansky (from Germany), British hairdresser

- Walter Feit (from Austria), American mathematician

- John Grenville (from Germany), British historian

- Hanus J. Grosz (from Czechoslovakia), American psychiatrist & neurologist

- Karl W. Gruenberg (from Austria), British mathematician

- Heini Halberstam (from Czechoslovakia), British mathematician

- Geoffrey Hartman (from Germany), American literary critic

- Eva Hesse (from Germany), American artist

- Sir Peter Hirsch HonFRMS FRS (from Germany), British metallurgist

- David Hurst (from Germany), actor

- Otto Hutter (from Austria), British physiologist

- Robert L. Kahn (from Germany), American professor of German studies and poet

- Helmut Kallmann (from Germany), Canadian musicologist and librarian

- Walter Kaufmann (from Germany), Australian and German author

- Peter Kinley (from Vienna), born Peter Schwarz in 1926, British artist

- Walter Kohn (from Austria), American physicist and Nobel laureate

- Renata Laxova (from Czechoslovakia), American geneticist

- Gerda Mayer (from Czechoslovakia), British poet

- Frank Meisler (from Danzig), Israeli architect and sculptor

- Gustav Metzger (from Germany), artist and political activist resident in Britain and stateless by choice

- Isi Metzstein OBE (from Germany), British architect

- Ruth Morley, nee Birnholz (from Austria), American costume designer for film and theater, created the Annie Hall look

- Otto Newman (from Austria), British sociologist

- Arno Penzias (from Germany), American physicist and Nobel laureate

- Hella Pick CBE (from Austria), British journalist

- Sidney Pollard (from Austria), British economic and labour historian

- Sir Erich Reich (from Austria), British entrepreneur

- Karel Reisz (from Czechoslovakia), British film director

- Lily Renée Wilhelm (from Austria), American comic book pioneer[64] (graphic novelist, illustrator)[65]

- Wolfgang Rindler (from Austria), British/American physicist prominent in the field of general relativity

- Paul Ritter (from Czechoslovakia), architect, planner and author

- Michael Roemer (from Germany), film director, producer and writer

- Dr. Fred Rosner (from Germany), Professor of medicine and medical ethicist

- Joe Schlesinger, CM (from Czechoslovakia), Canadian journalist and author

- Hans Schwarz (from Austria), artist

- Lore Segal (from Austria), American novelist, translator, teacher, and author of children's books, whose adult book Other People's Houses describes her own knocked-from-house-to-house experiences

- Robert A. Shaw (b. Schlesinger, Vienna) British, professor of chemistry

- Dame Stephanie Steve Shirley CH, DBE, FREng (from Germany), British businesswoman and philanthropist

- Michael Steinberg, (from Breslau, Germany—now Wrocław, Poland), American music critic

- Sir Guenter Treitel QC FBA (from Germany), British law scholar

- Marion Walter (from Germany), American mathematics educator

- Hanuš Weber (from Czechoslovakia), Swedish TV producer

- Yitzchok Tuvia Weiss (from Czechoslovakia), Chief Rabbi of Jerusalem

- Peter Wegner (from Austria), American computer scientist.[66]

- Ruth Westheimer (born Karola Siegel, 1928; known as "Dr. Ruth") (from Germany), German-American sex therapist, talk show host, author, professor, and former Haganah sniper.[67][68][69]

- Herbert Wise (from Austria), British theatre and television director.[70]

- George Wolf (from Austria), American professor of physiological chemistry

- Astrid Zydower MBE (from Germany), British sculptor

Post-war organisations

[edit]In 1989, Bertha Leverton, who escaped Germany via Kindertransport, organised the Reunion of Kindertransport, a 50th-anniversary gathering of kindertransportees in London in June 1989. This was a first, with over 1,200 people, kindertransportees and their families, attending from all over the world. Several came from the east coast of the US and wondered whether they could organise something similar in the U.S. They founded the Kindertransport Association in 1991.[71]

The Kindertransport Association is a national American not-for-profit organisation whose goal is to unite these child Holocaust refugees and their descendants. The association shares their stories, honours those who made the Kindertransport possible, and supports charitable work that aids children in need. The Kindertransport Association declared 2 December 2013, the 75th anniversary of the day the first Kindertransport arrived in England, as World Kindertransport Day.

In the United Kingdom, the Association of Jewish Refugees houses a special interest group called the Kindertransport Organisation.[72]

The Kindertransport programme in media

[edit]Documentary films

[edit]- The Hostel (1990), a two-part BBC documentary, narrated by Andrew Sachs. It documented the lives of 25 people who fled the Nazi regime, 50 years on from when they met for the first time as children in 1939, at the Carlton Hotel in Manningham, Bradford.[73]

- My Knees Were Jumping: Remembering the Kindertransports (1996; released theatrically in 1998), narrated by Joanne Woodward.[74] It was nominated for the Grand Jury Prize at the Sundance Film Festival.[75] It was directed by Melissa Hacker, daughter of costume designer Ruth Morley, who was a Kindertransport child. Melissa Hacker has been influential in organizing the kinder who now live in America. She was also involved in working to arrange the award of 2,500 euros from the German Government to each of the kinder.

- Into the Arms of Strangers: Stories of the Kindertransport (2000), narrated by Judi Dench and winner of the 2001 Academy Award for best feature documentary. It was produced by Deborah Oppenheimer, daughter of a Kindertransport child,[76] and written and directed by three-time Oscar winner Mark Jonathan Harris. This film shows the Kindertransport in personal terms by presenting the actual stories through in-depth interviews with several individual kinder, rescuers Norbert Wollheim and Nicholas Winton, a foster mother who took in a child, a Dunera survivor and later British Army sergeant Abrascha Gorbulski and later Alexander Gordon, and a mother who lived to be reunited with daughter Lore Segal. It was shown in cinemas around the world, including in Britain, the United States, Austria, Germany, and Israel, at the United Nations, and on HBO and PBS. A companion book with the same title expands upon the film.

- The Children Who Cheated the Nazis (2000), a Channel 4 documentary film. It was narrated by Richard Attenborough, directed by Sue Read, and produced by Jim Goulding. Attenborough's parents were among those who responded to the appeal for families to foster the refugee children; they took in two girls.

- Nicky's Family (2011), a Czech documentary film. It includes an appearance by Nicholas Winton.

- The Essential Link: The Story of Wilfrid Israel (2017), an Israeli documentary film by Yonatan Nir. It proposes that Wilfrid Israel played a significant part in the initiation of the Kindertransport. Seven men and women from different countries and backgrounds tell the stories, of the days before and when they boarded the Kindertransport trains in Germany.

Feature films

[edit]- One Life, a 2023 British biographical drama film directed by James Hawes. It is based on the true story of British banker, stockbroker and humanitarian Nicholas Winton as he looks back and reminisces about his past involvement and efforts to help Jewish children in German-occupied Czechoslovakia to escape in 1938-39.

Plays

[edit]- Kindertransport: The Play (1993), a play by Diane Samuels. It examines the life, during the war and afterwards, of a Kindertransport child. It presents the confusions and traumas that arose for many kinder, before and after they were fully integrated into their British foster homes. And, as importantly, their confusion and trauma when their real parents reappeared in their lives; or more likely and tragically, when they learned that their real parents were dead. There is also a companion book by the same name.

- The End Of Everything Ever (2005), a play for children by the New International Encounter group, which follows the story of a child sent from Czechoslovakia to London by train.[77]

Books

[edit]- I Came Alone: the Stories of the Kindertransports (1990, The Book Guild Ltd) edited by Bertha Leverton and Shmuel Lowensohn, a collective non-fiction description by 180 of the children of their journey fleeing to England from December 1938 to September 1939 unaccompanied by their parents, to find refuge from Nazi persecution.

- And the Policeman Smiled: 10,000 children escape from Nazi Europe (1990, Bloomsbury Publishing) by Barry Turner, relates the tales of those who organised the Kindertransporte, the families who took them in and the experiences of the children.

- Austerlitz (2001), by the German-British novelist W. G. Sebald, is an odyssey of a Kindertransport boy brought up in a Welsh manse who later traces his origins to Prague and then goes back there. He finds someone who knew his mother, and he retraces his journey by train.

- Into the Arms of Strangers: Stories of the Kindertransport (2000, Bloomsbury Publishing), by Mark Jonathan Harris and Deborah Oppenheimer, with a preface by Richard Attenborough and historical introduction by David Cesarani. Companion book to the Oscar-winning documentary, Into the Arms of Strangers: Stories of the Kindertransport with expanded stories from the film and additional interviews not included in the film.

- Sisterland (2004), a young adult novel by Linda Newbery, concerns a Kindertransport child, Sarah Reubens, who is now a grandmother; 16-year-old Hilly uncovers the secret her grandmother has kept hidden for years. This novel was shortlisted for the 2003 Carnegie Medal.[78]

- My Family for the War (2013), a young adult novel by Anne C. Voorhoeve, recounts the story of Franziska Mangold, a 10-year-old Christian girl of Jewish ancestry who goes on the Kindertransport to live with an Orthodox British family.

- Far to Go (2012), a novel by Alison Pick, a Canadian writer and descendant of European Jews, is the story of a Sudetenland Jewish family who flee to Prague and use bribery to secure a place for their 6-year-old son aboard one of Nicholas Winton's transports.

- The English German Girl (2011), a novel by British writer Jake Wallis Simons, a fictional account of a 15-year-old Jewish girl from Berlin who is brought to England via the Kindertransport operation.

- The Children of Willesden Lane (2017), a historical novel for young adults by Mona Golabek and Lee Cohen, about the Kindertransport, told through the perspective of Lisa Jura, mother of Mona Golabek.

- The Last Train to London (2020), a fictionalised account of the activities of Geertruida Wijsmuller-Meijer by Meg Waite Clayton, also published in Dutch as De laatste trein naar de vrijheid.

- Escape from Berlin (2013), a novel by Irene N. Watts, is a fictional account of two Jewish girls, Marianne Kohn and Sophie Mandel, who fled Berlin through the Kindertransport.

Personal accounts

[edit]- Bob Rosner (2005) One of the Lucky Ones: rescued by the Kindertransport, Beth Shalom in Nottinghamshire. ISBN 0-9543001-9-X. -- An account of 9-year-old Robert from Vienna and his 13-year-old sister Renate, who stayed throughout the war with Leo Schultz in Hull and attended Kingston High School. Their parents survived the war and Renate returned to Vienna.

- Brand, Gisele. Comes the Dark. Verand Press, (2003). ISBN 1-876454-09-1. Published in Australia. A fictional account of the author's family life up to the beginning of the war, her experiences on the kinder-transport and life beyond.

- David, Ruth. Child of our Time: A Young Girl's Flight from the Holocaust, I.B. Tauris.

- Fox, Anne L., and Podietz, Eva Abraham. Ten Thousand Children: True stories told by children who escaped the Holocaust on the Kindertransport. Behrman House, Inc., (1999). ISBN 0-874-41648-5. Published in West Orange, New Jersey, United States of America.

- Golabek, Mona and Lee Cohen. The Children of Willesden Lane — account of a young Jewish pianist who escaped the Nazis by the Kindertransport.

- Edith Bown-Jacobowitz, (2014) "Memories and Reflections:a refugee's story", 154 p, by 11 point book antiqua (create space), Charleston, USA ISBN 978-1495336621, Bown went in 1939 with her brother Gerald on Kindertransport from Berlin to Belfast and to Millisle Farm (Northern Ireland) [more info|Wiener Library Catalogue Archived 23 December 2014 at the Wayback Machine

- Newman, Otto, British sociologist and author; Escapes and Adventures: A 20th Century Odyssey. Lulu Press, 2008.

- Oppenheimer, Deborah and Harris, Mark Jonathan. Into the Arms of Strangers: Stories of the Kindertransport (2000, republished 2018, Bloomsbury/St Martins, New York & London) ISBN 1-58234-101-X.

- Segal, Lore. Other People's Houses – the author's life as a Kindertransport girl from Vienna, told in the voice of a child. The New Press, New York 1994.

- Smith, Lyn. Remembering: Voices of the Holocaust. Ebury Press, Great Britain, 2005, Carroll & Graf Publishers, New York, 2006. ISBN 0-7867-1640-1.

- Strasser, Charles. From Refugee to OBE. Keller Publishing, 2007, ISBN 978-1-934002-03-2.

- Weber, Hanuš. Ilse: A Love Story Without a Happy Ending, Stockholm: Författares Bokmaskin, 2004. Weber was a Czech Jew whose parents placed him on the last Kindertransport from Prague in June 1939. His book is mostly about his mother, who was killed in Auschwitz in 1944.

- Whiteman, Dorit. The Uprooted: A Hitler Legacy: Voices of Those Who Escaped Before the "Final Solution" by Perseus Books, Cambridge, MA 1993.

- A collection of personal accounts can be found at the website of the Quakers in Britain at www.quaker.org.uk/kinder.

- Leverton, Bertha and Lowensohn, Shmuel (editors), I Came Alone: The Stories of the Kindertransports, The Book Guild, Ltd., 1990. ISBN 0-86332-566-1.

- Shirley, Dame Stephanie,Let IT Go: The Memoirs of Dame Stephanie Shirley. After her arrival in the UK as a five-year-old Kindertransport refugee, she went on to make a fortune in with her software company; much of which she gave away.

- Frieda Stolzberg Korobkin (2012). Throw Your Feet Over Your Shoulders: Beyond the Kindertransport (a first-hand account of a child of the Kindertransport from Vienna, Austria ). Dorrance. ISBN 978-1434930712.

- Part of The Family – The Christadelphians and the Kindertransport, a collection of personal accounts of Kindertransport children sponsored by Christadelphian families. Part of the Family

Winton train

[edit]On 1 September 2009, a special Winton train set off from the Prague Main railway station. The train, consisting of an original locomotive and carriages used in the 1930s, headed to London via the original Kindertransport route. On board the train were several surviving Winton children and their descendants, who were to be welcomed by the then hundred-year-old Sir Nicholas Winton in London. The occasion marked the 70th anniversary of the intended last Kindertransport, which was due to set off on 3 September 1939 but did not because of the outbreak of the war. At the train's departure, Sir Nicholas Winton's statue was unveiled at the railway station.[79]

Controversy

[edit]Jessica Reinisch notes how the British media and politicians alike allude to the Kindertransport in contemporary debates on refugee and migration crises. She argues that "the Kindertransport" is used as evidence of Britain's "proud tradition" of taking in refugees; but that such allusions are problematic as the Kinderstransport model is taken out of context and thus subject to nostalgia. She points out that countries such as Britain and the United States did much to prevent immigration by turning desperate people away; at the Évian Conference in 1938, participant nations failed to reach agreement about accepting Jewish refugees who were fleeing Nazi Germany.[80]

See also

[edit]- Jews escaping from Nazi Europe to Britain

- Bunce Court School, Otterden, Kent

- Elpis Lodge

- Hansi Neumann flight

- Leica Freedom Train

- Hanna Bergas – one of three teachers to help children arriving at Dovercourt

- Anna Essinger – set up the reception camp at Dovercourt

- Else Hirsch – helped organise ten Kindertransports

- Chiune Sugihara – some 300 Jewish children are estimated to have been saved through his efforts

- Norbert Wollheim – Jewish youth movement leader in Berlin, organised Kindertransports from Berlin

- Œuvre de secours aux enfants

References

[edit]- ^ Levy, Mike (2023). Get the Children Out! Unsung heroes of the Kindertransport. Lemon Soul, UK. p. 268. ISBN 978-1-999378141.

- ^ "Kindertransport". History Learning Site. July 2009. Retrieved 29 March 2019.

- ^ a b "Kindertransport; Organising and Rescue". The National Holocaust Centre and Museum. 12 December 2016. Retrieved 29 March 2019.

- ^ Mark, Jonathan (5 December 2018). "The Long Goodbye: Kindertransport Revisited 80 Years After". Jewish Week.

- ^ Thompson, Simon (20 December 2018). "Kindertransport survivor sees German payments as history acknowledged". Reuters.

- ^ Marcia W. Posner (2014). Zachor: Not Only to Remember; The Holocaust Memorial and Tolerance Center of Nassau County... Its First Twenty Years

- ^ a b "600 Child Refugees Taken From Vienna; 100 Jewish Youngsters Going to Netherlands, 500 to England". The New York Times. 6 December 1938. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 29 March 2019.

- ^ "Remembering the Kindertransport: 80 Years on". The Jewish Museum London. 26 October 2018.

- ^ Holtman, Tasha (2014). ""A Covert from the Tempest": Responsibility, Love and Politics in Britain's "Kindertransport"". The History Teacher. 48 (1): 107–126. JSTOR 43264384.

- ^ Holmes, Rose (2013). "A Moral Business: British Quaker Work with Refugees from Fascism,, 1933-1939". University of Sussex. p. 130. Retrieved 10 October 2024.

- ^ "Kindertransport, 1938–1940". encyclopedia.ushmm.org. Retrieved 29 March 2019.

- ^ a b "Racial, Religious and Political Minorities. (Hansard, 21 November 1938)". Parliamentary Debates (Hansard). 21 November 1938.

- ^ "RACIAL, RELIGIOUS AND POLITICAL MINORITIES. (Hansard, 21 November 1938)". Parliamentary Debates (Hansard). 21 November 1938.

- ^ Tenembaum, Baruch. "Nicholas Winton, British savior". The International Raoul Wallenberg Foundation. Retrieved 3 September 2009.

- ^ a b "Kindertransport, Jewish children leave Prague – Collections Search – United States Holocaust Memorial Museum". collections.ushmm.org. Retrieved 29 March 2019.

- ^ a b "Kindertransport | About Us | World Jewish Relief Charity". www.worldjewishrelief.org. Retrieved 29 March 2019.

- ^ "Kindertransport". Holocaust Website. East Renfrewshire Council. Archived from the original on 21 October 2006.

- ^ Oppenheimer. Into the Arms of Strangers. p. 98.

- ^ Oppenheimer. Into the Arms of Strangers. p. 76.

- ^ 1939 [SIC] England: Children Arrive Harwich off Ship Prague (Motion picture). 1938. Retrieved 8 March 2021.

- ^ a b Williams, Amy (January 2020). Memory of the Kindertransport in National and Transnational Perspective (Doctor of Philosophy). Nottingham Trent University.

At 5.30 AM on 2 December 1938 the SS Prague docked at Parkeston Quay. On board were 196 children, the first arrivals of what would become known as the 'Kindertransport'... None were accompanied by their parents.

- ^ World Jewish Relief

- ^ Wasserstein, Bernard (2014). The Ambiguity of Virtue: Gertrude van Tijn and the Fate of the Dutch Jews. Harvard University Press. pp. 50–52. ISBN 9780674281387. OCLC 861478330.

- ^ Rudberg, Pontus (2017). The Swedish Jews and the Holocaust. Routledge. pp. 114–117, 131–137. ISBN 9781138045880. OCLC 1004765246.

- ^ a b Kushner, Tony (2012). "Constructing (another) ideal refugee journey: the kinder". The battle of Britishness: Migrant journeys, 1685 to the present. Manchester University Press. p. 134. ISBN 978-0-7190-6641-2.

- ^ "The Winton Children: The roles of Trevor Chadwick and Bill Barazetti" (PDF). Association of Jewish Refugees. 11: 5. August 2011.

- ^ Keesing, Miriam (21 August 2010). "The children of tante Truus". het Parool. Retrieved 28 January 2015.

- ^ a b "Kindertransport and KTA History". The Kindertransport Association. Archived from the original on 4 November 2012. Retrieved 2 February 2014.

- ^ Lucy Dawidowicz (1986), The War Against the Jews. New York, Bantam Books. ISBN 0-553-34302-5.

- ^ Documenting Numbers of Victims of the Holocaust and Nazi Persecution. Encyclopedia.ushmm.org. Retrieved 2019-01-29

- ^ Conference, Claims (17 December 2018). "80th Anniversary of Kindertransport Marked with Compensation Payment to Survivors". Claims Conference. Retrieved 29 March 2019.

- ^ "Kindertransport Sculpture". Imperial War Museum collections. Retrieved 9 November 2016.

- ^ Fieldsend, John (2014). A Wondering Jew. Radec Press. p. 29. ISBN 978-0-9929094-0-6.

- ^ Holocaust Map (2024). "Broadreeds Holiday Camp, Selsey-on-Sea". The Association of Jewish Refugees (AJR) and the UK Holocaust Memorial Foundation. Retrieved 29 June 2024.

- ^ "Bremen Passenger Lists (the Original)". Bremen Chamber of Commerce and the Bremen Staatsarchiv. Retrieved 2 February 2014.

- ^ "JEWISH CHILD REFUGEES REACH ENGLAND – FIRST CONTINGENT FROM GERMANY". The Daily Telegraph. London. 3 December 1938. pp. 14 to 16.

- ^ "The Times". London. 12 December 1938. p. 13.

- ^ "Quakers in Action: Kinder-transport". Quakers in the World. Retrieved 2 February 2014.

- ^ "Kindertransport". Quakers in Britain. Archived from the original on 3 February 2014. Retrieved 2 February 2014.

- ^ Holmes, Rose (June 2011). "British Quakers and the rescue of Jewish refugees". Journal of the Association of Jewish Refugees. Retrieved 2 February 2014.

- ^ Bramsted, Eric. "A tribute to Bertha Bracey". Quakers in Britain. Archived from the original on 3 February 2014. Retrieved 2 February 2014.

- ^ Klinger, Jerry (21 August 2010). "Beyond Balfour". Christian In Israel. The Jerusalem Post. Retrieved 30 May 2013.

- ^ a b c Hasson, Nir; Lahav, Yehuda (2 September 2009). "Jews saved by U.K. stockbroker to reenact 1939 journey to safety". Haaretz. Retrieved 2 February 2014.

- ^ He was born into a Jewish family in Danzig (now Gdańsk, Poland), and was evacuated by the Kindertransport in August 1939, travelling with other Jewish children via Berlin to the Netherlands and then to Liverpool Street station in London.

- ^ Craig A. Spiegel: Returning 'home' after fleeing on the Kindertransport. In: Cleveland Jewish News. 14. August 2009.

- ^ "Kindertransport statue to mark WWII refugees' arrival in Harwich". BBC News. 1 September 2022. Retrieved 27 February 2023.

- ^ Cohen, Melvin (1999). Habonim in Britain 1929-1955. Israel: Irgun Vatikei Habonim. pp. 155, 196–203.

- ^ Golabeck, Mona; Cohen, Lee (2002). Children of Willesden Lane: Beyond the Kindertransport: A Memoir of Music, Love, and Survival. New York: Warner Books. ISBN 0446527815. LCCN 2002100990.

- ^ "ČD Winton Train – Biography". Winton Train. České drahy. 2009. Archived from the original on 9 September 2009. Retrieved 3 September 2009.

- ^ "Nicholas Winton, the Schindler of Britain". www.auschwitz.dk. Louis Bülow. 2008. Archived from the original on 7 February 2014. Retrieved 3 September 2009.

- ^ "UK's 'Schindler' awaits Nobel vote". BBC News. 1 February 2008. Retrieved 2 February 2014.

- ^ Emanuel, Muriel; Gissing, Věra (2002). Nicholas Winton and the rescued generation : save one life, save the world. London: Vallentine Mitchell. ISBN 0853034257. LCCN 2001051218.

Many German refugee boys and some Winton children were given refuge in Christadelphian homes and hostels and there is substantial documentation to show how closely Overton worked with Winton and, later, with Winton's mother.

- ^ Brade, Laura E.; Holmes, Rose (2017). "Troublesome Sainthood: Nicholas Winton and the Contested History of Child Rescue in Prague, 1938-1940". History and Memory. 29 (1): 11–22. doi:10.2979/histmemo.29.1.0003. JSTOR 10.2979/histmemo.29.1.0003. S2CID 159631013.

- ^ Brade and Holmes 2017, pp. 23–29.

- ^ Brade and Holmes 2017, pp. 5–6.

- ^ Brade, Laura E. (2017). "Networks of Escape: Jewish Flight from the Bohemian Lands, 1938-1941". Carolina Digital Depository. University of North Carolina. pp. iii, iv. Retrieved 10 October 2024.

- ^ Naomi Shepherd: A Refuge from Darkness Pantheon books, New York, 1984. Published as Wilfrid Israel, German Jewry's Secret Ambassador by Weidenfeld and Nicolson, London, in 1984; in German translation by Siedler Verlag, Berlin; and in Hebrew as שגריר ללא ארץ, the Bialik Institute in 1989. This biography won the Wingate Prize for the best book on Jewish subjects for 1984.

- ^ See the entry Solomon Schonfeld, and the book Holocaust Hero: Solomon Schonfeld, by Dr. Kranzler (Ktav Publishing House, New Jersey, 2004).

- ^ a b "Collar the Lot," by Peter and Leni Gillman, Quartet Books Limited, London (1980)

- ^ "Striking Back" by Peter Masters, Presideo Press, CA (1997)

- ^ Wyman, David S. (1984). The Abandonment of the Jews: America and the Holocaust 1941–1945. New York: Pantheon Books. pp. 124–142. ISBN 0-394-42813-7.

- ^ "How many refugees came to the United States from 1933 to 1945". U.S. Holocaust Memorial Museum. Retrieved 10 August 2023.

- ^ Gurock, Jeffrey (Editor). America, American Jews, and the Holocaust: American Jewish History. Taylor & Francis, 1998, ISBN 0415919312, p.227

- ^ "Lily Renee, Escape Artist: From Holocaust Survivor to Comic Book Pioneer". Indie Bound. American Booksellers Association. Retrieved 9 January 2013.

- ^ Robbins, Trina (2011). Lily Renee, escape artist: from Holocaust survivor to comic book pioneer. London: Graphic Universe. ISBN 9780761381143.

- ^ "Peter Wegner: A Life Remarkable". 31 May 2016.

- ^ Fabulous Finds; How Expert Appraiser Lee Drexler Sold Wall Street's "Charging Bull," Found Hidden Treasures and Mingled with the Rich & Famous

- ^ Hoffman, Jordan (17 December 2021). "Tovah Feldshuh is very becoming in 'Becoming Dr. Ruth'". Times of Israel.

- ^ "Sex therapist, researcher Dr. Ruth given honorary doctorate by BGU; Born in Germany into a religious Jewish household in 1928, Dr. Ruth Westheimer was sent to Switzerland on the Kindertransport at age 10. Her parents were murdered in the Holocaust.," The Jerusalem Post, April 28, 2021.

- ^ Holmes, Mannie (14 August 2015). "Herbert Wise, 'I, Claudius' Director, Dies at 90". Variety.

- ^ "Kindertransport and KTA History: Kaddish in London". The Kindertransport Association. Archived from the original on 9 May 2016. Retrieved 2 February 2014.

- ^ "Kindertransport". www.ajr.org.uk.

- ^ "News Weather followed by The Hostel – BBC One London – 5 July 1990 – BBC Genome". The Radio Times (3472): 54. 28 June 1990. Retrieved 10 October 2018.

- ^ "League of Professional Theatre Women biography". Archived from the original on 5 August 2009.

- ^ "My Knees Were Jumping: Remembering the Kindertransports" – via IMDb.

- ^ "Deborah Oppenheimer: Biography | The Kindertransport". Bloomsbury USA. Archived from the original on 1 March 2009. Retrieved 2 February 2014.

- ^ "The End Of Everything Ever". New International Encounter. Archived from the original on 21 May 2014. Retrieved 20 May 2014.

- ^ "Books News: Carnegie Medal 2003". Guardian. Retrieved 2 February 2014.

- ^ ČTK (1 September 2009). "Train in honour of Jewish children rescuer Winton leaves Prague". České noviny. Neris s.r.o. Archived from the original on 4 September 2009. Retrieved 1 September 2009.

- ^ Reinisch, Jessica (29 September 2015). "History matters... but which one? Every refugee crisis has a context". History & Policy. Retrieved 5 July 2015.

- ^ Whilst this was somewhat of an exaggeration – it was traumatic for the parents to send their children away into the "unknown" and for an uncertain time; and traumatic for at least the younger children to be separated from their parents – the actual parting was managed well.

Further reading

[edit]- Baumel-Schwartz, Judith Tydor (2012). Never Look Back: The Jewish Refugee Children in Great Britain, 1938–1945. West Lafayette, Indiana: Purdue University Press. ISBN 978-1-557-53612-9.

- Turner, Barry (1990). And the Policeman Smiled. London: Bloomsbury Publishing PLC. ISBN 0747506205.

- Abel Smith, Edward (2017), "Active Goodness – The True Story of How Trevor Chadwick, Doreen Warriner & Nicholas Winton Saved Thousands From The Nazis", Kwill Publishing, ISBN 978-8-49475-485-2

- Mann, Jessica (2005). Out of Harm's Way. St Ives: Headline Book Publishing. ISBN 0-7553-1138-8.

- Craig-Norton, Jennifer (2019). The Kindertransport: Contesting Memory. Bloomington: Indiana University Press. ISBN 978-0-253-04222-4.

- Levy, Mike (2023). Get the Children Out! Unsung heroes of the Kindertransport. Lemon Soul, UK. p. 268. ISBN 978-1-999378141.

External links

[edit]- The Kindertransport Association – Organisation for Kinder and their families in the United States

- Educational site focusing on the children arriving in Britain

- About World Jewish Relief's (formerly the Central British Fund) role in Kindertransport

- The Kindertransport Webpage maintained by the Association of Jewish Refugees in London, UK, with links to the Kindertransport Association of the United Kingdom.

- A collection of personal reminiscences and tributes from people who were rescued on the Kindertransport, collected by the Quakers in 2008.

- Accounts of the Quaker contribution to Kindertransport on the Search and Unite website

- Link to information about the film "My Knees Were Jumping: Remembering the Kindertransports" (1996)

- Link to information about the film "Into the Arms of Strangers: Stories of the Kindertransport" (2000)

- Link to free downloadable companion study guide for "Into the Arms of Strangers: Stories of the Kindertransport" (2000)

- Link to information about the British documentary "The Children Who Cheated the Nazis" (2000)

- World Jewish Relief (formally known as The Central British Fund for German Jewry)

- Wiener Library in London (holds documents, books, pamphlets, video interviews on the Kindertransport)

- Archive of ten refugees in Gloucester in 1939[permanent dead link]

- Through My Eyes website (personal stories of war & identity – including 3 Kindertransport evacuees – an Imperial War Museum online resource)

- The Kindertransport Memory Quilt Exhibit at the Michigan Holocaust Center

- Interview with Ester Golan Archived 14 June 2017 at the Wayback Machine

- Kindertransport Memorial Collection at the Leo Baeck Institute Archives, New York, New York.

- Refugee children in the Netherlands

- Jewish Virtual Library article

- The Kindertransport to Great Britain - Stories from North Rhine-Westphalia (documentation by the Kindertransport Project Group of the Yavneh Memorial and Educational Centre, Cologne, Germany)

- Children depart 5.13 pm - Recollections of the Polenaktion and the Kindertransports of 1938/39 (online presentation commemorating the deportation of 17,000 Jewish people in the so-called Polenaktion as well as the rescue efforts known as Kindertransports)

- Kindertransport

- Children in war

- 1938 in the United Kingdom

- 1939 in the United Kingdom

- 1938 in Germany

- 1939 in Germany

- International response to the Holocaust

- The Holocaust and the United Kingdom

- Jews who immigrated to the United Kingdom to escape Nazism

- Jewish emigration from Nazi Germany

- Rescue of Jews during the Holocaust